I grew up knowing 1947 as the year of my father’s birth, in a black-and-white faraway time. I was told about rationing and petrol coupons, as yet another chapter in the long book of ‘how good you have it now’ — along with chilblains, measles, castor oil and walking ten miles to school neck deep in snow, uphill both ways.

The Swedish author Elizabeth Åsbrink presents the year as the fulcrum of modern history, when ‘everything seemed possible, as it had already happened’. Month by month, she shows us the year through the eyes of a disparate cast of characters. Some of them are well known (George Orwell, Simone de Beauvoir, Chuck Yeager, Primo Levi), some are passers-by who happened to be in history’s path.

Åsbrink has dug into archives to find individuals whose experiences are synecdochic, such as the Palestinian girl whose house is attacked during the Nakba, or a young Romanian Jewish refugee trying to leave Europe.

The leitmotif of the book is the establishment of Israel, primarily told not through the actions of many kibbutzim or Zionists, but from the perspective of the handwringing UN committee and flailing British administration. We see the concentration camp survivors adrift in a Europe unsure of what to do with them, and desperate to find a new home. Some are desperate enough to climb aboard an overloaded, repurposed American ferry, with barbed wire on the railings, to try to reach Palestine — but we only hear about, not from, them.

Another of her themes is the city of Malmö as a staging post for Nazis fleeing to South America. Per Engdahl engineered a network of fascists to help Nazis escape, and also to build links with fascist groups around the world. (Some of Åsbrink’s earlier journalism exposed the links between prominent Swedes and fascism.) She returns to events in Malmö through the year, as Engdahl’s work grows, particularly through the fascist newspaper Der Weg.

Her snapshots are atmospheric and impressionistic. This is in its way a reminder that even at the time, nobody saw the whole, or understood all. Each person was focused only on their own situation. Her selection of participants is idiosyncratic — another author could take the same approach and focus on a completely different cast.

The partition of India we see from the perspective of Mountbatten, not Punjabi civilians. We learn of their suffering at one remove. But many other parts of the world are ignored altogether. We see nothing of Japan adopting its post-war constitution —with its famous non-aggression clause (surely a significant event in shaping the modern world). The reader will search in vain for any reference to the Chinese civil war — or the anticolonial struggles in Indochina and Indonesia. Of course a book like this cannot cover everything, but it is very Europe-focused. The ‘now’ of the title is the now of Europe.

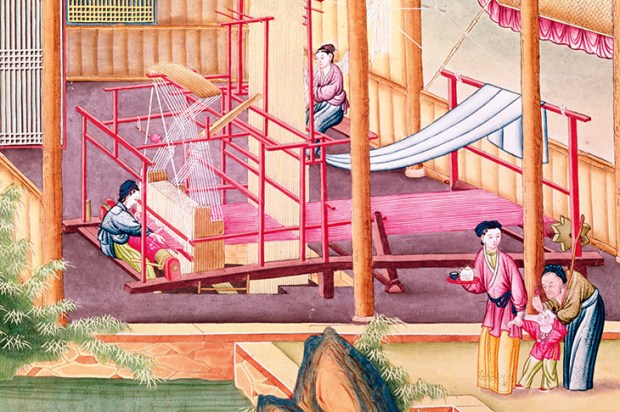

We see Christian Dior launch his New Look, which offended many as an emblem of conspicuous consumption when fabric was still in short supply (one small error: a Diorama skirt was 16 metres in circumference, not diameter). It is a stark reminder that this luxurious fancy, for those wanting to put that whole nasty war behind them, was taking place even as Nazis were still being tried, and Raphael Lemkin was still struggling to have genocide accepted by the UN as a crime.

This is for the author a personal story, the story of her father, a Hungarian Jewish boy. Aged ten in 1947, he had survived the Nazis, only to end up trapped behind the Iron Curtain. We see the Cold War ramping up, stage by stage, not always clearly — just in people’s peripheral vision, a cancelled election here, a border check there.

Åsbrink’s image of a scarred Europe says nothing of the bustling maternity wards, and the baby boom that would create our new future. Surely this is part of what makes 1947 the start of now, with the birth of so many who would shape the coming decades. The lack of an index is a weakness, as the experiences of individuals are returned to throughout the book. The idea of 1947 as pivotal in shaping the modern world is also tenuous — a historian could as easily make a case for 1919, 1933, 1941, 1968, or even 1989. But Åsbrink’s elegant prose (translated by Fiona Graham) offers a lyrical history of a year that seems both recent and ancient.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in