Imagine Ryan Moore getting caught on the line by a rival’s late spurt at the end of a Newmarket race and being so upset that he goes to bed without supper, crying like a baby. Then imagine him offering to recompense the owner personally for his lost bets. That is how the popular George Fordham, champion jockey 14 times between 1855 and 1871, behaved after losing that way in 1962. Famed for his scrupulous honesty in the days when racing was riddled with corruption, Fordham has attracted less attention than his younger rival Fred Archer, known as ‘the Tin Man’ for his relentless pursuit of money. But when the two of them met in the two-horse matches that were common at the time, it was Fordham ‘the Demon’ who regularly came out on top. Archer may have won five Derbies to Fordham’s single victory in 22 attempts, but the latter’s record of seven 1,000 Guineas victories among his 16 Classics still stands.

Rivals say that the hardest thing when riding against Ryan Moore is trying to gauge from his demeanour any clue as to how well or badly his mount is going. Fordham was also known as ‘the Kidder’, often fooling his opponents into employing the wrong tactics. He preferred a gossamer touch on the reins to his rivals’ frantic whip-wielding and spur gouging and even today’s jockeys would benefit from studying his sympathetic views on how to ride two-year-olds. In The Demon (AuthorHouse), Michael Tanner reminds us how in the Victorian era, with horses an everyday sight, racing was the most widely supported sport both among the public and the massive-stakes gamblers of high society. The top jockeys were richly rewarded — a ‘present’ of £500 for a big race victory was common — but lives were shorter. Fordham was not the only jockey of his time to die of pulmonary tuberculosis. Riders ‘wasting’ to keep down their weight lowered their resistance to consumption, the silent killer of Victorian Britain.

As ever with Tanner’s well-crafted histories, The Demon is full of characters such as ‘Carrie Red’, the Duchess of Montrose, who founded a church in her husband’s memory and then berated the vicar for praying for fine weather when she needed soft going for her horse in the St Leger.

One of those characters, the former prizefighter John Gully, appears again in The Stakes were High by Keith Baker (Pitch Publishing). Gully was one of the founding fathers of bookmaking, profiting handsomely from providing betting markets for the common man. Until then, gambling had been mostly personal wagers among a ring of 100 or so dissolute aristocrats. Gully started by placing commissions for the society connections he had made as a fighter, but soon the butcher’s son whose fighting career began in the Fleet debtors’ prison built a shady intelligence network of informants. Gully did well enough from his bookmaking to buy a colliery, quality racehorses and a grand estate, and ascended into the upper classes as an MP. His bitter rival was William Crockford, founder of the gambling club, and after a series of mutual bad turns the infamous 1844 Derby became a grudge match between them. Neither won: both their horses were nobbled, quite possibly by each other, and the ‘winner’ Running Rein, who mysteriously disappeared after the race, was disqualified. He had been a four-year-old ‘ringer’ in the contest for three-year-olds.

You cannot fault the immense industry of Peter Corbett’s Bahram & the Aga Khan III (Rinaldo Publishing) but reading it reminded me of my old headmaster’s report. ‘Oakley’, it said, ‘must learn to give the examiner the cream from the top: not the whole bottle.’ Triple Crown winner Bahram was the Aga’s only great horse but we are on page 342 before we get to him. Pages 485 to 623 are indices, statistics and appendix. It is simply all too much, as is the profusion of exclamation marks and the careless misspelling of Gandhi on at least a dozen occasions (given the importance of India to the Aga Khan). What rescues the enterprise is the anecdotage. Challenged about drinking alcohol, the old man declared, ‘I am so holy that I turn wine into water.’ The Aga Khan couldn’t tell his two clearly distinguishable Derby runners, the winner Blenheim and Rustom Pasha, apart, and his political forecasting was no better. Despite professing loyalty to Britain, he sold his best horses to America because he expected Hitler to win the war.

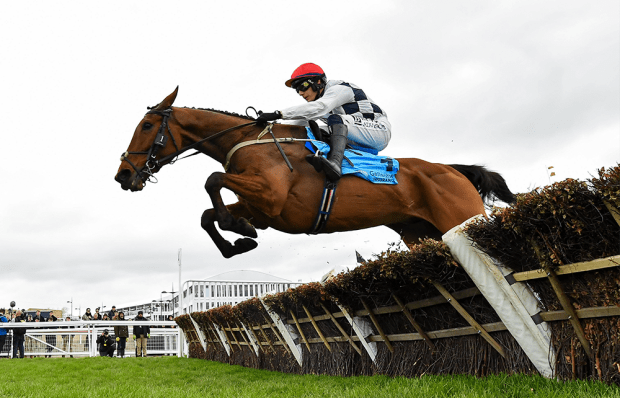

Petite Etoile, the last good prospect the Aga Khan bred, figures along with 49 other great fillies and mares in Queens of The Turf (Racing Post), a pen-portrait compilation edited by Andrew Pennington. All the favourites are there: Sceptre and Pretty Polly, Dawn Run and Quevega. Lester Piggott’s foreword says that Petite Etoile was the best filly he rode and he recalls Park Top’s farewell when she was beaten at short odds in Paris. The crowd booed, and then went berserk when her owner, the Duke of Devonshire gave them the old two-fingered salute. Clearly an early Brexiteer.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in