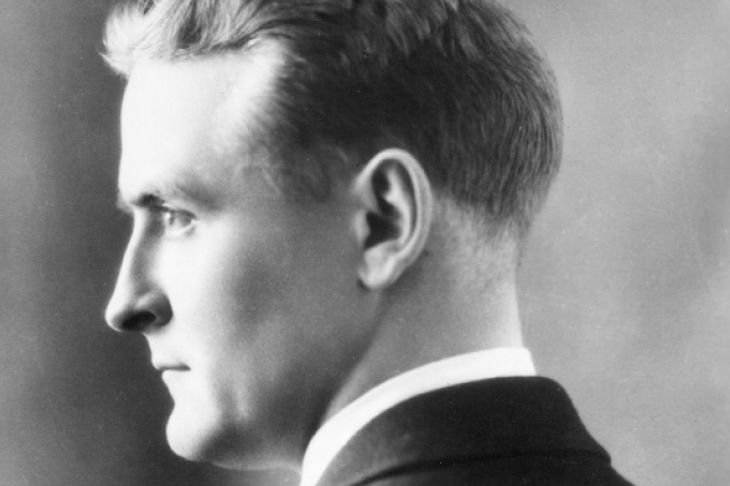

‘I do not like the idea of the biographical book,’ F. Scott Fitzgerald told his editor Max Perkins in 1936. Fitzgerald may not have liked it, but he certainly let himself in for it. As he wrote, with a grin, in 1937: ‘Most of what has happened to me is in my novels and short stories, that is, all the parts that could go into print.’

Of all the male American modernist writers with tragic lives, including Ernest Hemingway, Hart Crane and Eugene O’Neill, F. Scott Fitzgerald still serves to many people as the defining figure. A glittering success as a writer when he was just 23, Fitzgerald died 20 years later, still a young man, but with most of his works unread by the public, and his status as one of the most skilled and popular American writers unestablished.

His first novel, This Side of Paradise (1920), is the story of a bright young man who goes to Princeton and, upon graduation, finds the social and business world of New York made strangely incomprehensible to him in the aftermath of a great war he was — like Fitzgerald — too late to fight. The financial success Fitzgerald found in Paradise let him live his life as a full-time writer, and marry Zelda Sayre. a southern belle with red-gold curls from Montgomery, Alabama. The Fitzgeralds — their life together during the 1920s, and lives apart during the 1930s — proved compelling fodder for contemporary newspapers, and for novels, plays, and screenplays ever since.

So a major biography of Fitzgerald is long overdue. Zelda has been intensely chronicled in Nancy Milford’s Zelda (1970) and Sally Cline’s Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise (2002); but both of these are, to varying degrees, partisan polemics in which Scott is a failure, a villain and a plagiarist of Zelda’s writings. The truth of their relationship is much more compelling. In this book David S. Brown gets it absolutely right in terming them ‘partners’. The description, though, is in passing — as is so much, in what might have been a major biography, but is instead just a worthy introduction to Fitzgerald for new readers.

Brown, a historian, intends to make one of Fitzgerald too. He is right to think of Fitzgerald as a man with an interest in not only American but world history. But to treat Fitzgerald as a ‘cultural historian, the annalist as novelist’ is to disorder him. Fitzgerald was a novelist first, and his sense of history and use of it in his writings comes second, always, to his imagination. Scolding Ernest Hemingway in June 1926, in his extensive edits to The Sun Also Rises, Fitzgerald reminded him: ‘The fact that it may be “true” is utterly immaterial’; and he affirmed ‘the superiority (the preferability) of the imagined to the seen, not to say the merely recounted’.

Brown makes the good point that Fitzgerald’s sense of history was ‘at its core sentimental, nostalgic and conservative’. Of Fitzgerald’s Maryland heritage, he writes: ‘The pretensions of an established Maryland lineage cushioned the reality that he remained throughout his life a restless and somewhat transitory figure.’ And he quotes the spot-on view of Fitzgerald’s early biographer Andrew Turnbull that

History for Fitzgerald was chiefly colour, personalities and romance. It was Jackson’s Valley Campaign; it was The Gallant Pelham rapid-firing — one cannon against 16 — at Gettysburg.

Yet Brown pushes no further.

Fitzgerald did not want to live his life restlessly and in transition. He had hoped to make his family’s home in Maryland; Zelda’s illness changed all that. When the Finneys — old Princeton friends who provided a home for the Fitzgeralds’ daughter Scottie while her mother was hospitalised — arranged for Scottie to appear at a local debutante ball, Fitzgerald wrote them a heart-wrenching thank-you letter on her behalf that speaks, too, for himself: ‘So desperate is her love for Baltimore and her determination to think of it as home. I suppose children simply aren’t nomads — their hearts must be somewhere.’

In his close readings of Fitzgerald’s short stories and novels, Brown focuses on contemporary circumstances. He calls the early stories ‘May Day’, ‘The Diamond as Big as the Ritz’ and ‘Bernice Bobs Her Hair’ ‘a powerful triumvirate’ and ‘surprisingly effective meditations on cultural and economic change’ — but those cultural and economic changes are left undefined. Worse, he sweepingly generalises from Fitzgerald’s literary creations about reality at the time of their writing: ‘Viewed expansively, Bernice’s story is the story of a growing number of young American women in the 1920s.’ This is the thus-we-see school of history. But when Brown does discuss specific historical events during Fitzgerald’s life, and how they reflect in his writing — something he too infrequently does — he helps us see where Fitzgerald is coming from. Still, the fact that a gifted writer possessed of a rich imagination was conscious of his cultural context is hardly surprising.

Brown cites a number of influences on Fitzgerald, for better and for worse. He proposes that, in light of This Side of Paradise,

we might … consider placing Fitzgerald in a line of distinguished Progressive-era (1900–1920) intellectuals, running from the radical economist Thorstein Veblen to the left-leaning social critic Randolph Bourne to the right-leaning cultural critic H.L. Mencken.

We might, but then again we might not. Paradise Lost strains to contain such correspondences.

Brown sees in the famous last page of Gatsby an echo of the historian Frederick Jackson Turner’s essay on the ‘westward movement’ and the progressive line of America’s frontier. This misses the regretful nostalgia at the end of Gatsby. In 1925, America’s frontiers were no more. The Native American chieftains who had marked its last line were dead by the turn of the century, or had joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show — safe and sanitised.

He concludes Paradise Lost with a brief, poignant coda to Zelda, who outlived her husband by just over seven years, and a bare summary, ‘Life After Death’, that praises Budd Schulberg and Sheila Graham above Arthur Mizener, Edmund Wilson and even Scottie Fitzgerald as the people who brought ‘a flawed if fully human Fitzgerald’ to readers in the decade after he died.

The last lines of Paradise Lost will be familiar: ‘So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.’ Hypotheses and agendas entirely aside, Fitzgerald himself is any biographer’s best help. His words are what keep writers in so many genres coming back to him. After he turned 40, Fitzgerald wanted to write his own official autobiography, but put it off until his ‘load of debt’ was lifted. It never was.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in