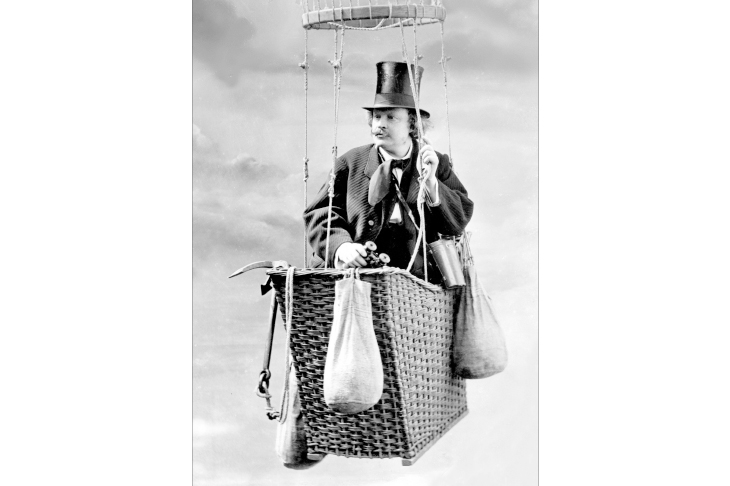

It’s quite a scene to imagine. A maniacal self-publicist with absurd facial hair takes off in what’s thought to be the biggest hot-air balloon the world has ever seen. Adoring crowds gather to watch the launch. He rises rapidly and sails off towards the clouds — but in due course the whole thing goes arse-up and he comes clattering to earth, narrowly escaping with his and his crew’s life. Never mind: the catastrophe is reported around the world and has made him even more famous than he was before. It was a ‘semi-unsuccess’. And within weeks he’s back planning another ascent in another giant balloon.

As if to bear out the wise view of Ecclesiastes that there is nothing new under the sun, the year in this case is not 1987 but 1863; and the balloonist is not Richard Branson but Félix Tournachon, known around the world by his nickname Nadar. (He was dubbed ‘Tournadard’ as a young man by his friend Auguste Lefranc; which in turn became ‘Nadard’ before ‘the final d dropped off for good in about 1849’.)

Nadar has been having a bit of a moment lately. Featuring heavily in Richard Holmes’s 2013 ballooning book Falling Upwards, and Julian Barnes’s Levels of Life, the same year, this wayward and beguiling 19th-century gadabout is now the subject of a fine short book by John Updike’s biographer Adam Begley.

Nadar was many things in his energetic career. He was a decent caricaturist, a prolific if patchy writer, a first-rate photographer (Roland Barthes thought him the greatest of all time), a reckless aeronaut — and a publicist of preternatural genius. Imagine a cross between Richard Branson, Lord Snowdon, Andy Warhol and Donald Trump (his photographic atelier in Paris was surmounted by a 50ft illuminated sign reading ‘Nadar’, and when Victor Hugo wrote to him it was sufficient to address the envelope ‘Nadar, Paris’); though more charming than all four put together.

Félix was born in 1820 to a family of the just-about-managing sort — his father Victor was a printer who managed to keep his head on his shoulders through the turbulent years after the Revolution; his mother was of (slender) independent means. Flaky but intermittently brilliant at school, he never took his baccalaureate — his father’s death intervened — and as a young man left provincial Lyon and his medical studies to dive into the Parisian equivalent of Grub Street.

His temperament suited him well to it: a flâneur and a dandy, lanky and energetic, lacking in focus and prey to wild enthusiasms and ambitions. In his forties he wrote of himself (‘simultaneously self-lacerating and self-congratulatory’, as Begley notes) that he was

a dabbler […] without moderation or restraint, exaggerated in all things, impatient in discussion, violent in speech, obstinate rather than persevering, enthusiastic about nothing, skeptical of everything, a mistrustful embracer of all quarrels, a picker-up of people who are down, always on the move and therefore stepping on everybody’s toes, which those who have corns will not forgive.

He had, though, a great gift for friendship. As a young man he pelted his neighbour Charles Bataille’s hat ‘with a volley of oyster shells’ from his fifth-floor terrace. Bataille sent up a shirty message on his calling-card (‘Sir, you drop your household garbage on my head, — I send you my address’). Félix sent a friendly invitation for Bataille to come on up: ‘After two minutes of conversation Félix was stuffing little balls of bread into Bataille’s ears; after 15 minutes, he was calling him imbéchille (‘imbecile’ with a lisp), a favourite term of endearment; after a week the two were inseparable.’ Le tout Paris seemed to react in the same way.

Nadar’s great love, his wife Ernestine —Barthes describes this as ‘one of the loveliest photographs in the world’

For someone called Félix, mind, he was not always lucky. In 1848 — he was ever drawn to romantic causes — he set off with 500 other volunteers to liberate Poland from the Russian (and Prussian, and Austrian) oppressor: ‘they never reached their destination, not a shot was fired, and Poland remained as oppressed as ever’. Undaunted, he set off for Prussia on a top-secret mission as a spy, under an assumed name. He toured six cities: ‘staying in comfortable hotels, he kept his eyes peeled for signs of war. There were none.’

Military action was not, it turned out, his forte. What he was brilliant at was — in a strikingly modern way, 100 years before it was much thought of — managing the business of celebrity. In the fervid media environment of the Second Republic, where new feuilletons and satirical journals seemed to open daily, Nadar plunged in — writing satirical squibs, a duff novel, and then… well, Begley’s witty chapter heading has it: ‘All Is Lost! Nadar Has Learned To Draw!’

He set up as a caricaturist. He was full of wheezes, at one point running a cartooning competition that he judged and in which he supplied all the entries. He won — though his citation was critical of the winning caricature’s clumsy execution. Still, his fame grew and soon he was employing assistants to bang out caricatures for the funny papers as fast as they could — all to go out under the Nadar logo. He knew the value of a brand. (A years-long feud with his younger brother, later, was to centre on the latter’s use of ‘Nadar jeune’ as a trademark.)

A characteristically ambitious project, at his height as a pen-and-ink man, was the Panthéon-Nadar: conceived as a quartet of enormous lithographs through which 1,200 luminaries of French cultural life would parade in caricature. It was so keenly anticipated, and so many thousands of francs spent advertising it, that word even reached the New-York Daily Times. He completed less than a quarter of the promised work before abandoning it.

His ambition was ever greater than his attention span. The chief of his many exasperated but indulgent mentors was Charles Philipon, a senior political caricaturist whose drawing of Louis-Philippe I as a pear had become a universal shorthand, like John Major’s Y-fronts. He wrote to Nadar at one point to complain that the ‘Revue trimestrielle […] for three years, has never appeared on time [… ] You will tell me you are very busy, I know, but I know above all that nothing is less true. You don’t work, so you’re not busy…’

When Nadar moved on, as he always did, it was to photography. This, after publicity, was his prime genius — and the two went together. He assembled his own pantheon, in a way. He befriended, and photographed, the literary greats of the day — capturing the last image of the lobster-walking maudit Gérard de Nerval, snapping Baudelaire and Théophile Gautier, as well as his heroine George Sand, and Victor Hugo (both alive and postmortem). And himself, of course — a lot.

So what was all that ballooning about? It’s hard to say — something, again, about attention spans perhaps — but the bug bit him. And, indeed, when Paris was encircled by the Prussians after Louis-Napoléon’s catastrophic prosecution of the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second Empire, it came in handy.

Nadar ascended in tethered balloons to survey the battlefield from above; and had the idea of sending free-floating balloons out of the siege to carry letters to the provisional government in Tours. ‘The world’s first air-mail,’ notes Begley. It was a propaganda coup; not that it did much to prevent the Prussians prevailing. (Begley, disappointingly, dismisses as too good to be true the story that the first balloon scattered Nadar’s business cards over the Prussian lines bearing compliments to the Kaiser.)

The oddest thing is that Nadar’s ballooning went hand in hand with his fervent belief that ballooning was a bad thing: he proselytised tirelessly for heavier-than-air (i.e. steerable) flying machines, and only went up in Le Géant (as the big one was called) in the hopes of raising money to invent the helicopter. Yet, writes Begley ruefully: ‘after all the tireless activity devoted to the enterprise, not a penny was ever raised to fund research into heavier-than-air flight’.

Well — to use Nadar’s motto: ‘Quand-même!’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in