The assignment of books for review has always been haphazard. Fellow fiction writers can be tempted either to undermine the competition, or to flatter colleagues who might later judge prizes or provide boosting blurbs. There are no clear qualifications for book reviewing — perhaps publication, but most of all, because reviewers are paid for their text but not for the many hours it takes to read the bleeding books, a willingness to work for atrocious wages.

Mitigating the gravity of this matter? Aside from the authors whose work is on the block, almost no one reads book reviews, and I say that as someone who writes a fair number. It’s a publishing truism that ‘reviews don’t sell books’ — although negative ones can un-sell books. With lose-lose odds like that, why books are ever shipped out for review is anyone’s guess.

The lofty New York Times seeks to prevent literary back-scratching by making reviewers swear on pain of excommunication that they are not friends with the author (the test being whether you’ve dined together). With young adult titles, Kirkus, an American trade journal that can influence library and bookshop orders, has raised the moral purity bar still further.

YA fiction reviewers must identify all characters by race, religion and sexual orientation. (Kirkus reviews are only 200 words. After all that ‘African-American, lapsed Buddhist, male-to-female transgender with a foot fetish’, I’m amazed there’s any wordage left.) Should authors have been stupid enough to include a ‘diverse’ cast, their books will be assigned to ‘own voices’ reviewers — that is, other African-American, lapsed Buddhist, male-to-female transgenders with foot fetishes — the better to ‘call out’ writers guilty of any crimes of the imagination on the burgeoning list of progressive no-nos.

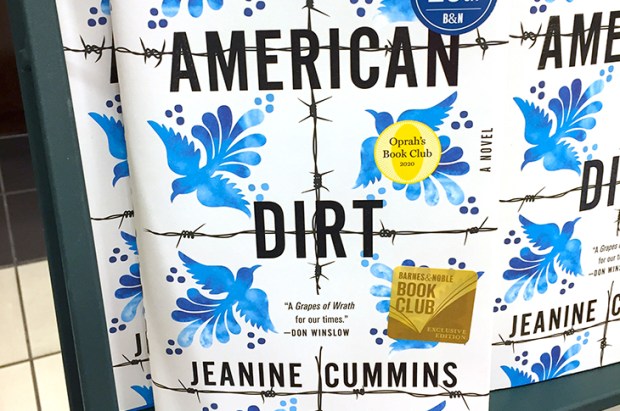

Laura Moriarty’s American Heart is a dystopian tale about a white 15-year-old girl who meets an Iranian academic on the run and comes to realise that America’s corralling all its Muslims into internment camps is not very nice. Thus the Kirkus editor-in-chief assigned the book to a female ‘observant Muslim of colour’. The Muslim reviewer gave the novel an enthusiastic notice, which merited the coveted Kirkus star.

Something peculiar seems to have happened amid YA readers in particular. Even for our fevered times, the social justice outrage in this ‘community’ rapidly reaches a pitch that could shatter crystal. Crusaders on social media (most of whom hadn’t read the book) denounced Moriarty’s novel as promoting a ‘white-saviour narrative’. Kirkus took the review down. Asked if she would please like to reconsider her appraisal in light of the frenzy online, the reviewer rewrote her review to be more critical. Kirkus posted the new version. It retracted the star.

I’ll reach for an adjective grown painfully fashionable; maybe in an era of hyperbolic huffing and puffing, commentators welcome its ambience of understatement: troubling. This story is troubling.

The ‘own voices’ policy conveys to reviewers that their primary job is not to assess a book’s storytelling, but to rate its adherence to a left-wing catechism (the fairness of whose tenets is presumably self-evident), to identify authorial heretics, and to stick the apostates’ heads on spikes along the digital public highway. Reviewing for Kirkus is now a cross between penning literary criticism and joining a shooting party, a sufficiently athletic undertaking that it really should pay better.

I’ve despaired previously of YA publishers’ use of ‘sensitivity readers’ to screen manuscripts for politically objectionable content, of which this practice is an extension. Since reviewers sent searching for sin redeem their existence by becoming offended, what makes the American Heart story extraordinary is the fact that the original reviewer, a practising Muslim, thought a novel by a white writer, with a Muslim as a main character, was wonderful.

There’s no reason why sensitivity on steroids will remain restricted to YA fiction. Across the genres, the sanely self-protective response to this scrounging for sacrilege is surrender. For writers to create a ‘diverse’ cast of characters is not worth the risk. The YA author Justine Larbalestier has already bannered proudly online that she will no longer use ‘persons of colour’ as ‘protags’ — a usage alone so horrifying that it should really disqualify the woman from writing about anybody.

Am I the only one to find the #metoo-ing over Harvey Weinstein a little creepy? Bandwagons always make me want to jump off. And talk about kicking an asshole when he’s down. I resent being made to feel sorry for the man.

Now that the confessional groundswell over sexual harassment has moved far beyond this one Hollywood toad, we seem to be losing the distinction between actual sexual assault and mere poor taste. The theatre director Max Stafford-Clark’s remark to a staff member that he would be ‘up her like a rat up a drainpipe’ in his friskier days sounds like the arm chancing of an earlier generation, and at 76 he was unlikely to have made a young woman feel threatened. He was in a wheelchair, for pity’s sake. So was George H.W. Bush, when rumoured to have patted the odd behind. An increasingly senile old goat with reduced inhibitions couldn’t have been that scary. Bush Sr doesn’t have much power to abuse, either. There’s a big difference between the ‘sex pest’ whom you can bat away, and the kind you can’t.

I worry, too, that in the extremity of our reaction to the Weinstein case, we women are frightening men to such a degree that they will never venture an off-colour aside in mixed company (since none of us prudes have a sense of humour). Much less will they ever dare to lean over a dinner table that tad too far when you’re both married and ought to know better.

I treasure a little lightheartedly suggestive banter that you both realise will never materialise into anything dangerous. I savour the playful electric frisson between sexes — the passing dalliance, the fleeting reciprocal attraction that will evanesce, but which still puts a spring in your step walking home. Mutual flirtation could become a bygone art, and a bygone pleasure.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in