Min Kym is a violinist, but if you Google her name you won’t find sound-clips or concert reviews, touring schedules or YouTube videos. What you’ll get are news reports. Because one evening in 2010, when Kym was waiting for a train at Euston Station, her 300-year-old Stradivarius violin was stolen. Almost three years later it was recovered, and an ‘elated’ Kym was back in the papers, but the happy ending was more editorial convenience than truth. Now Kym herself has written a memoir in an attempt to explain what she really lost that day, and the impossibility of ever truly recovering it.

Gone is an awkward book. The style shouts thriller — a relentless drumbeat of staccato sentences and long-trailed expectation — but the content is the discursive, drifting stuff of memoir. Being a child prodigy is a life that straddles genres, flirting with technical manual, self-help book and YA fiction on its journey to adult autobiography, but it doesn’t make for the easiest of reads, especially in first-time hands. Kym’s violin, as she repeatedly tells us, is her voice, but there’s a sense here of the author trying on another for size, one that — as yet — can’t manage much more than a whisper.

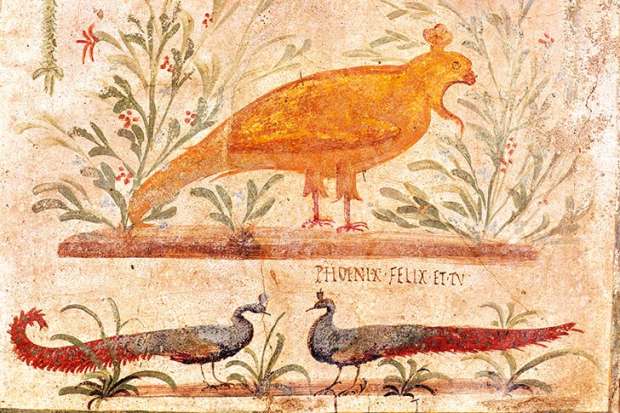

‘A Life Unstrung’: the subtitle contains a potent image, but one that, like so much else in this memoir, doesn’t really belong to its author. In shaping the book’s central idea, an elision between player and instrument, woman and object, she borrows cultural rhetoric that comes ready-loaded. When we read that ‘The violin was part of me and I part of the violin’, we think of Man Ray’s ‘Le Violon d’Ingres’ — the woman with a violin’s F holes in her back, the instrument on which the photographer plays his visual music; or of Magritte’s ‘La Decouverte’ — her flesh transforming into wood under the artist’s gaze; or even perhaps of the ghastly cover art for R. Kelly’s Black Panties album, in which the singer ‘plays’ a naked woman with a cello bow. We struggle to see clearly through to the timid pencil strokes of Kym’s own self-portrait.

Because while this is a book about music, about the life of a child prodigy, a violin found and lost, it’s as much a book about being a woman. The two narratives are indivisible. Again and again as Kym tells her story, her prodigious talent becomes a vehicle for men to express themselves: something for teachers, dealers, conductors, fathers and lovers to appropriate and claim as their own. ‘She is a little diamond, and I want to be the one to polish her,’ says her professor — the first of many to see himself reflected back in her brilliance.

And this is where things really do come into focus. Kym’s prose struggles under the weight of introspection, but supports her surrounding characters with neat efficiency. The puppyish young lover whose affection becomes stifling control; the expert-by-endeavour who cannot connect with the instinctive prodigy; Kym’s Korean family, who must learn to adapt to their unusual daughter — all are swiftly, skilfully drawn. It’s the book of a woman who has grown up watching rather than speaking out, translating action into thought rather than the reverse. ‘But I wasn’t strong enough’, is a recurring refrain — a weakness born of training and habit as much as the anorexia the author reveals in the closing pages — and one whose pliant passivity is only partly vanquished here.

There’s a real appetite for books about the singularity of genius, and while Gone goes some way towards feeding that, returning three times to the question of what it is to be a prodigy, delivering darker answers with each iteration — ‘It’s a means to another’s end. There’s a price to pay, and that price is you’ — it is surprisingly light on music. We get the compulsion of playing, the ease of it, the urgency of it, but comparatively little about the repertoire that is generated by it. Kym could be a mathematician or a chess champion and the book would read much the same.

Perhaps that’s the point; to be a prodigy is to be given a gift, not a choice, and to accept it is to become a curator, not necessarily an artist. Kym’s interest in music is that of the golfer’s in the courses he plays — functional, unquestioning. Her real passion is reserved for fellow violinists, Heifetz in particular, whose style she describes in language suddenly agile and precise.

And what of the violin itself, the 1696 Stradivarius eventually restored to Kym, only to be torn away again, sold to appease the insurance company and dealers hungry to capitalise on its new notoriety? It remains an elusive symbol — a vessel, whose hollow body becomes the space into which Kym pours herself, conceals herself, reshaping her own embattled body in its image. ‘You’re the artist, not the violin,’ says Kym’s friend. But she’s not so sure, and by the end of this frustrating, intermittently fascinating book, neither are we.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in