There are three reasons why Britain’s political and media world finds itself in the present ludicrous uproar over sexual misbehaviour at Westminster, and only one of them has anything to do with sexual misbehaviour. But let us start with that.

And, first, a caveat. Can there be an organisation anywhere in discovered space which, subjected to the intense media scrutiny that the House of Commons now attracts, would not generate a comparable stock of report and rumour? Imagine a workplace — indeed imagine a workplace like our own august Spectator offices – peopled by a lively mixture of creatives, eccentrics, wannabes, rascals, saints, absolute bricks, total pricks and drones. Now add to this mix the supposition that anything private and sex-related (on or off duty) involving any of these people virtually since puberty — anything on a scale ranging from the saucy through the inappropriate to the shameful and the downright criminal — is considered hot news and a matter of urgent national importance.

Remind you of anywhere? Your own street? The BBC? An Inn of Court? British Airways? The Royal Opera? A teaching college? The Met? All would be in the firing line. Yet people in these institutions are now working themselves up into a state of great agitation about the behaviour of those employed at Westminster. The hypocrisy may be unconscious but it is striking.

While accepting this caveat (that it’s the raging media demand rather than the available human supply that has created the impression of a modern Sodom and Gomorrah on the banks of the Thames), I do nevertheless think that political life attracts an untypically large number of male chancers. If you weren’t a chancer, why would you seek election in the first place? Combine the buccaneering disposition of a risk-taker with what Noël Coward called ‘this sly biological urge’, and hands will undoubtedly brush knees and much, much worse. Deprive Westminster of its buccaneers and you deprive it of some of its best as well as its worst.

My own view (should you care) is that the pendulum has swung too far but that it’s in the nature of pendulums to swing, and this one needed to. Some horrible stuff has been uncovered, and unless you wish it had not been, you must accept that without the current sense of alarm, many individuals would never have broken their silence. We hope in vain if we hope for some precise Aristotelian mean between going too far and not going far enough.

There will therefore be cruel casualties of this forest fire before it burns itself out, and great unfairness, and I can’t say I’m comfortable about it; but so there were during the eerily similar MPs’ expenses scandal. Media alarm is a blunt instrument. But some men needed a big fright, and all over Britain we’ve been revisiting our own behaviour. Two cheers for that.

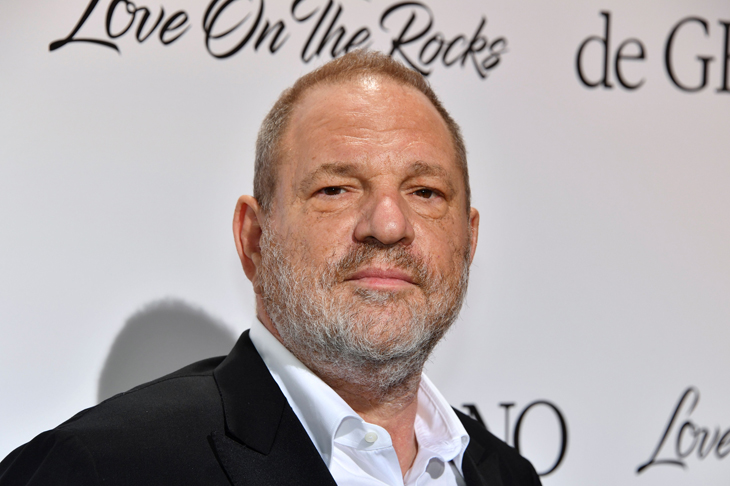

To this 2017 firestorm, Harvey Weinstein was the spark. But why was the brushwood so astonishingly dry? This brings me to the second reason why politics and sex have proved such an intoxicating cocktail this autumn. People can understand sex.

Never underestimate the difficulty of arousing interest in a matter of national importance, if the matter is complicated. Democracy bestows upon the populace a right to an opinion on large political questions, but it does not always bestow the gift of understanding them. In Parkinson’s Law, C. Northcote Parkinson maintained that in any board meeting the amount of time devoted to an item on the agenda will be in inverse proportion to the difficulty of the issue. Whether to build a vast nuclear reactor, he suggested, might detain the board for a few minutes but they’d spend half an hour on the design and cost of the bicycle sheds. They knew what a bicycle shed was.

Journalists and voters know what sex is. We all have first-hand knowledge of questions of propriety in the making of sexual advances. We understand the dilemmas and ambiguities, the mistakes you can make and the way people feel. The debate about sexual lunges by politicians is therefore capable of infinite extension, inspiring lively interest and a wealth of compelling personal stories. We relate to it in a way we don’t to the Gatt.

The sheer accessibility of the topic, I believe, has made it the perfect candidate for something psychoanalysts call ‘displacement activity’. Displacement is the re-channelling of anxiety or frustration into comforting behaviour, unrelated to the real source of the tension. We energetically re-arrange our desktops, tidy the kitchen, chew gum or make yet another cup of tea: we throw ourselves into the familiar to distract ourselves from a problem that’s too big for us.

Which brings me to my third reason for this alarum. From what might we be running if Britain in 2017 is throwing itself furiously into a political question it can at least understand or even answer? Might there be an infinitely bigger problem we are trying to avoid: a political dilemma from which we turn in anxious confusion? The question need only be put for the answer to suggest itself.

Historians years hence will examine the politics of this hour, read the newspaper headlines, commentary and leading articles, listen again to the breathless broadcast bulletins as yet another hand was revealed to have brushed against yet another bottom, and wonder what the hell we thought we were doing. ‘Britain was hurtling towards a great unknown,’ they’ll gasp, ‘and Britain knew it. Some feared it spelled ruin; others, peering anxiously through the fog, saw a vision of paradise. Their prime minister, meanwhile, teetered on collapse and their government was riven. The crisis called for all their focus, all their energy and attention.

‘But what was everybody talking about? The past sexual misdeeds of their politicians.’ Sex-pestering MPs are set fair to become the Great Evasion of the era.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in