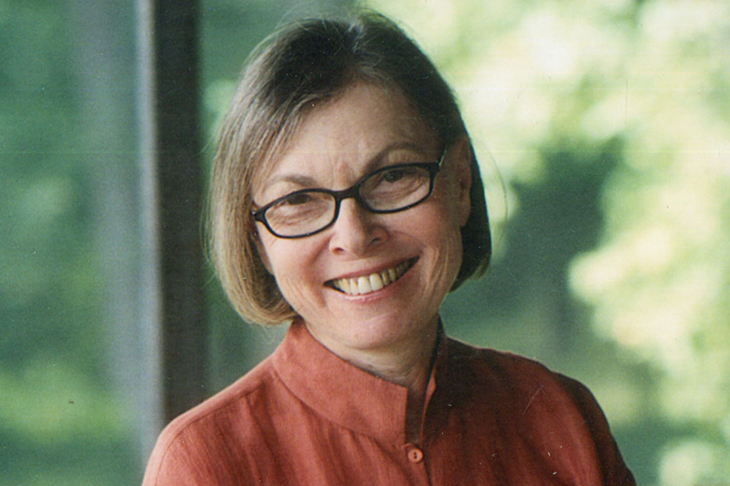

God, I wish I was Janet Malcolm. Fifty or more years as a staff writer on the New Yorker, reviews in the New York Review of Books, the occasional incendiary non-fiction bestseller (In the Freud Archives, The Journalist and the Murderer, The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes), even the famous lawsuit. (She was sued for libel by the psychoanalyst Jeffrey Masson.) If Janet Malcolm is the thinking woman’s Joan Didion, then Nobody’s Looking at You is her Slouching Towards Bethlehem: a lot less slouching.

Nobody’s Looking at You collects just over a dozen of Malcolm’s articles from the past decade or so, ranging from some pretty stringent profile pieces to a few rambling book reviews and feature articles. The range is impressive, if slightly humourless and bewildering, like flicking through an entire New Yorker without the light relief of the cartoons, the casuals, or Anthony Lane.

The book includes, for example, a thoughtful review of the nine-part cable channel docuseries Sarah Palin’s Alaska, a rather faded colour piece about the Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert Rally to Restore Sanity and/or Fear held in Washington in October 2010 — remember that? no — and two long articles about Tolstoy which show Malcolm off at her formidable, straight-talking best:

A sort of asteroid has hit the safe world of Russian literature in English translation.

A couple named Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky have established an industry of taking everything they can get their hands on written in Russian and putting it into flat, awkward English.

(Malcolm is good on the Russians: she seems instinctively to understand the endless soul-searching, the sentimentality and the high seriousness. Her short book on Chekhov is one of the best introductions there is to the life and work of the great, doomed, self-examining doctor.

Given her reputation, it’s amazing that anyone would offer themselves as a subject to Malcolm for a profile piece, but offer themselves they do and they have, just as people here used to line up to be viciously sheared by Lynn Barber. Vanity, masochism, arrogance? Who knows the motives of the rich and the famous? Certainly not the rich and the famous — and maybe not even Janet Malcolm, who often seems to come away from her interviews as puzzled by her subjects as they are. Maybe that’s the point. Maybe that’s the appeal.

In the piece ‘Performance Artist’, for example, Malcolm meets the pianist Yuja Wang and is clearly troubled by Wang’s appearance:

Extremely short and tight dresses that ride up as she plays, so that she has to tug at them when she has a free hand, or clinging backless gowns that give an impression of near-nakedness (accompanied in all cases by four-inch-high stiletto heels)… She looked like a dominatrix or a lion tamer’s assistant.

What does this mean for classical music? What are its implications? What does it tell us about the star system and the culture of celebrity? Malcolm asks all the right questions, offers some interesting answers, but finally concludes that Wang is just young, confused and kooky.

In the book’s title piece, Malcolm meets the fashion designer Eileen Fisher, who makes expensive clothes for smart American women. Malcolm calls the Fisher phenomenon ‘a kind of cult of the interestingly plain’. There’s a lot of trademark tugging and teasing that goes on here in the Fisher piece, as if Malcolm were testing a piece of fabric:

I noticed that whenever the workings of the company came under discussion the language became peculiar and contorted, as if something were being hidden. In fact, the company has nothing to hide.

But if all she did was pinprick, prod and poke, Malcolm would simply be unpleasant. Her other great skill is focusing on odd and unexpected details and offering them up as vague, conclusive metaphors. Thus, she concentrates on Fisher’s cat:

He was the bad cat. He had once lived in the house with the other cats, but he had fought with the second male cat and peed all over the floor and when the housekeeper threatened to quit he was expelled from the house and now lived outdoors.

I’m still not entirely sure what this means, but I’m in no doubt that it means something.

Malcolm, now in her mid-eighties, may be destined to be remembered only for the opening line to The Journalist and the Murderer — ‘Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible’ — but there’s absolutely nothing indefensible about what she’s done. On the contrary, there’s everything to admire. Fearless, curious, endlessly entertaining: would that we were all so stupid and full of ourselves.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in