Few publishing phenomena in recent years have been as gratifying as Chris Kraus’s cult 1997 masterpiece I Love Dick becoming a signifier of Twitter and Instagram chic. The ‘lonely girl phenomenology’ it exemplified has now attained cultural status, with first person, inventive writing by women often enjoying centre stage.

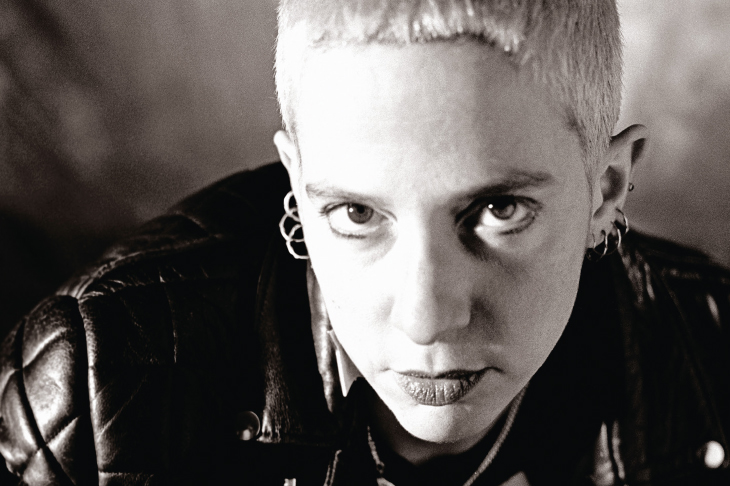

It’s interesting, then, that just as the wider culture has caught up with her, Kraus has pivoted away, delivering ‘what may or may not be a biography of Kathy Acker’ — the underground punk novelist who is still, even 20 years after her death, awaiting the recognition she deserves.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in