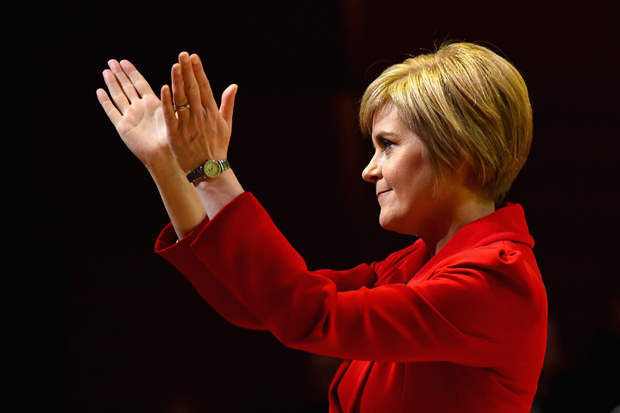

There is unlikely to be much of a legacy from Theresa May’s premiership, which could yet be truncated a short way into its second year. Yet one very good thing looks like coming out of it: the strengthening of the United Kingdom. The Union suddenly looks in better health than it has done for several years. Nicola Sturgeon did not quite scotch her dream of a second independence referendum this week, but in delaying the required legislation until the autumn of 2018 at the earliest she has bowed to the inevitable. She has been sent, as the Scottish national anthem says, homeward tae think again.

Meanwhile, the importance of Northern Ireland in Westminster has been enhanced. The deal between No. 10 and the DUP certainly looks like a grubby case of cash for votes, but it is also more explicit and honest than the kind of pork-barrel spending that is now routine in Westminster to soften up marginal constituencies. Many of those most critical of the deal with the DUP have spent the past few years denouncing ‘austerity’ and decrying the lack of investment in the provinces. The SNP seemed quite happy to lap up extra money offered to Scotland during the independence referendum.

The DUP’s leader in Westminster, Nigel Dodds, pointed out in the Commons this week that much of the opposition to the agreement is sheer hypocrisy. He even threatened to publish the correspondence between the DUP and Labour in 2010 and 2015, when the two parties discussed their own arrangements in the event of a hung parliament. Others, such as Caroline Lucas, co-leader of the Greens, have championed the idea of parties working together — except, that is, when the parties in question fail to conform to her idea of a ‘progressive alliance’. Surely it is a good thing that for the first time in recent history we have a government which has representation in all four nations of the United Kingdom. The Union needs to be strong to help our Brexit negotiations. No longer will the EU be able to weaken its opponent by driving a wedge between England and Scotland, as Nicola Sturgeon had hoped. There will be no halfway house for one part of the United Kingdom. The deal which emerges will have to work in all parts of the country. The DUP has already made one useful contribution by ensuring a higher priority for keeping open the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic.

The stronger the United Kingdom, the greater our leverage in Brexit negotiations and the stronger our position in the world afterwards. Part of the case for leaving was that the UK, as the world’s fifth largest economy, was big enough to demand its own bespoke deal with the EU on more favourable terms than those achieved by Norway and Switzerland. Moreover, the size of our economy serves to attract attention from nations outside Europe who want to forge alliances and bilateral trade deals with us. The threat of Scottish independence would weaken that advantage.

Two years ago, it seemed as if unionists had won the battle only to face the prospect of losing the war. The SNP’s near clean sweep of Scotland’s Westminster seats promoted a sense of inevitability about independence. Yet this political monoculture was short-lived, killed off before it could become established by the unexpected early election. No one can now present the Conservative and Unionist Party, to give it its full name, as an English party that is ruling Scotland from abroad. Indeed, were it not for the surge of support in Scottish Conservatism, Mrs May might not be Prime Minister at all.

With 13 Scottish seats in the Commons, the Scottish Conservatives cannot be ignored by Theresa May. Under Ruth Davidson’s inspiring leadership they have become a brand in themselves — at present a more successful one than the English version. One of Michael Gove’s first acts as Environment Secretary was to visit fishermen in his native Aberdeenshire and discuss their concerns about Brexit. His example ought to be followed: the Conservatives need to show in their everyday visits and consultations that the voice of Scots is being heard as loudly as the voice of Ulster.

The Prime Minister and her colleagues have no need to be apologetic about the deal with the DUP. On the contrary, they should make the most out of their poor election result by using it as an opportunity to command much broader national support — something the Conservatives allowed to slip away from the 1980s onwards.

Theresa May did not, of course, aim to put herself in this position. For her, the outcome of the election was a disaster that she, personally, inflicted. She will not be forgiven, by her party or country, for this misjudgment. Yet the unintended consequence, and something no one could have foreseen, is that the survival of the United Kingdom is looking more certain than it was a few weeks ago.

But as David Cameron demonstrated, Tory radicalism is possible in a hung parliament and — done properly — it can lead to Tory majorities.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in