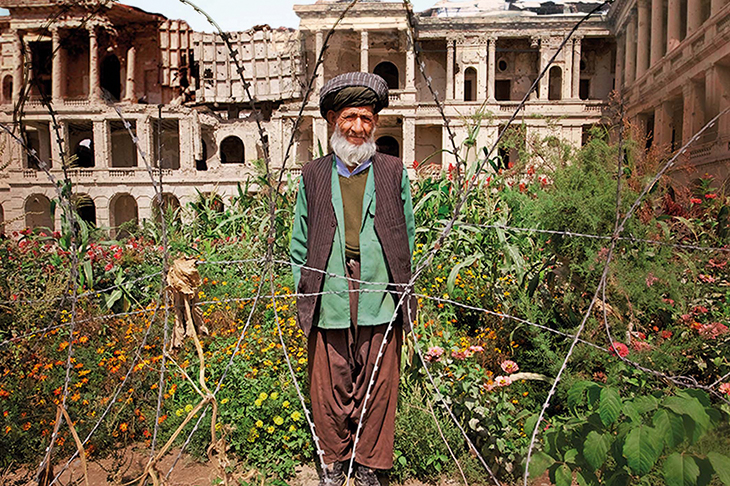

During the civil war in Afghanistan in the late 1980s, Mr and Mrs Roami, a science professor and a nurse, sent their children away from Kabul to Europe for safety. Tragically, they lost the phone number of where the children had moved to and had no way of contacting them. The couple found solace in gardening. Despite the constant explosions of rockets and shells, they were unwilling to leave their home. They named flowers after their children, and tended and spoke to them. It gave them the hope that one day the family would be reunited.

At one point, battle raged on all four sides and it was too dangerous to cross the road to fetch water from the stream. The garden was starting to die. The couple decided to build a well, and after five hours of digging, they could pull enough water from the ground. ‘Neither the rockets nor the fighting could stop us. I think that is the true story of flowers and war, don’t you?’ said Mrs Roami. One might presume gardening and nature would be a luxury in wartime. Instead, as Lalage Snow shows in this extraordinary book, it is often an act of necessary psychological resistance.

Early on, while reporting on a military operation in Nad-e-Ali, a violent district in Helmand, Snow, an award-winning photojournalist and war correspondent, noticed that when the bombing and shelling ceased, she could hear the sound of birds and bumblebees. It was ‘utterly war’, but amidst it she finds gardens of beans, cucumbers, tomatoes, vines, roses and geraniums. Later, she’s told that ‘gardening is like breathing’ for Afghans.

Intrigued, Snow visits gardens and those who cultivate them in Kabul, Gaza, Ukraine, the West Bank, Helmand and the Israel Kibbutzim over a seven-year period to find out why people cultivate and tend flowers and plants — produce would be more obvious — in war and its aftermath. The book also includes over 30 images of the gardeners she profiles.

Because nasturtiums and geraniums are seemingly unpolitical, Snow is able to interview a wide range of people who speak openly about their experience of war during and after a tour of the gardens, even if shells are thudding in the background. A string of similar scenarios could get repetitive or tiresome, but it doesn’t, because the context, scenes and characters are both remarkable and well-drawn.

Snow’s voice is warm and engaging, and she has intriguing turns of phrase: the sun ‘pulls’ the day; women ‘scatter into neighbouring homes like marbles’; a voice is ‘soft as a cobweb’. Unsurprisingly, she’s conscious of light (‘candescent’) and colour (‘glaucous blue’), and scenes often feel like a photograph magicked to life. Her language is detailed and evocative: you can smell the honeysuckle exacerbated by the morning heat. In Ukraine in 2014, some berk in a bar mocks her by suggesting she is like the hapless William Boot, the nature columnist in Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop, who gets dragooned into covering a war in East Africa, but there are no plashy fens here.

‘I feel free up here’, says Esra Ahmad in her father’s hydroponic rooftop garden in Gaza

The experience of reading War Gardens somewhat mirrors Snow’s journey —and, in the faintest way possible, the lives of her subjects. The stories told are horrific; but the passages describing the gardens are a let-up and a balm. For she sees and recounts hell on earth: a child screaming in a hospital bed, skinned by boiling water; a little girl who lay in rubble for four days next to the body of her father, executed in front of her; a head in a cabbage patch; the loss of husbands, wives and children; the loss of minds to terror. But the gardens give people strength: many say they couldn’t live without seeing green leaves and flowers.

On many occasions people see themselves as inseparable from the trees, the flowers and the land. ‘When they uprooted the olive trees, it was as though they are uprooting me,’ says one source. Nature is entwined with identity, both national and cultural, and a shared history. It is a defiant act, to maintain a garden during a war. In Gaza, Snow visits a garden of 500 cacti: ‘the only freedom I have,’ says the gardener. In another corner, a father has created a ‘little perfect world’ where his children can play and feel safe, away from the F16 rockets.

For all these victims of war, their gardens are places in which to breathe, providing moments of calm, hope and optimism in a fragile life of horror and uncertainty. For many, it helps them grieve.

Books seldom bring a lump to my throat, but this one did.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in