Over the long weekend I read a couple of bildungs-romans; one a revisit after many years, the other a recent work. In Hemingway’s words, A Moveable Feast was about living in Paris ‘when we were very poor and very happy’. The poverty was relative. Hemingway did occasionally have to skip lunch, but there was always enough to drink, even if some of it, from Corsica or Cahors — rough in those days — was better mixed with water. Fishermen still plied the banks of the Seine. Simple restaurants sold the catch, delicious with Muscadet, and our author does not mention ill effects.

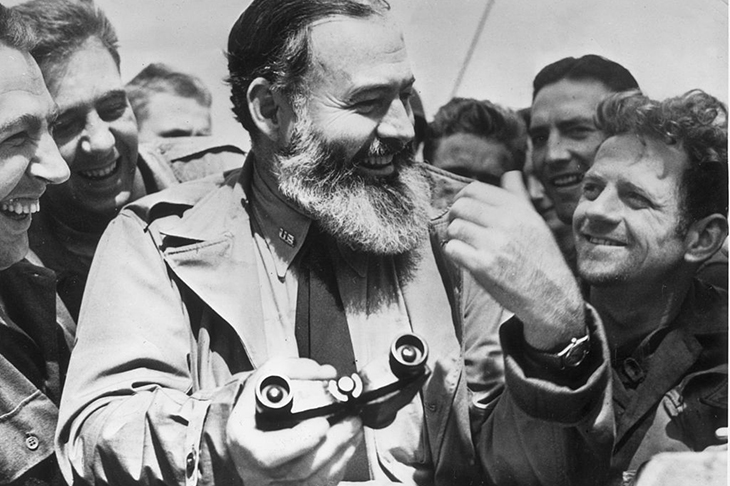

Nor does he inflict any on his readers. Yet there is an obvious question. How good a writer was Hemingway? Although one forgives him a great deal because he exalted bullfighting, his style is basic, deliberately so, with lots of ‘ands’. There is plenty of vin ordinaire; hardly a sentence worthy of long savouring. At 20, I devoured him. Now that I am slightly older, he is on the rereading list. Is he much more than John Buchan with a Nobel prize? Not that I would dissuade anyone from A Moveable Feast. One would love to have visited Paris in the 1920s. Hemingway evokes a pre-lapsarian existence with a son, a cat, an adorable wife and a rarely shaken confidence in his literary gifts: bliss was it in that dawn to be alive. Yet he was about to destroy that stability and fling himself into tempest after tempest. Perhaps that was necessary for his bildung to reach fulfilment. But there is also sadness: a anticipatory sense of ultimate loss.

There is loss and sadness in the second book, but only in alloy. Rory Stewart is one of the most talented men of our era. The Marches takes us from Rory’s constituency to his family house in an attempt to understand the bloody history of the Scottish borders, from the Roman Empire to the British one. By concentrating on this most disputed region of our mainland, he is trying to root contemporary politics in long history, and make sense of both. It is also an engagement with Rory’s father, who had a wonderful life. His career was based on Empire and service; his creed on duty, stoicism, and a never long-absent sense of fun. Freud said that a man ought to be able to love and to work. Brian Stewart might have been shocked to learn it, but he was a successful Freudian.

In walks with his father and longer solitary excursions, Rory was grappling with modern Scotland. The quest is fascinating even if the answers are elusive. Brian assumed that because their history had been shaped by conflict, the Scots were a more interesting people than the English. But he could not understand the call for a separate Scottish state. Until his war was ended by a serious wound in Normandy, he was in the Black Watch. The men in his battalion wore kilts and the Red Hackle. He instructed them in Highland dancing. Yet to a man, they were Geordies, recruited in Newcastle. To him and presumably them, Scottishness and Englishness found fulfilment in Britishness, the conclusion of their bildung.

Let us hope Rory will devote a great proportion of his political energies to ensuring that future generations can enjoy Britishness in the footsteps of those Tyneside Highlanders. If so, he faces a daunting task. Just as well the Stewarts are not easy men to daunt — no sign of his succumbing to Hemingwayesque despair.

On Sunday, the wine was so good that everyone put up with me banging on about bildungs. We had a Bâtard-Montrachet ’08 from Pierre Bourée, only just ready. Everyone is terrified about their white Burgundy treasures falling to oxidisation; that would be an excuse for despair. We moved on to a Domaine de Chevalier ’04 — able to stand up to the Bâtard — and concluded that wine is its own bildung.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in