Asked how he achieves the distinctive realism for which his novels and screenplays are famous, Richard Price, that sharp chronicler of the American underbelly, tends to cite Damon Runyon’s biographer Jimmy Breslin, who said that Runyon ‘did what all good journalists do — he hung out’.

Set in the brutal confines of the Stanville Women’s Correctional Facility, and, through flashback, in the equally unforgiving milieu of San Francisco’s Tenderloin, Rachel Kushner’s third, extraordinarily accomplished novel, The Mars Room, glows with the kind of authentic hyper-detail only a good deal of hanging out can capture. Whether she’s describing the ‘clammy fingers of fog… and big bluffs of wet mist working their way down Judah St’, or the smell of ‘human sweat ionising on stainless steel,’ she never seems anything less than embedded.

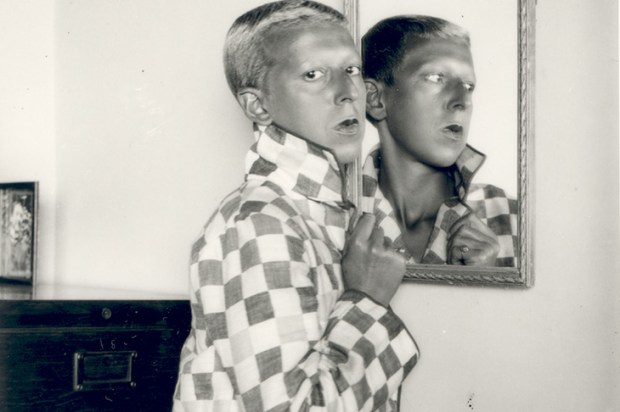

The Mars Room’s narrator, Romy, is serving two life sentences plus six years for murder. The man she killed, Kurt Kennedy, was her stalker. He was also her client. The ‘Mars Room’ is the strip club where Romy worked. Kennedy, she tells us, ‘fixated’ — following her home, calling her repeatedly, even trailing her when she fled. Unable to stand his pursuit any longer, she beat him to death.

Kushner’s great skill lies in her manipulation of focus. Through the accretion of small detail, she builds a formidably systemic world view, one in which capitalism is both merciless and inescapable. ‘I was expendable,’ Romy says of trying to get her employer to protect her. ‘Men who spent money were not.’

It’s a system that not only pits the vulnerable against each other, but which inculcates them into its machinery of victimisation. Once inside Stanville, Romy and the other women are put to work manufacturing the tools of the very system that failed them: ‘Judges’ benches. Jury box seating. Courtroom gates. Witness stands.’ With few other options, they develop ever deeper reserves of rapaciousness. When a letter arrives in the prison from a clearly vulnerable man seeking a pen pal, it’s auctioned off to the highest bidder, because ‘victim meant saviour’. Even when the women resist, they are symbolically enfolded into the established order: rules governing medication and portion size are named after the women whose complaints led to those rules being changed.

‘The rhythms of the world did not always coordinate with the rhythm of the person,’ Kushner writes. Her project is to show how those rhythms collide, and what happens to a person when they do. She succeeds beautifully, rendering visible the sequences of injustice and exploitation that underpin our society, yet never losing sight of the individual lives those processes depend on and destroy.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in