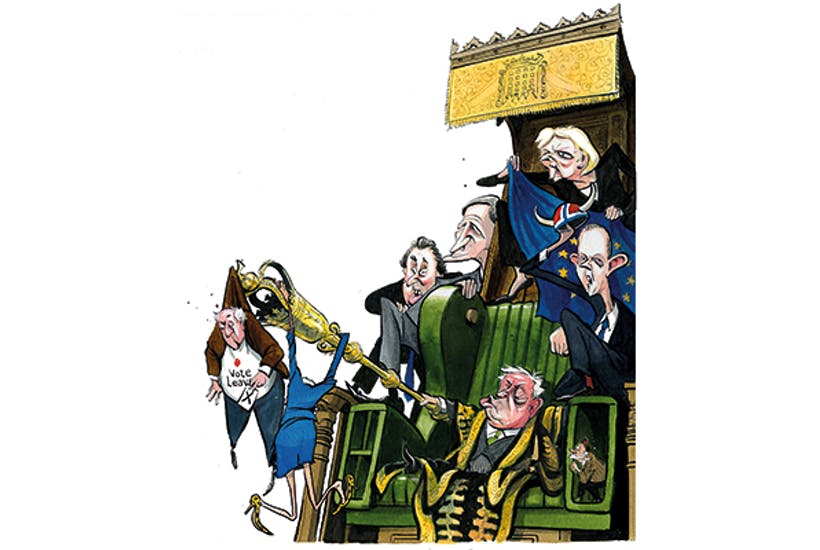

Since the referendum we have seen a steady escalation of the battle between the Commons and the government over Brexit. It will reach new heights in the run up to October 31st – as the new prime minister seeks to negotiate with the EU and maintain his room for manoeuvre by keeping no deal on the table, and those ardently opposed to no deal find more and more creative ways to stop it from happening. The question is: who will win?

Much depends on the way the Commons seeks to prevent no deal, the options available to the prime minister in responding, and crucially, the political cost associated with each option. Backbenchers seeking to wrest control of the Brexit process will try to paint any move they make as justified – no matter how destructive it is, or if it cuts off spending for schools, pensioners, and those reliant on benefits – and the prime minister’s moves as pure villainy. If they can win the air war in support of a particular tactic, persuading the media, their fellow MPs and the public they are right, MPs will hope to increase the perceived political cost of any counter-action a PM may take. We’ve already seen this game play out with prorogation, admittedly a nuclear option.

The battle will therefore not just be procedural but for control of the airwaves. Can the new No. 10 operation respond robustly and quickly? They’ll need a plan for different scenarios and how to handle them.

As has been said many times before, there is no legal requirement to seek the approval of MPs in a no-deal scenario. Stephen Barclay, Secretary of State for Exiting the EU, has also confirmed that for a no-deal Brexit, no further legislation is needed before exit day. This deprives MPs of a key vehicle to bind the PM’s hands – instead they must find other, more creative ways to stop no deal.

Firstly, MPs could seek to pass a motion condemning leaving without a deal, with the threat of holding the government in contempt if it proceeded. This was the device that was politically compelling enough to force Theresa May to publish the Attorney General’s legal advice in December 2018. It is likely that MPs will attempt to persuade the Speaker to allocate an Emergency Debate on the subject, and extraordinarily, and against all convention, allow the motion to be amended so it expresses a forceful opinion. While the motion would not be binding, if ignored the Speaker could permit a further motion finding ministers to be in contempt of parliament. If passed, and if no remedial action was taken by the government, ministers could be suspended from the House of Commons. A prime minister will need to examine the terms of the contempt motion, what response they can make, and how politically tolerable the situation is.

Secondly, MPs could try to legislate. They may persuade the Speaker to use the same Emergency Debate device to allow a motion that sets aside time for legislation. This was the tactic used by Yvette Cooper and Oliver Letwin earlier in the year to pass the EU Withdrawal Act 2019, which placed a duty on the PM to negotiate an extension. That piece of legislation received Royal Assent within four sitting days. But, an adept government could delay the passage of future legislation to buy time and would scrutinise it to see if there was any wiggle room if it passed.

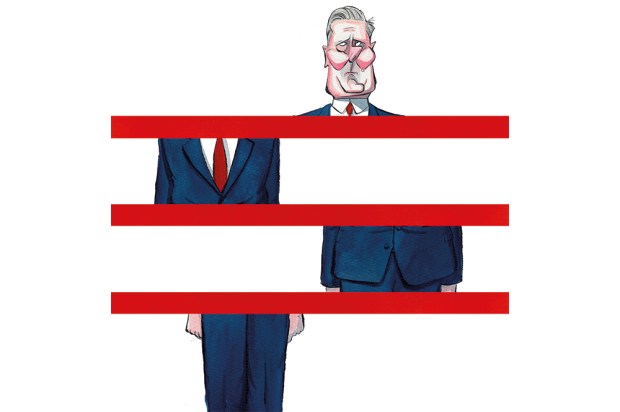

Thirdly, backbench MPs could pass a vote of no confidence in the government. By convention, the government will always promptly make time for such a vote, if the Leader of the Opposition (in this case, Jeremy Corbyn) has called for it. If the no-confidence vote passed, it would trigger a 14-day period for the government to regain the confidence of the House, or it would face a general election. The pressure on the prime minister to shift his position would be intense. However, as the prime minister would not be obliged to resign unless clear advice could be given to the Queen on who should be asked to form a government, he could simply wait for that period to expire and trust voters to re-elect him.

That’s why I expect that those planning to use this mechanism will also be thinking about how to form an alternative government and prove it can command a majority in that 14-day period. Here presenting the risks will be key. Is putting Corbyn into No. 10 (he is the only really viable option in terms of commanding sufficient Labour votes), and the price of a second referendum to win over the smaller parties worth it for backbench MPs?

All of this is in addition to the current fight, led by Dominic Grieve and Margaret Beckett, to deprive key public services of essential funding in a no-deal scenario.

With this Speaker, MPs have a wealth of options to prevent no deal, while the government is relatively limited. The clock will however be on the government’s side – if the next prime minister can head to the next EU Council summit on 17 October with his hands unbound, we may finally have the conditions for negotiations to shift.

But we may not find out what either Boris Johnson or Jeremy Hunt are planning just yet. To preserve what options the next prime minister will have, I think it would be wise for the Tory leadership candidates to avoid giving blow-by-blow examples of how they will respond to rebellious backbenchers, even if this does frustrate journalists hoping to find out their plans.

Nikki da Costa is senior counsel at Cicero and former director of legislative Affairs at Number 10.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in