Political violence is rare in Australia but a senior partner at a Sydney accounting firm gave a new ‘twist’ to chardonnay-socialism when he stabbed a Liberal party volunteer with a corkscrew, allegedly to further the cause of ‘real action’ on climate change. In China however, as Mao observed, political power grows out of the barrel of a gun, not a bottle opener. ‘According to the Marxist theory of the state, the army is the chief component of state power,’ he said in 1938. ‘Only with guns can the whole world be transformed.’ If you think that doesn’t inform the current Chinese leadership, you aren’t paying attention. On the 200th anniversary of the birth of Marx, President Xi Jinping said Marx’s theory ‘still shines with the brilliant light of truth.’

No-one is more conscious of this than the two million Hong Kongers who took to the city’s streets last Sunday to protest an extradition agreement put forward by their Chief Executive Carrie Lam, that would, for the first time, authorise extraditions to mainland China, not just for Hong Kong residents and Chinese nationals but for foreigners travelling through the city.

Why would almost one in three Hong Kongers turn out to protest? For starters, China has one of the most opaque and repressive judicial systems in the world, which criminalises freedom of speech, religion and movement and allows arbitrary arrest and detention, forced labour, torture and deprivation of life. All of this is par for the course in any tyrannical dictatorship. Where China moves into a realm occupied by few other despotic regimes is in turning the deaths of citizens into a money-making bonanza.

Since 2000, China has prioritised the organ transplantation industry in its Five-Year Plans. The sale of organs, to wealthy Chinese and foreign ‘transplant tourists’ is an extremely lucrative trade and as one Chinese paper put it, is ‘a mine of high-grade ore that can’t be exhausted.’ Human body parts are indeed the ultimate renewable resource but, in the West, they are in short supply — patients can wait years for an organ. Not in China, which claims that until 2015 the state sourced organs from executed common criminals and now claims all organs are sourced from ‘voluntary’ donors.

This week, an independent tribunal headed by Sir Geoffrey Nice, who led the prosecution of Slobodan Milosevic at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, found that despite China’s ‘pervasive culture of secrecy, silence and obfuscation’, the tribunal had come to the ‘unavoidable conclusion’ that organs are ‘harvested’, on demand, from prisoners of conscience. The evidence includes the extraordinarily short waiting times promised by hospitals, the massive scale of the transplant industry which commenced before any voluntary donor system was even mooted and the impossibility of there being anything like sufficient ‘donors’ under the voluntary scheme.

As for prisoners of conscience, there is no shortage. In 1999, General Secretary Jiang Zemin launched a brutal crackdown to ‘eliminate’ Falun Gong, a Buddhist-inspired practice which combines gentle exercise, meditation, and a philosophy of truthfulness, compassion and forbearance. At the time, it was the fastest-growing movement in China, with more adherents than the Chinese Communist Party’s 63 million members. The state branded it an ‘evil cult’ and rounded up hundreds of thousands of practitioners to be ‘re-educated’ in detention facilities. The China Tribunal found that Falun Gong practitioners are the main source of organ supply. China claims only 16,000 transplants are conducted a year but in 2017, a South Korean TV crew covertly filmed a transplant hospital in Tianjin where a nurse said the hospital performed three kidney and four liver transplants the previous day. If that was an average day, there would be 2,500 transplants a year just in that hospital and there are officially 169 transplant hospitals. The New York-based China Organ Harvest Research Centre estimated that the minimum national capacity was 70,000 transplants a year.

With so little transparency, it is difficult to calculate the value of the trade but with $US130,000 quoted for kidneys and $US 170,000 for a liver it is estimated to be worth billions. What is certain is that it is booming. In 2016, Huang Jiefu, China’s top transplant official, announced plans to increase transplant hospitals from 169 to 300 by 2020. Where will the extra organs come from? In the last year, the government forcibly detained hundreds of thousands of Muslims in ‘vocational skills education centres’ in Xinjiang. Human Rights Watch reported in 2017 that the government collected biological data from 19 million Uyghurs which the Tribunal fears may allow them to become an ‘organ bank.’ According to the Wall Street Journal, the police want to collect 100 million DNA samples nationwide by 2020.

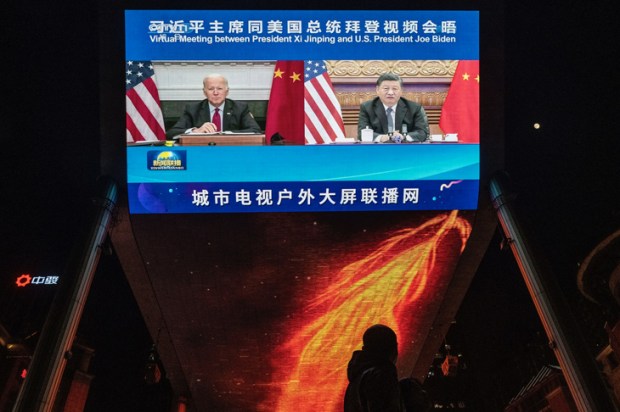

Against this backdrop, Hong Kong residents claim to have been framed for crimes they didn’t commit and arrested in China, Hong Kong and abroad. Little wonder they fear a formal extradition treaty. Yet despite the massive demonstrations, the international response has been muted. Taiwan’s prime minister said although Hong Kong’s demands for freedom seemed ‘to fall on deaf ears’, like-minded friends stand with them. No doubt, but few are prepared to risk compromising lucrative trade deals. Even President Trump who said he was impressed by the size of the rallies, perhaps comparing them with his inauguration turnout, confined himself to saying he hopes China and Hong Kong can ‘work it out’. This was more than Australia’s prime minister mustered, seemingly maintaining the ‘silence of the Lam’. Canberra’s ‘mandarins’ have always advocated turning a blind eye to Chinese human rights abuses and see any public criticism as ‘ideologically-driven China-bashing’ and a search for a new Cold War ‘bogeyman’, as one commentator dismissively put it.

Sydney University’s US Studies Centre launched a publication last week about how the US and Australia should respond to ‘a more externally aggressive and internally repressive China.’ In both countries, it said, ‘more public discussion is needed about the challenges associated with China’s rise,’ yet the Centre couldn’t even bring itself to name China in the report’s title, which it called rather obscurely, The Future of the US-Australia Alliance in an Era of Great Power Competition. No points for guessing why. China is the top source of international students in Australia — providing more than 150,000 last year, worth $11 billion, double student numbers from India, the second largest source, worth only $3.8 billion. With so much at stake, don’t expect the chardonnay socialists of academe, corkscrews in hand, to be storming China’s barricades any time soon.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in