David Hepworth is such a clever writer — not just clever in the things he writes, but in the way he has conducted his career. A decade older than me, he too started out at the New Musical Express; but he went on to take Smash Hits to glory as editor, to launch Just Seventeen, Empire, Mojo and Heat, and remains the only person to have won both the PPA’s writer of the year and editor of the year awards.

His previous book, Never a Dull Moment: 1971, The Year that Rock Exploded, was a great critical and commercial success. And to show how adept he is, he has now gone from examining a single year in forensic detail to assembling 40 vignettes, from 1955 to 1995, exploring defining moments in the lives of important rock stars: for example, ‘24 June 1970: Rock god embraces the occult’ (Jim Morrison); ‘27 January 1984: A superstar on fire’ (Michael Jackson); ‘7 June 1993: Career suicide’ (Prince) and so on. He concludes that rock stars no longer exist, killed off by a combination of hip hop, stage schools and social media. But, as you can see from the chapter titles, he’s anything but a why-oh-whiner concerning the state of rock’s rich tapestry. ‘Jaunty’ says it best. You can almost hear him exclaiming ‘Crikey!’ at key moments of epicness.

Hepworth’s theory of supply and demand — and how the way the internet-driven former outstripping the latter led to familiarity breeding a certain cavalierness on the part of fan towards idol — is illustrated in the most poignant sketch. Here a teenage Keith Richards and Mick Jagger, separated by the class system since their primary school days, meet again by accident at Dartford railway station:

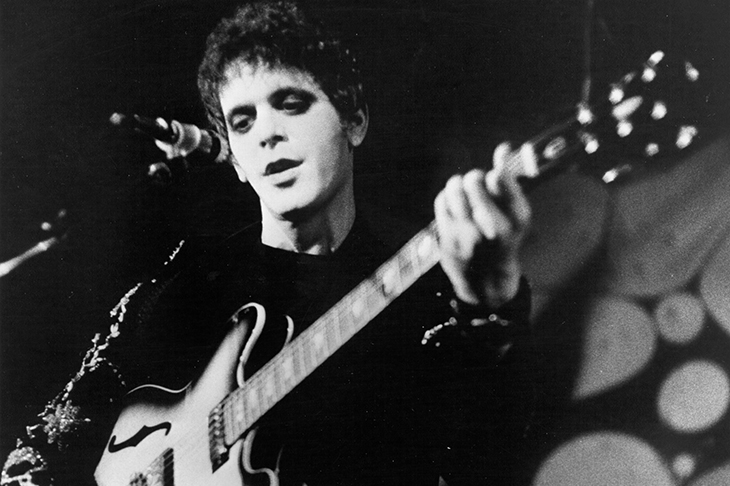

What united them was stronger than what divided them. Mick was carrying two albums under his arm — Chuck Berry’s Rockin’ at the Hops and The Best of Muddy Waters…. Keith was lugging his hollow-bodied Epiphone guitar. The carrying of such items in a public place in the year 1961 was like a cry for help. They weren’t going anywhere in particular. They were probably carrying these items to show that they had them. The two struck up a conversation. It was inconceivable they wouldn’t.

You don’t have to be a grumpy old nostalgic to think that kids today, glued to their screens, might easily walk right past a kindred spirit in a similar situation — just as they’ve come to swerve sex and drugs for the solitary pleasures of the smartphone.

But of course the fall of the rock star is not all gloom and doom: it’s not awfully good for human beings to worship other human beings, either as love objects or love slaves. In such situations, it’s not even clear whether we were actually adoring another person or conducting a scenic-route romance with an idealised version of ourselves. My husband, with admirable masculine brusqueness, has noted a phenomenon he calls ‘tearleading’ — that of ululating groups of people getting together to competitively mourn dead celebs on social media — which may well have as much to do with their own sorrow that their lives have not matched up to their teenage dreams as with the deceased.

‘The age of the rock star, like the age of the cowboy, has passed. The idea of the rock star, like the idea of the cowboy, lives on.’ Uncommon People is a gorgeous read, celebratory and bittersweet, both pep rally and memorial, throbbing with insight and incident. It made me think of Jennifer Egan’s great novel A Visit From the Goon Squad — all those lives lived separately but impacting collectively. Hepworth’s is one of those rare books I could hardly stand to pick up, as it repeatedly made me feel quite overexcited, with that strange, vertiginous, oceanic feeling I get being driven fast from slip roads onto motorways, everyone alone yet united, rushing together like corpuscles in a bloodstream.

And on a purely selfish level, it made me fervently feel that just as I was lucky to become a journalist when I did, helping myself to the huge amounts of cash and kudos just waiting to be pocketed by any little counter-jumper from the popular music magazines, so bliss was it to be a horny adolescent when real rock stars roamed the earth: tyrannosaurs in top hats compared to the bumbling brachiosaurs in backwards baseball caps which pass for pop idols today.

All in all, not having to be young in an age when Ed Sheeran and Adele are the Adam and Eve of Ikea authenticity is a great consolation prize for becoming middle-aged.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in