Are you a deathist? A deathist is someone who accepts the fact of death, who thinks the ongoing massacre of us all by ageing is not a scandal. A deathist even insists that death is valuable: that the only thing that gives life meaning is the fact that it ends — an idea not necessarily embraced by someone about to be murdered on video by an Isis fanatic.

But what is the alternative? There has never been one, which is why until recently no one needed to coin the term ‘deathist’. But now many tech entrepreneurs and scientists take a different view: death, they say, is simply an engineering challenge. Biotechnology should, in principle, be able to reverse the wear-and-tear on cellular machinery in our bodies and keep us in our prime indefinitely, barring violent accident. Consider how many lives this would save. If you think such research should not be pursued, then you are a throwback, a deathist, a morose Luddite thanatophile.

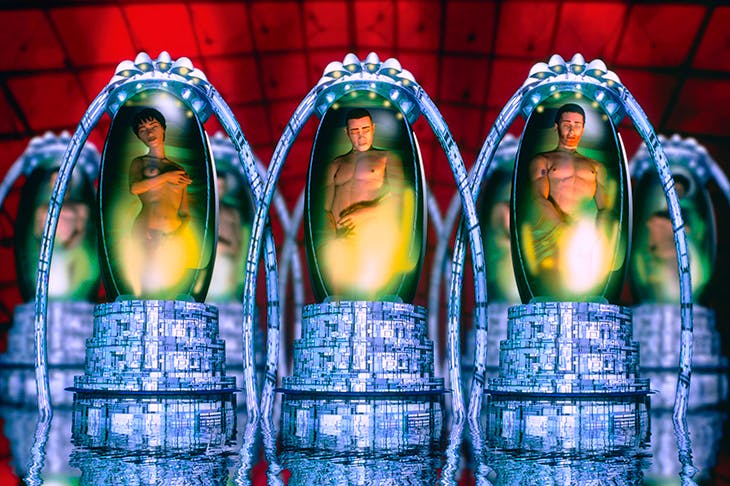

Anti-deathism is one of the main strands of a set of sci-fi dreams that come under the umbrella term ‘transhumanism’, the subject of the Irish literary critic Mark O’Connell’s engaging tour. He visits a cryonics facility in the desert outside Phoenix, where customers have paid to have their whole bodies or just their heads (called, Greekly, ‘cephalons’ in the facility’s distancing jargon) preserved by freezing, in the hope that science will one day figure out how to revive them. He goes to a robotics fair where the audience gasps at humanoid robots that can operate door handles or ‘egress’ successfully from a car. He hangs out with a gang of ‘grinder’ cyborgs, that like to implant boxes of electronics under their skin in order to, say, be able to sense the presence of an electromagnetic field. He interviews people working on the idea of ‘uploading’ human minds to computers, and those — like the philosopher Nick Bostrom — who fear that one day soon they, and we, might be killed by an omnipotent artificial intelligence of our own creation.

This is all related in a sort of wryly melancholy version of gonzo narrative non-fiction, structured in the simple ‘What I Did Next For My Research’ style. Think a more overtly erudite version of Jon Ronson. As with that writer, you do occasionally feel that O’Connell is expending energy on a less interesting figure simply because they provide so much freakish colour. Some of his transhumanist subjects are pitiful (the virginal man who looks forward to ‘sexbots’) but others — for instance, the American scientist Laura Deming, who focuses on ‘life extension’ research — are extremely intelligent and persuasive. Overall, the book is thoughtful, modestly unsure of its own opinion, and often disarmingly funny. (Cryogenically frozen brains are left in their skulls, O’Connell explains, because ‘technically, it is kind of a hassle to remove the thing entirely’.)

The author is especially alert to the assumptions encoded within tech-utopian rhetoric — for example, the habit of saying that we should ‘solve’ death:

The word ‘solve’ seemed to me to encapsulate the Silicon Valley ideology whereby all of life could neatly be divided into problems and solutions — solutions that always took the form of some or other application

of technology.

And the very prefix ‘trans-’ in the word transhumanism expresses, for some, a forlorn desire for spiritual transcendence of mere meat. As one cyborg tinkerer explains to the author:

Ask anyone who’s transgender. They’ll tell you they’re trapped in the wrong body. But me, I’m trapped in the wrong body because I’m trapped in a body. All bodies are the wrong body.

The apparent paradox, then, is that so many transhumanists, while bent on defeating or ‘solving’ death, also seem rather, well, misanthropic. To be transhumanist is on some level also to be anti-humanist: people tell O’Connell what contemptible ‘monkeys’ current humans are, how disgusting it is that they are doing all this breeding, and how they’d rather be machine-based consciousnesses exploring the vastness of space. But when it comes down to it, you might think there is not all that much to distinguish this, as a consummation devoutly to be wished, from good old-fashioned death.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in