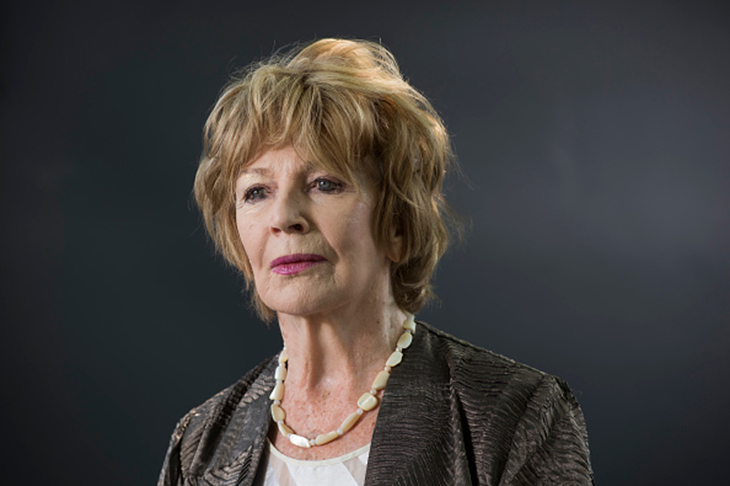

This novel is strikingly brave in two ways: first, in the fortitude of its writer, the redoubtable Edna O’Brien, who, aged 88, travelled twice to northern Nigeria, her bra stuffed with thousands of dollars, in order to research this story. With some irony, she ended up staying in a convent with kindly nuns who helped introduce her to its subject: the girls kidnapped by Boko Haram in 2014.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in