There is a panoply of agencies regulating energy at the Commonwealth level and not all of these seem to be rowing in the same direction. The main agencies are

- The Energy and Environment Department with 490 staff in energy and greenhouse — plus another 454 in its dependent agencies: Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the Clean Energy Regulator and the Climate Change Authority;

- The Australian Energy Regulator (AER) with 283 staff;

- The Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC) with 95 staff;

- The Energy Security Board (ESB) with perhaps 10 staff; and

- The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) with 670 staff.

Although AEMO is mainly concerned with operational issues, its CEO and a good many of its resources are heavily involved in regulatory matters. Moreover, energy/environment policy is important for other agencies including Agriculture, Industry, Treasury, the ACCC and PM&C. The CSIRO and several other research agencies have considerable resources addressing it, while there are bodies like the Global Carbon Capture Initiative, largely Australian government-funded.

All in all, there are well in excess of 1500 people spread across a dozen federal different agencies involved in energy/greenhouse policy area. With such heavy government engagement, it is to be expected that the sector has been outstanding in terms of its deteriorating efficiency and increased costs. At the very least, the area ripe for the sort of rationalisation that is being undertaken with the government departments.

This week, the AEMC delivered its annual forecasts of household prices and costs covering the next three years. The Government would be welcoming its estimate that prices will rise little in 2019/20 and fall six per cent next year. One cause is suppressed demand induced by wholesale prices that have more than doubled since the subsidised renewables plague caused the 2017 closure of Hazelwood. Also, the sheer size of the subsidy-induced increase in renewable supplies has tended to reduce forward prices; the surge in new supplies has even dented the level of subsidy that these receive.

This replacement of reliable coal by intermittent wind and solar leaves the regulatory agencies on edge each year. This week AEMO, while extolling the benefits of more solar and wind supplies for the coming year, also announced that it had spent $40 million on insurance contracts for supplies and demand reductions that might not have been otherwise available. AEMO is pressing strongly for consumers being forced to fund additional transmission spending to facilitate the increased penetration of wind and solar and more spending on batteries/Snowy 2 to offset their unreliability.

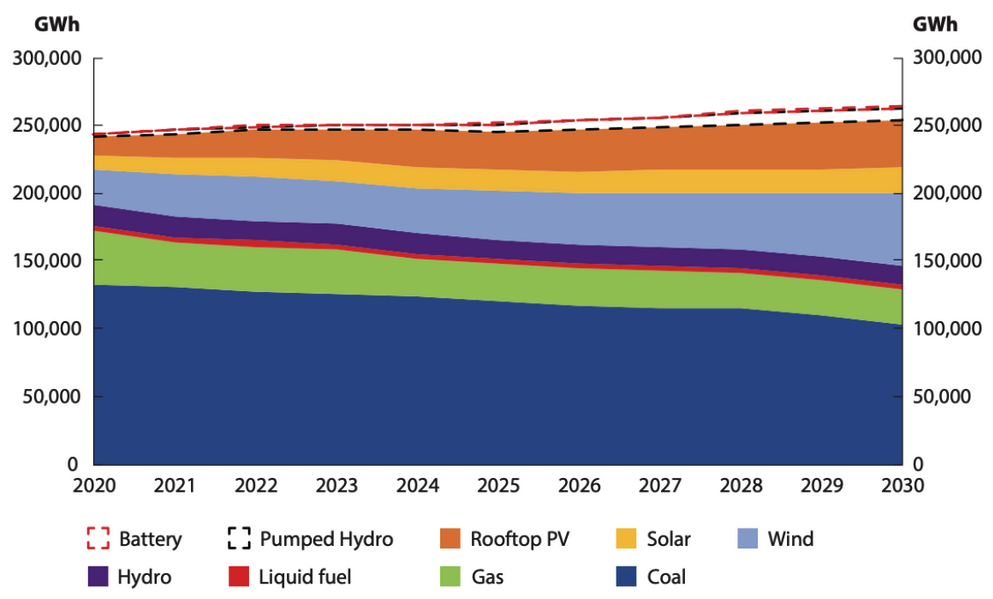

And just in case anyone was thinking that the AEMC’s estimated near–term fall in prices was the harbinger of a turnaround, also this week the Energy and Environment Department published its forecast of greenhouse gas emissions into the future. This has renewables supplying half of the electricity supply by 2030. At 40 per cent for wind/solar, this is double their 2020 projected share.

With wind/solar requiring at least $100 per MWh to be profitable (compared with coal at under $50), this means the upward trajectory must resume after the market has digested this year’s temporary glut.

The Department’s forward projections leave Australia at a crunch point because, even though cost-competitive renewables have been heralded for decades, the mirage constantly retreats. Hence, either a new set of regulatory assistance to renewables must be introduced or Australia reneges on its Paris Agreement “commitments”.

The latter approach would not only allow a convalescence and recovery of the battered energy industries but would also provide welcome relief for the agricultural sector. The heavy lifting envisaged to allow Australia to meet its 2030 goals is the prevention of land clearing — which also entails suppression of output. In net terms, this is responsible for all Australia’s emission reductions envisaged between 2005 and 2020.

The dilemma for Australian governments is either to seek prosperity or please “world opinion”, green radicals and doctors’ wives by taking further steps to undermine the economy’s productivity. Those of us concerned about future living standards have to hope that the Trumpian rejection of Paris brings about its abandonment giving scope for the government to revert to the policies that prevailed before climate concerns became the vogue.

lan Moran is with Regulation Economics.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in