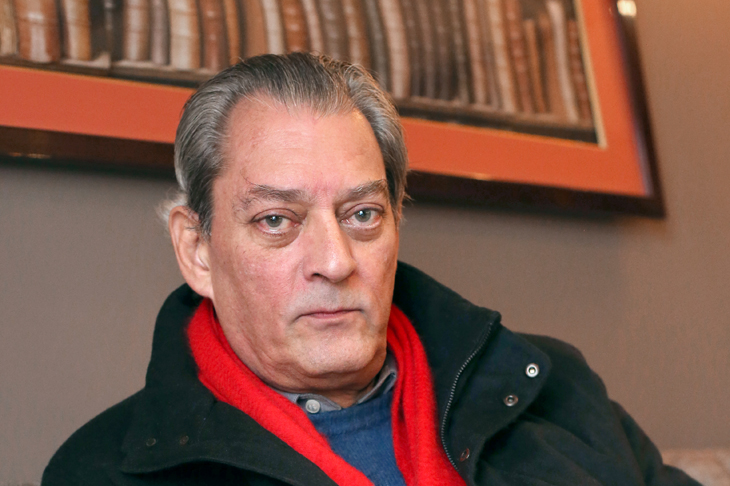

After a long struggle to receive mainstream publication, Paul Auster’s first few novels were a genuinely significant contribution to American letters, his patented mix of postmodernism, deadpan comedy and metatextual homage to Kafka, Hamsun, Melville and Hawthorne so singular it invited parody. Among these books, The New York Trilogy and The Music of Chance seem likely to last many years from now.

But the second half of his career has proved more problematic. Seemingly tiring of his own shtick, he spent a long time dismantling what made him great, sometimes to powerful effect (Oracle Night), but more usually in a way that seemed designed deliberately to test his biggest fans. His writer protagonists used to be detectives manqué, trapped in compelling noir narratives; in later novels they’re more likely to fret about their membership of PEN. Now, however, he has produced a novel as likely to cement his reputation among the American greats as Don DeLillo’s Underworld (Auster’s friend and arguably the writer he most resembles).

The concept of 4 3 2 1 is not original. Auster is far from the first author to take inspiration from Robert Frost’s poem ‘The Road Not Taken’ to explore the different directions a protagonist’s life might take. In the past few years alone, this conceit has powered Lionel Shriver’s The Post-Birthday World, Kate Atkinson’s Life after Life and Laura Barnett’s The Versions of Us. It is also commonly used in film, TV, science-fiction and comics, where the multiverse is a common get-out clause to reverse a protagonist’s demise or reboot a flagging narrative.

But Auster ups the stakes in two ways: first, he gives his protagonist, Archibald Isaac Ferguson, four alternate lives; and second, he depicts these alternate existences with such creative energy that it’s a delight rather than a chore to switch between narratives, experiencing childhood, first love and creative ambition over and over again.

Towards the end of the novel, Auster takes a swipe at Updike and Bellow, but his real enemy is middlebrow realist novelists who shy away from the eccentric. What elevates this novel is not the conceit of the road not taken, but the fact that all roads offered are so perilous. Although the four iterations of Ferguson have relatively straightforward ambitions — all they want is to write, and to find suitable sexual partners — they are forever surrounded by death and disaster.

Only one Ferguson will make it to the end of the novel, and there is a thrilling sense throughout that anything can happen at any time. The downside of this is that Auster finds it perfectly acceptable to devote over 13 pages to a dopey piece of juvenilia that one of his Fergusons writes about a sentient pair of shoes. The upside is that Auster gives us the epic novel that even his greatest fans might have assumed beyond him. Among American novelists only DeLillo and Roth have produced late work of this quality. To put it in terms Auster’s protagonists would relish, 4 3 2 1 is an epic home-run.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in