A prominent economist has written that capitalism is in crisis. Its wealth creation engine is sputtering. Those at the head of our large corporations have lost their bearings. Their entrepreneurial instincts are dulled, leaving them little more than bureaucrats. Their preparedness to defend the market system is diminished. As capitalism stumbles both economically and culturally, its critics, in academia and elsewhere, gain confidence. Long-harboured plans for radical change are unveiled. A normally sceptical public pays fresh attention to these views.

This economist was not writing today, but in 1943. His name is Joseph Schumpeter, one of the towering figures of 20th century economics. No one could fail to see the parallels between Schumpeter’s 1943 vision (in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy) and today’s developments.

Schumpeter argued that capitalism would be judged on its economic results; its capacity to foster innovation and technological change, economic growth and rising living standards. He did not take this for granted. Indeed, he speculated about ‘a more or less stationary state’, where capitalism would atrophy and there would be ‘nothing for entrepreneurs to do.’ In these circumstances, ‘profits and the rate of interest would converge toward zero’, reducing the management of industry to ‘current administration’. Its personnel would ‘acquire the characterisation of a bureaucracy’. Sound familiar?

Even if growth were to continue, investment, innovation and management were being routinised in large corporations, Schumpeter observed. Where once flesh-and-blood capitalists had occupied the commanding heights of business, by the 1940s they had been replaced by business executives who, Schumpeter felt, lacked an instinctive allegiance to capitalism and the values which underpinned it: private property, freedom of contract, the family unit, individual responsibility. Small shareholders would be no better, their detached interest in returns putting them at one remove to how wealth was created in the first place. Neither group, Schumpeter felt, were willing to defend capitalism from its hostile critics. Indeed, the business elite would seek to appease them, even adopting some of their arguments and proposals.

With the economy faltering and big business neutered, Schumpeter argued, capitalism’s critics would have the opening they needed. The campaign would be led by the intellectual class, a loose collection of people who, in Schumpeter’s words, ‘wield the power of the written and spoken word’, but lack ‘direct responsibility for practical affairs’. People who could, to put it crudely, talk about anything but who knew very little.

The irony was that capitalism, by subsidising the vigorous expansion of higher education, created and added numbers to this hostile group. As he put it, the unemployed, underemployed or unemployable graduates enter adulthood in a ‘thoroughly discontented frame of mind’, which rationalises itself into social criticism. An attitude of ‘righteous indignation about the wrongs of capitalism’ that brooks no rational argument.

Today, the radical critics of capitalism no longer march under the banner of socialism. As we all know, they preach from other gospels. Deep green environmentalism and the outer fringes of identity politics come to mind. Each, in different ways, advocates a state-led transformation of our way of life. And again, the dynamic discerned by Schumpeter is repeated today, with the intellectual class popularising formerly fringe views to the point where they gain political traction and a business elite too afraid (or lacking the instinct) to defend the existing order.

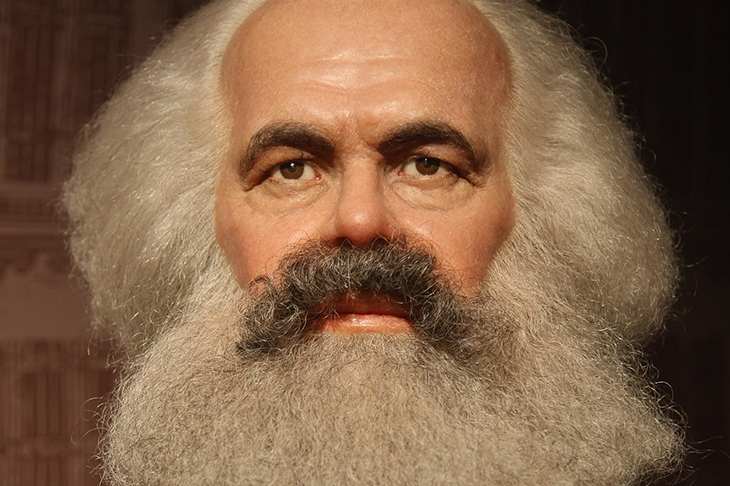

Why point to the parallels between today and 1943? Schumpeter did not confine himself to description, but argued the developments he highlighted portended no less than the end of capitalism. Not in the sudden, disruptive way fancifully described by Marx, but gradually, almost imperceptibly. And accompanied by a creeping consensus among elites, in both public and private sectors, that only through evermore pervasive planning and regulation could a higher level of civilisation be attained. Is Schumpeter’s prophecy finally coming to pass? In truth, there are many possible futures laid out for us. Nothing is inevitable or pre-determined, despite what hucksters always say.

Nevertheless, if we start with the capitalist economy, I do not see a permanent drying up of investment opportunities or loss of dynamism. Indeed, as many have pointed out, we are only now entering a fourth technological revolution. The low-growth, low-investment rut we are seeing globally is not due to strictly economic causes and nor will it be permanent. Regardless of the culprit, it is true that the longer recovery is delayed, the more discontent will fester as we saw in the 1930s.

Will the business elite see the error of their ways? If they can no longer bring themselves to defend private property and freedom of contract, others have stepped into the breach. Small businesses, new economy entrepreneurs, independent contractors and tradespeople have a genuine attachment to these values and are prepared to defend them. If white- collar employees have been bureaucratised, capitalism’s strongest allies are former members of the working class, as Paul Keating and Bob Hawke recognised.

And what of the anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois radicals? Yes, these have gained in influence over the past decade, but have overplayed their hand. They have mistaken the public’s preparedness to accept some of what they want (within the bounds of moderation) for an invitation to go the whole way. As a result, they have run ahead of public opinion, losing both support and traction. While elites have remained loyal, the same cannot be said for the broader community.

As an elitist himself, Schumpeter discounted the wider public’s capacity to shape events. Yet no-one familiar with recent Western political history can make that mistake. Something clearly is afoot. For the more excitable elites, it appears to be a collapse in trust or even an end to civilisation. It certainly has some confronting features. But perhaps, just perhaps, it is a reformation of sorts. A reconnection with formerly unfashionable bourgeois values, and, yes, the economic system they support.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in