France has been in a state of organised uprising this week, with 300,000 motorists taking to the streets and autoroutes to protest against rising fuel taxes. One protester has died, more than 400 have been injured and even more disruption is on the way.

Watching Emmanuel Macron, you wouldn’t know it. He travelled to Berlin to commemorate Germany’s war dead, launching for the second time in a fortnight into his proposal for a single European army, and saying it was Europe’s duty to prevent the world ‘slipping into global chaos’ — apparently unable to recognise the chaotic scenes he had left behind.

It is not out of character for France’s young President, who, since being elected with lukewarm support last year, has developed an aloofness with which he would never survive in Britain’s less forgiving democracy. Whether launching coded attacks on Donald Trump or floating proposals for ever-greater European integration, he has tried to establish himself as the pre-eminent international statesman of his time, putting forward blueprints for Europe while failing to command the support of his own people for his modest economic reforms.

How odd it seems for Macron to speak of Trump as some strange aberration of western democracy when he has far lower approval ratings than the US President: just one in four French voters back his record. Were Macron to be polled on his pan-European approval rating, he would not fare much better. At a time of widespread disenchantment with the EU and its undemocratic ways, Macron has sought to make a virtue out of being tin-eared, attempting to hold Europe up as a model for the world to emulate.

The nasty underbelly of European politics is there for all to see in the rise of far-right movements across the Continent. While the US economy steams ahead, the eurozone has been unable to pull itself out of the rut it has been in since the 2008 financial crisis. A year ago, it seemed briefly as if the eurozone was on the rise again — a moment that Remain campaigners in Britain sought to use to their full advantage. Yet in the third quarter of 2018, eurozone growth fell back to 0.2 per cent. The German economy even shrank. Once again, the UK is growing only slightly faster.

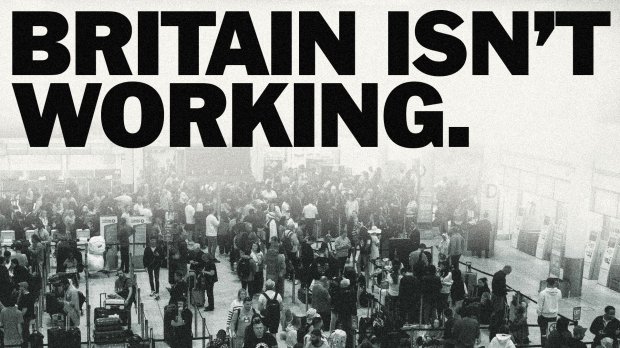

But the real difference is in job creation. The eurozone economy has an unemployment rate of 8.1 per cent, nearly twice the 4.1 per cent in Britain. In France, 9.3 per cent are out of work, in Italy 10.4 per cent, and in Spain a scandalous 15 per cent.

Britain has a productivity problem, but this is the flipside to our jobs miracle. Never in our recorded history have jobs been created at a faster rate: at first, this was at the expense of pay rises but these, too, seem to be catching up. British unemployment is now at the lowest level since 1975.

This is part of what gave the public the confidence to leave the European Union: it’s hard to think of a time when we looked to the continental economies with so little to envy. The biggest economic risk to Britain now does not come from Brexit but a new implosion in the eurozone.

Too proud to admit defeat on the single currency, eurozone leaders have condemned its weaker members to an exchange rate which is too high for their needs. Britain recently experienced the benefits of having a floating currency: a competitive pound means more exports and revived UK manufacturing — something George Osborne tried and failed to do with his umpteen factory visits. Yet the basic economic tool of a sovereign currency is denied to France, Spain and Italy — with profound consequences.

The EU remains over-regulated and over-generous with employment rights, which, while they offer some comfort to those who already have jobs, are a serious barrier to the creation of new ones. In technology, the EU’s precautionary principle is stifling innovation. The pattern is becoming eerily familiar: the US comes up with a new way of doing things — a Google, a Facebook, an Amazon — and then the EU taxes and regulates it aggressively. It is true that tech giants often behave arrogantly and do need keeping in their place, but Europe needs to ask why it is always the US which produces these fantastically successful companies. Brexiteers used to make this argument. Yet thanks to Tory incompetence, the Brexit project looks as if it will end up denying the public the advantages of a new, more liberal regulatory regime.

Brexit was supposed to give Britain a chance to escape the EU’s underperforming economic model. But Theresa May’s deal would make that almost impossible. As Martin Howe QC argues in a feature, the bad deal — if ratified — would also be inescapable. Westminster politics may be chaotic at present, but look at the wider global picture and it should be clear what is at stake. In contrast to Macron’s megalomaniac vision of EU values conquering the world, there is a politically more reserved but economically more liberal opportunity which Britain should be taking. Even now, it is not too late to seize it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in