Last month Hong Kong celebrated the twentieth anniversary of its 1997 handover. In those far-off days many Hong Kongers felt misgivings and even resentment about being summarily ‘handed over’ by the British to the repressive Communist hegemon they had been fleeing from since 1949. In his diary Prince Charles picked up on this mood, referring to the Chinese leaders as ‘appalling old waxworks’. Still, there was excitement too. Hong Kongers were Chinese, after all. The agile local economy was nearly a fifth the size of the whole mainland’s. The colonial yoke was being shaken off. Surely this still-torpid Leviathan was unlikely to jeopardise the new jewel in its own crown. The so-called ‘one country, two systems’ arrangement, set out in a Joint Declaration, guaranteed existing freedoms for fifty years, with some prospect of genuine local elections by the end of that time.

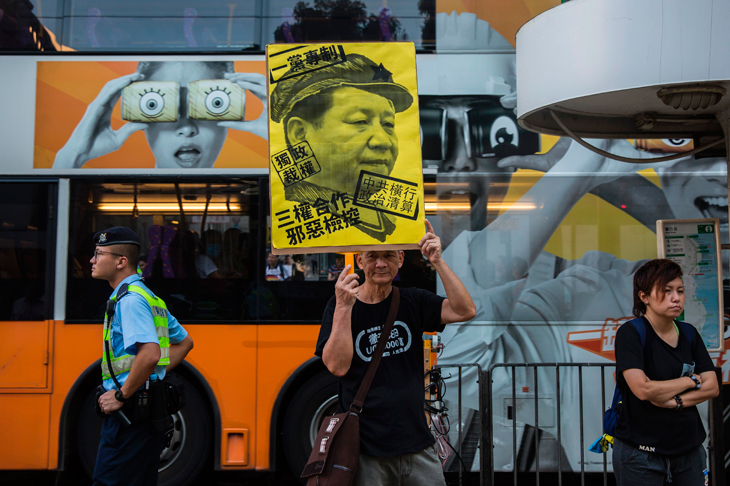

Last month, however, the local mood was of widespread disillusion, deepest among the young. Those highly orchestrated ‘celebrations’ were unilateral. The Leviathan economy has boomed since 1997; Hong Kong’s GDP is only three per cent of the mainland’s now. During his two-day visit Xi Jinping did what presidents do: he presided. But it would be unwise as well as inaccurate to call him an appalling old waxwork. The symbolic centrepiece of his visit was an inspection of the city’s large PLA garrison, which greeted its Leader with exceptional enthusiasm. Hong Kong’s new Chief Executive, Carrie Lam, Beijing-anointed heir to the outstandingly unpopular C.Y. Leung, her ‘election’ by a mainland-dominated committee just as bogus as her three predecessors’, her function as a Beijing puppet even more evident, was sworn in. Ten thousand police made sure no demonstrators got anywhere near the action. The city had been more or less silenced.

The New York Times ran two contrasting stories about this depressing anniversary. On its front page Chris Patten, Hong Kong’s last British Governor and a key player at the time of the handover, asked two questions: ‘has Beijing betrayed Hong Kong?’; and ‘can China be trusted?’ Lord Patten refrained from answering his own questions, but his clear implication was that it has, and it can’t. He sounded quite affronted. Meanwhile, economist and commentator Joseph Lian Yi-Zheng, sacked from the Hong Kong Economic Journal last year for being too critical of Beijing and its Hong Kong surrogates, explained ‘China’s Ways of Empire’. For over 2,000 years the Chinese central authorities, on broadly Confucian principles, have used the same strategy to handle new or recalcitrant provinces. A local overlord is allowed to retain his powers in return for paying tribute and kowtowing to the emperor. Then, over time, as the centre grows stronger, it replaces the local chief with its own district officers and laws. This is exactly what’s going on in Hong Kong now, argued Lian, as Beijing’s Central Liaison Office assumes more and more control over local government policy. Beijing even announced at the time of Xi’s visit that the Joint Declaration ‘no longer has any real meaning’.

Remember this is a city which has recently seen booksellers and a billionaire abducted across the border; an anti-Beijing journalist attacked with machetes; an attempt to introduce a ‘moral and national education’ school curriculum containing no mention of the Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward; ramped-up efforts to influence the internal affairs of universities; constitutional questions shunted upwards for interpretation by the National People’s Congress, instead of local judges; and the student and academic leaders of the peaceful ‘Occupy’ or ‘Yellow Umbrella’ pro-democracy movement in 2014 now faced with absurd jail terms advocated by government lawyers.

Remember, too, that Carrie Lam was the senior responsible civil servant during Occupy. She showed herself to be as uncommunicative as C.Y. Leung, her then boss, a man notable mainly for long policy addresses on such pressing matters as non-slip public lavatory floors and longer green traffic light intervals. Sheer frustration with these authoritarian silences may be why in a recent university poll only three per cent of young people aged 18-29 identified as Chinese: 94 per cent as ‘Hong Kongers’. That is extraordinary. Large numbers of the young also now say they support ‘independence’, however impossible and foolhardy this aspiration clearly is. Yes, they are upset that the boundless pressure on property prices from the mainland means they will never own their own homes in their own city: and that the influx of mainland job-seekers is making it harder for them to find work. But what is going on here is much deeper, an almost tectonic clash of values, of languages, even of civilisations. Hong Kong is right on the fault line.

The city’s twenty-somethings, the key generation during the run-up to 2047, feel that all their appeals to democracy, liberty, rights and equality might as well be the bleating of lambs for all the recognition the two governments are giving them. They sense that the rival, pseudo-Confucian language of patriotism, security, duty and sovereignty is merely a gloss on the eternal Chinese verities of face and kowtow. For the young people of Hong Kong, as in the liberal West, ‘trust’ means open covenants openly arrived at, Joint Declarations that mean what they say, Enlightenment affirmations that the truth is self-evident and all men are created equal. But in Chinese, trust or xin-ren means literally ‘heart-humanity’, a reciprocal esteem forged over a lifetime, or many. The default attitude is distrust of anyone who isn’t in your network: generally of anyone who isn’t Chinese (attention ‘Belt and Road’ enthusiasts). Which is why young Hong Kongers saying they don’t feel Chinese is so shocking.

Yes, Western liberalism can seem naive, abstract, presumptuous. Unhappily for its adherents, it also seems anaemic when disconnected from its deeper Christian and classical sources (as it usually is today). But still, its more red-blooded Chinese rival does tend towards suspicion and fatalism. And at least the Western model of trust can open the world up, make deals with strangers, animate the creative innovator. The Chinese version tends to close down horizons, to limit itself to the known, the trusted few, the ancient methods. Lam and her successors must, really must, as their first responsibility, find a way to square this circle: to speak to the Chinese hearts and Western minds of those who will inherit this city. Silence is the real enemy here. If they fail the Lams and their overlords may lose face, but the lambs could lose their lives.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in