Michelangelo’s Tomb for Pope Julius II: Genesis and Genius

edited by Christoph Luitpold Frommel, translated by A. Lawrence Jenkens JrYale, £50, pp. 368

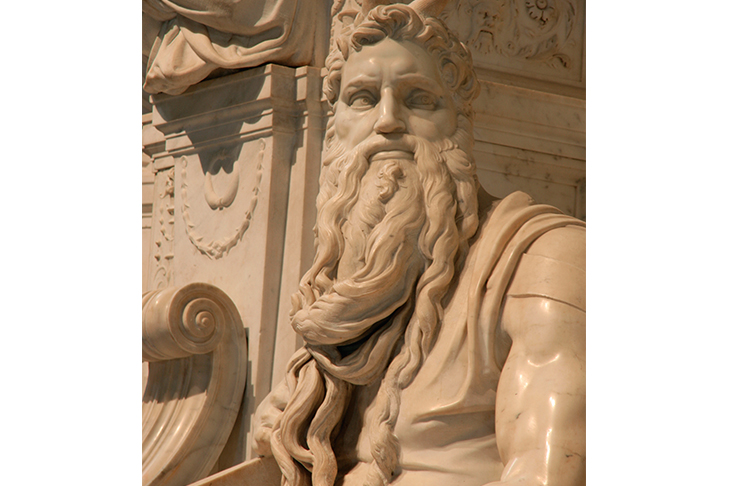

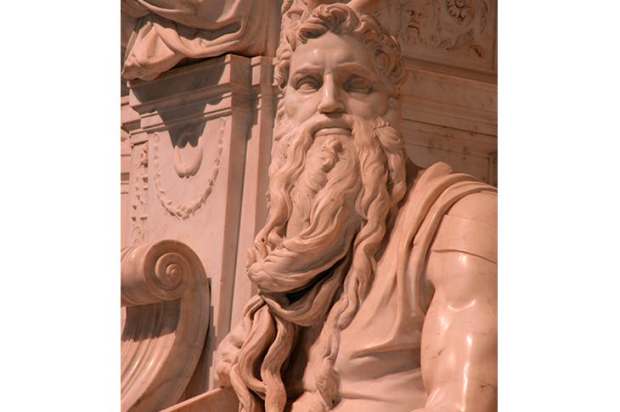

‘How often’, wrote Sigmund Freud in 1914, ‘have I mounted the steep steps from the unlovely Corso Cavour to the lonely piazza where the church stands, and have essayed to support the angry scorn of the heroic glance.’ The gaze that the founder of psychoanalysis struggled to withstand belonged to Michelangelo’s Moses, centrepiece of the tomb of Julius II in the basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli.

Michelangelo’s Moses has indeed a look of formidable authority. The prophet possesses, in addition, the physique of a body-builder, a beard that cascades like Niagara Falls and a pair of knees for which the best adjective is also ‘heroic’. Yet, despite its power, this statue was — for its creator — just one element in an agonising, slow-motion disaster. In the life of Michelangelo by Condivi — something close to a modern ‘as-told-to’ biography — this is described as ‘the tragedy of the tomb’. It was just about the worst case of project overrun in art history.

When first planned in 1505, the sepulchre was intended to dominate the choir of the newly rebuilt St Peter’s. It was to be free-standing — almost a building in its own right — arrayed with some 40 sculptures, including prophets, sibyls, Moses, St Paul and beautiful, naked young men: a glorious memorial not only to Julius II, but also to the genius who carved it.

In this superbly illustrated and meticulously documented volume, Christoph Luitpold Frommel analyses what followed. Within a year, to Michelangelo’s fury, Julius had tired of slow progress and rising costs. The sculptor fled to Florence, was forced to return to papal service and eventually diverted — against his will — into painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

After Julius died in 1513 Michelangelo carried on with the tomb, but then his attention shifted to another scheme — then another, and another. Decades went by. The Reformation split Christianity, Rome was sacked — and still the tomb remained unfinished.

Too many powerful people wanted Michelangelo to work on their own grands projets. On being told that the artist could not enter his service as he was under contract to execute the tomb, for example, Pope Paul III exclaimed: ‘Where is this contract? I will tear it up!’ On the other hand, Julius’s heirs remained too forceful for the whole thing to be dropped. It was particularly hard to ignore his alarmingly irascible nephew — Francesco Maria della Rovere, Duke of Urbino — who once ran a cardinal through with a pike after a brisk exchange of views.

Consequently, the project went through a dizzyingly complicated series of revised contracts and modified designs — and with each alteration, it dwindled. A number of masterpieces were intended for it — including the two Slaves in the Louvre — only to be discarded as Michelangelo’s ideas changed. By the time the tomb was finally installed, 40 years after this marathon began, its site had been moved to a different, far less prominent, church and the number of sculptures included had fallen to seven. Even after it was finished, the sorry business continued to trouble Michelangelo.

No one — including the artist — has ever been sure what to make of the ultimate result. In Condivi’s authorised biography it is described as ‘botched’ — but still the most impressive tomb in Rome (which may still be true, although Bernini later produced some strong competition).

The truth was that Michelangelo’s style changed radically in the aeons during which he was at work on it. As a result the architecture of the upper part is in his late style, while the lower section reflects his 15th-century roots. Moses is completely out of scale with the two female figures — representing the active and contemplative life — that flank him on either side. The other ill-assorted sculptures are largely the work of assistants (except — the authors claim — the recumbent effigy of Julius himself).

The essays by Frommel and the other contributors are full of fresh insights, many garnered from a restoration in the 1990s. But perhaps the most valuable aspect of this publication is the array of sumptuous photographs by Andrea Jemolo. These allow one to appreciate the tomb, detail by detail, for what it is: an assortment of fragments salvaged from one of the most ambitious sculptural projects ever conceived.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in