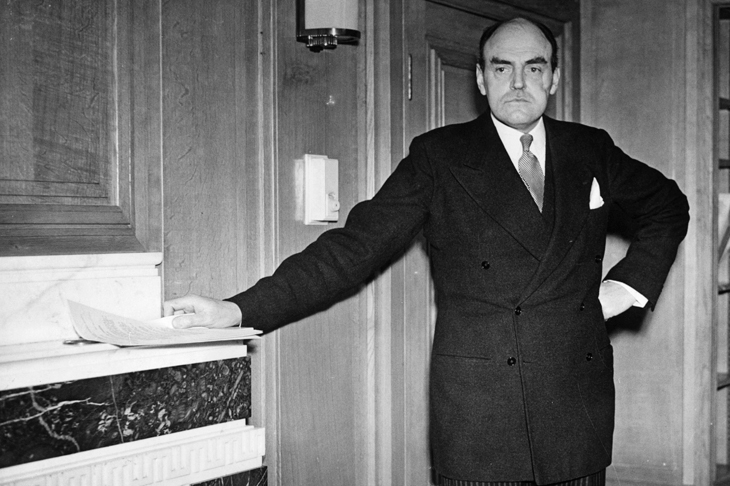

Who controls the mainstream media? Baldwin famously declared that moguls like Lord Rothermere and Lord Beaverbrook did, exercising power without responsibility, ‘the prerogative of the harlot throughout the ages’. ‘There goes the harlot vote,’ lamented one Tory grandee.

The media plays a significant role in any constitutional state, with Burke elevating those who sit in the Reporters Gallery as a Fourth Estate even more important than the other three.

Probably the best definition of the role of the media was stated by the Times in 1851. This is to obtain ‘the earliest and most correct intelligence of the events of the time and instantly, by disclosing them, make them the common property of the nation’.

The Manchester Guardian’s C.P. Scott translated this into the fundamental ethical rule for a free and responsible press: ‘Comment is free but facts are sacred’. Sadly, survey after survey today tell us that the public has great difficulty in distinguishing fact from opinion.

David Marr sees journalism as more than fact-finding. It involves a vaguely ‘soft-left’ inquiry. The New York Times’ Dean Baquet insists that a ‘real journalist’ must have ‘in his heart a desire to make society better’. No, says James O’Keefe in his recent book, American Pravda — the real journalist pursues the truth, letting citizens use that to build a better society.

So how is this fundamental conflict answered in the various media models? Lord Reith’s BBC was unique in not allowing its journalists to broadcast their opinions.

The classical model involves a number of competing media moguls, interested in both content and the bottom line, endowing their editors with considerable line authority. In a responsible newspaper, the editor is thus strong enough to require universal compliance with the rule that facts are sacred. News Limited, with an absentee mogul, is the last major example of this in Australia.

Its replacement here and especially in the US is the journalists’ collective. Instead of a mogul, we see faceless professional company directors flitting from board to board, indifferent as to whether they are governing a shoe manufacturing or media corporation. Content is left to the journalists who, surveys confirm, tend to be further to the left than the general population.

For these collectives, facts are no longer sacred and the editor reduced to a mere primus inter pares, first among equals.

The ABC goes further, becoming a collective of collectives. The board and managing director are impotent, preferring a quiet life. The collectives, each running a programme, are so powerful they are squeezing the ABC from adequately broadcasting in genres not serviced by commercial TV, such as high culture, Australian drama, rural, motoring, gardening, etc.

This model inevitably results in more bias than in the mogul model, not only in news reporting but also in the selection of news. Informal quotas emerge for virtuous items, where a narrative is adopted. Current examples are that Donald Trump’s victory was achieved only through Russian collusion and that the planet is dangerously warming because of man-made CO2 emissions. Facts countering any narrative are either unreported or heavily discounted. When acknowledged, opponents of the narrative are ridiculed as conspiracy theorists. This phenonomen can also emerge in the mogul model, but less insistently so, especially when there are a number of competitors, as in London.

All this is magnified by the way most people receive their news. Only an ageing minority seem to read newspapers – glancing at one or two selected reports on a telephone is hardly reading a newspaper. Most people receive their news through a daily television news bulletin, usually while doing other things. The small amount of news in the bulletin draws heavily on the principal news gatherers, newspapers and the ABC. Meanwhile, commercial radio distinguishes carefully between its brief news bulletins and clearly identified conservative comment, mirrored by Murdoch’s Sky TV News which offers a goodly dose of balancing left-wing comment.

Commercial television is significantly different. Political news is usually delivered by a gallery journalist who typically mixes fact with comment usually from the left or centre-left political prism.

There are many other examples of the biased narrative dominating our news. Writing on the 1999 republic referendum, the distinguished British editor Lord Deedes observed that he had rarely attended elections in any country, certainly not a democratic one, in which newspapers had displayed a ‘more shameless bias… determined that Australians should have a republic,…(and using) … every device towards that end.’

Unleashed from the ethical rule that facts are sacred, media bias will be especially directed against any conservative leader. John Howard countered this by going over the gallery and speaking directly to the people through talkback radio and breakfast TV. Donald Trump does much the same through his tweeting.

Even the mogul model can succumb to this inbuilt journalistic hostility to a conservative leader. In a report well buried in the media section of the Australian, retiring editor Chris Mitchell recently apologised for what he confessed was his greatest mistake, persuading Rupert Murdoch to support Kevin Rudd in the 2007 election, which was a national disaster.

When Tony Abbott led the democratic world and announced he would turn back the people smugglers’ boats, he was ridiculed by the commentariat in alliance with treacherous elements within his own government. This could never be done, they said, or would mean war with Indonesia. Whatever Abbott did became the subject of adverse reporting— lifesaving in a lifesaver’s garb, daring to eat an onion, winking during a radio show and doing what has been done without any adverse media comment whatsoever in over forty countries, namely awarding a well-deserved knighthood to Prince Philip at almost no cost.

It is clear that a left-wing commentariat controls the American mainstream media. When Rupert Murdoch leaves us, Australia will probably follow with the result that in our news, facts will no longer be sacred but will be even more consistent with the latest narratives of the Left.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in