Patricia Daunt’s collection of essays is a fascinating exploration of some of Turkey’s most beautiful and evocative places, from the crumbling grandeur of Count Ignatiev’s Russian embassy summer villa on the upper shores of the Bosphorus to the remote and fog-bound manor houses of the Black Sea. But the Palace Lady’s Summerhouse is much more than a beautifully illustrated book: it’s about the people who lived — and live — in these buildings, and a portrait of the vanishing worlds they represent.

We meet the gentlemanly descendants of a dynasty of grand viziers who quizzically watch the maritime traffic of the modern world passing by their ancestral waterside palace. There are cheerful black peasants whose great-grandparents came to Turkey as slaves and settled on the shores of Lake Köycegiz, a rarely visited gem in western Anatolia; and gentlemen tea-farmers who spend winter evenings sitting in the vast inglenooks of ancient farmhouses. It’s a whimsical and finely drawn account, a love letter to a country and to a world that has been almost completely swallowed up by tourism, new money and development.

Daunt, the wife of a former British ambassador to Turkey, has been able to visit and document houses, palaces and grand Bosphorus villas — known as yalis — rarely seen outside a tiny circle of diplomats and Istanbul grandees. The section on ‘palaces of diplomacy’ takes us inside some of the grandest mansions in Istanbul. Almost all of them were purpose-built by the great powers to show off their wealth and power to the Ottoman court. Hence Pera House, the current British consulate-general, is a vast pile designed by Charles Barry who also built the Palace of Westminster. The Netherlands have a perfect early 18th-century Dutch manor house; the Italians a Venetian palazzo; the French a baroque hotel particulier, furnished in Louis XVI style.

But it is Daunt’s journeys into the back corners of Turkey’s own heritage that are the most fascinating. In a country that (until recently at least) was swamped with tourists, Daunt manages to seek out places almost untouched by the currents of the modern world. The exquisite mosque complex at Divrii in central Anatolia, for instance; or the traditional wooden farmhouses that cling to the hillsides of the tea-growing valleys above Trabzon; the basket-weave fishermen’s huts of Mugla; and the ruins of Aphrodisias — every bit as impressive as Ephesus but much less visited. She visits artists’ villas, peasant farmsteads and cotton plantation houses, interviewing the residents and exploring the spirit of these places through their still-living history.

What brings these various essays together is a sense of bittersweet nostalgia for a lost Ottoman world that is common to both palace and hovel. One of the grandest yalis of the Bosphorus cowers in the shadow of a soaring road bridge; over the hills from the dancing waterside light of Lake Köycegiz are rows of high-rise, all-inclusive beachside hotels that have disfigured the coast of Marmaris. Opposite the yali terrace, where the aristocratic owners once hosted elegant swimming parties in the 1950s and entertained the boisterous King Faisal II of Iraq, an open-air nightclub thuds music across the water into the small hours.

Daunt’s writing has itself been something of a well-kept secret over the past quarter century, as these essays have all appeared in print only in Cornucopia, the greatest magazine you’ve never heard of. Begun nearly 30 years ago by John Scott, a resident of Istanbul, Cornucopia has chronicled the art and history of Turkey with intelligence and taste — but quaintly still resists the internet age by only putting small excerpts of its content online.

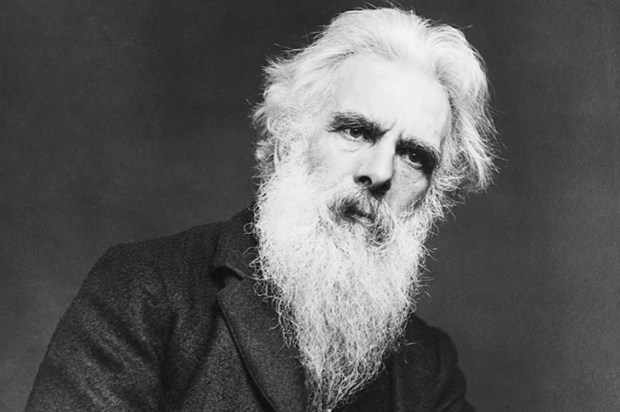

Until now, Cornucopia has been a kind of in-house secret for the sort of literary connoisseurs who frequent Chelsea’s John Sandoe bookshop. With the publication of this book, Daunt’s chronicles — illustrated with haunting and lovely photos by Fritz von der Schulenburg, among others —are finally available to a wider audience. An unexpected treasure.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in