The concert began with a flourish and a honk. Well, of course it did. Telemann wrote his last Ouverture-Suite in F major for the Landgrave of Darmstadt. The Landgrave loved hunting, and in the 18th century hunting meant horns. And horns mean honks. If you’ve ever played the horn — applied 12 feet of coiled metal tube to your face and tried, through a combination of lip muscles and willpower, to make the damn thing sing — you’ll know that no amount of hoping, praying or practice can prevent the occasional squawk. The two excellent players in Florilegium’s concert at St John’s Smith Square, moreover, were using 18th century-style horns — without the valves and additional plumbing that render the modern beast just about controllable. With a whole evening of Telemann ahead, they got their honk out of the way early, and it sounded glorious.

Because — let’s not pretend otherwise —Telemann does need a bit of roughing-up. Two-hundred-and-fifty years after his death, his reputation is still that of a worthy, over-prolific purveyor of musical muesli. But how does that square with the bewigged old gent with lively eyes who smiles from the engraved portrait in the programme book? Dig deeper, and he comes alive: his kindness to younger musicians, his love of tulips, the courage with which he bore the early death of one wife and the ruinous cruelty of a second, and above all the little miracle that this anniversary concert — part of the London Festival of Baroque Music — set out to celebrate. ‘Baroque at the Edge’ was the festival’s theme, and in chronological terms alone it was on the money. The Ouverture-Suite dates from 1766, by which time Mozart had written his first symphony and Haydn was already working for the Esterhazys.

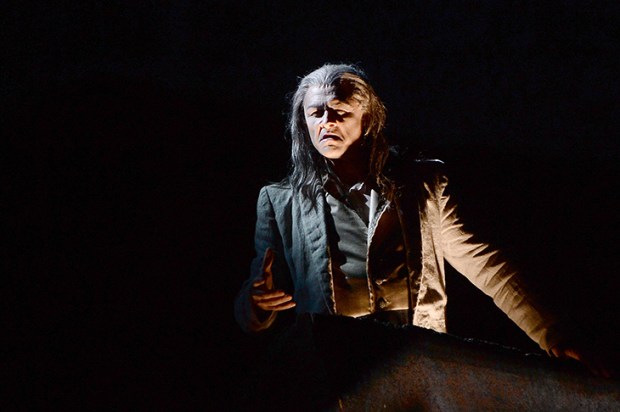

And it’s as though Telemann knew it. He was 85 when he composed the Ouverture-Suite, and only a year younger when he wrote the cantata Ino. But there’s no nostalgia here: instead, a vital, startlingly on-trend creative energy that makes the dance movements of the suite swing like the scherzos that Haydn wouldn’t invent for another 15 years, and tips you head-first into the action of Ino. Imagine a one-woman Gluck opera. The soprano Elin Manahan Thomas sang the part of the ancient Greek queen who, pursued by a vengeful Juno, leaps into the sea where (luckily enough) Neptune takes a shine to her. She went at it head-on, in light, bell-like peals of coloratura that emphasised the freshness and drama of Telemann’s writing — dancing helter-skelter over some bracingly crunchy harmonies. I just wish the strings of Florilegium had been able to project a bit more, well, edge — though to be fair, the muzzy St John’s acoustic didn’t help.

So thank the gods of Olympus for those lords of misrule, the baroque horns: playing with increasing precision as the evening went on, but never tempering that exhilarating bite, or the jarring natural overtones that make them sound like a voice of creation itself — ancient, untamed and potentially dangerous. Telemann casts them as Tritons in Ino, and the old Hamburger knew precisely what he was doing. The concert as a whole reminded me of Charles Burney’s comment on Haydn’s late quartets – ‘the productions, not of a sublime genius who has written so much and so well already, but of one of highly-cultivated talents, who had expended none of his fire before.’

But then, it’s always good to have your preconceptions challenged. The Guangzhou Symphony Orchestra has been touring the UK under its music director Long Yu. He’s a commanding figure on China’s orchestral scene, sometimes referred to as the ‘Chinese Karajan’ — and not in a good way, though he’s evidently a formidable orchestra-trainer. People who spend more time listening to old recordings than living musicians sometimes assert that today’s orchestras all sound the same, but the GSO has a wholly distinctive character: clear, bright, with full-throated woodwinds and a string section that can pour out sheets of fluid, glossy tone, heard to impressive effect in Yu’s metronomically precise accounts of Britten’s Four Sea Interludes and Stravinsky’s 1919 Firebird suite.

In between came two recent GSO commissions, Ye Xiaogang’s Ravel-like Guangdong Music Suite and a double concerto for sheng and cello by Lin Zhao. Both were immediately attractive, and it’s not every day that you get to hear a sheng played live by an artist as capable as the soloist here, Lei Jia. It’s an extraordinary, steampunk-looking thing — a gleaming black and silver miniature pipe organ, played through a mouthpiece and producing a sound rather like that 1970s classroom favourite, the melodica. Zhao surrounded it with lush, moody textures that reinforced my deepening suspicion that Hollywood film music, from Korngold through to James Horner, will turn out to have been the western classical tradition’s most influential legacy in the 21st century.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in