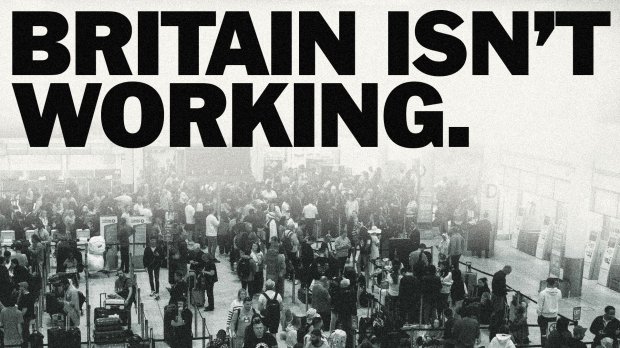

If Brexit was going to be as easy as some of its advocates had believed, we would not have had weeks such as this one. It’s hard to interpret the recent agreement over the transition period as anything other than a capitulation to EU demands. Theresa May has quietly scrubbed out her ‘red line’ on the rights of EU citizens and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice. Nationals of other EU countries will be free to move to Britain, seek work here and have their rights protected by the court until 31 December 2020. Moreover, she has agreed to UK waters being open to EU trawlers until that date. Indeed, to the chagrin of our own fishing industry, fishing quotas will be set for our waters in 2020 — without the UK even having a say as to what they should be.

Perhaps most worryingly, the idea that Northern Ireland could remain permanently in the customs union — which Theresa May once said ‘no British prime minister could ever concede’ — remains on the table. This brings about the prospect of an internal border within the UK in the Irish Sea — a situation which ministers know will prove unacceptable to a very large proportion of Northern Irish residents, not least among them the DUP, on whose votes the government relies for support. If the government does fall on a confidence vote before the projected date of the next election, in 2022, its demise may well be traceable to this week.

The government has found itself in this position thanks to a woeful lack of preparation for the Brexit negotiations. In her Lancaster House speech of January last year, Mrs May appeared to have a viable plan for Brexit: to withdraw from the single market and the customs union, to negotiate in their place a free trade agreement, and to opt back into EU programmes where the government saw fit. But since Article 50 was triggered it has become increasingly and painfully clear that the government has no negotiating strategy to get to this point. Instead, ministers have allowed themselves to be buffeted around by an EU negotiating team that has seemed to have more purpose and direction than its counterpart.

Michel Barnier has been criticised for his obstinacy and his lack of imagination in solving issues such as the Irish border. It is true that his constant stonewalling of suggestions put forward by Britain shows the EU in bad light and is a reminder of the freedoms we might enjoy outside the bloc. His tone has been needlessly caustic, and he has seemed to take the Brexit talks as an audition for succeeding Jean-Claude Juncker as president of the European Commission. But his stubbornness is working: putting Britain on the back foot, forever struggling to defend itself. The government’s failure to come up with proposals has left a vacuum in which the EU is suggesting them for us.

The EU can get away with this because the government is in no position to walk away from the negotiating table, or even to threaten to do so. EU negotiators can see this, and have been able to behave as if a trade deal were a one-way concession to Britain, rather than an agreement of mutual interest. There are commercial interests across the EU who have grown impatient at times with Barnier, but the UK government has failed to make common cause with them.

Also, the member states’ power over the European Commission is waning. In Britain, the EU is often thought about as a single entity — and one that in the end will do whatever Germany says. But Angela Merkel is struggling to exert control over her own government, let alone the continent. Juncker and Barnier see an EU that does not take its orders from member states, but draws (or claims to draw) its own democratic legitimacy from the European Parliament. The EU member states have an interest in a good deal with Britain. But the European Commission — the apparatus in Brussels — has an interest in Britain being seen to be worse off after leaving the EU. The Commission would also receive 80 per cent of the tariff revenue from UK exports to the EU, making ‘no deal’ more appealing to Brussels than to member states.

It will come as no surprise if the £37 billion leaving bill is jacked up. Nor can we rule out having to stay in the customs union — thus being unable to cut our own trade deals with the outside world. But even this relationship would be better than remaining in the EU: the main aim of Brexit was to make government more answerable to the people, to restore democratic control over laws, taxes and borders. That’s why, after all of these setbacks, Brexit remains as popular as ever. If there is one thing to be said about this week’s transitional deal, it is that the Prime Minister has won herself a little breathing room. But she will have to use it very wisely if she is to stop Britain from falling into a Brexit which will not deliver the benefits that it could or should.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in