Athens

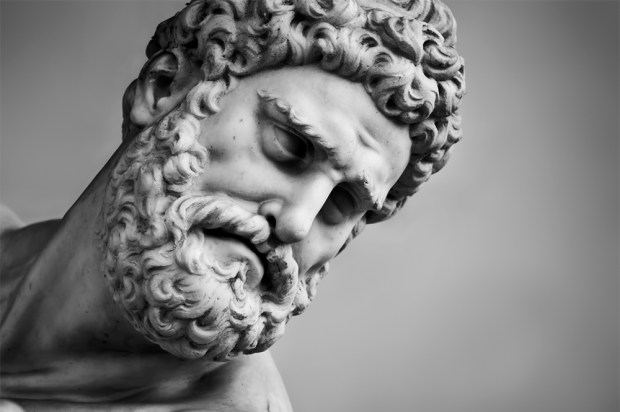

I can only ask sardonically: was it worth it? Executed after unspeakable torture without giving anything away — and for what? Fat, avaricious and very rich Davos Man? Or those ignorant, self-indulgent, cowardly little twerps who demand ‘safe spaces in universities’? Was it worth dying for the crooks of Brussels and the Angela Merkels of this world? Poor, heroic and stoic Kostas Perrikos, whose statue stands on Gladstone Street in Athens, died a hero, and for what?

Let’s begin with heroes. They are very different from peacocks. They don’t strut or take selfies, and they are mostly sotto voce. They don’t create whirlwinds and are a PR huckster’s nightmare. I’ve often wondered what makes a person’s life, or his or her individual actions, heroic to the point where their legacy stands the test of time. What follows will not explain what makes men and women act heroically, it will just recount history.

I was recently contacted by the Greek writer Constantine Lagos, who is writing the biography of the Greek air force officer Kostas Perrikos, whom I mention briefly in my book Nothing To Declare, published some 25 years ago. In brief: I was in an Athenian nightclub in the summer of 1965, or around that time, when someone I didn’t know sat down at my table. He was unaware that it was reserved, so I told the maître d’ to point this out. We were both very polite but when he heard my name he said something under his breath, so I asked for his name. ‘Perrikos’ was all he said and bade me goodbye.

I later asked my father if he knew the name Perrikos, and he almost jumped out of his skin. ‘Do I know it? I owe him my life,’ he said. As it turned out, the details were sketchy because the operation in question was on a need-to-know basis. According to my dad, he provided the dynamite and details of Espo, the ‘traitors’ headquarters that contained the names of Greek youths likely to be turned to the Axis cause, as well as those resisting the occupation. He met Perrikos only once during that meeting.

Perrikos entered the Espo headquarters with two other men and a woman, Ioulia Bimba, who apparently planted the stuff while Perrikos drew attention to himself. The explosion killed and wounded close to 40 collaborators and six German officers. All records were destroyed.

This was in September 1942, and Perrikos and Ioulia were quickly rounded up. My father’s opinion was that communists gave him away as he was a man of the left but no Stalin stooge. Perrikos never broke under torture and during his trial assumed all responsibility. Sentenced to death, he wrote his son Dimitris a last letter that apparently brought tears to the eyes of the German executioners. He wrote that Dimitris should not hate the Germans because one day they and the Greeks would be allies — some allies — and that he (Kostas) had done his duty as a Greek officer. He was executed the next day in Kaisariani, but was first saluted by all the German officers present. His last words were, ‘I have done my duty as an officer, now you must do yours.’

Ioulia’s fate was far worse. Sent to Dachau, she endured hell for another two years before being beheaded. Kostas Perrikos’s bust was finally raised on Gladstone Street in 1987. His son Dimitris was a brilliant student and was sought after as a chemist by the multinationals. Instead, he chose to join the UN and was among those who reported on Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction. He famously used the words that there was no smoking gun to be found. Dimitris Perrikos was the man I had a brief conversation with in the Athenian nightclub.

Constantine Lagos was planning to get Dimitris Perrikos and me together as there are very few records left about the blowing up of the Espo building. The irony of it is that as Dimitris was exposing the neocon con job regarding weapons of mass destruction, I was starting a magazine to expose that very con job perpetrated by George W. Bush, Dick Cheney and the neocon establishment in Washington that had smelled out a true blue dumbo in George W, one that could be manipulated at will.

Alas, we never met. Dimitris Perrikos died in Vienna two weeks before last Christmas. Which brings me back to heroes like his father and the question as to whether his sacrifice was worth it. Obviously the answer has to be that yes, it was, otherwise we would all be like those cowardly students who demand safe spaces. But it still makes one wonder. Would Kostas Perrikos have endured what he did in order to see his country overrun by sub-Saharans and Afghans because Angela Merkel felt it was good form to take in allcomers? Would he have gladly given his life so that Brussels stooges could order us around? Would he had sacrificed himself for what the Greeks have become — not the proud descendants of Leonidas and Themistocles, but a race resembling beggars with palms outstretched to the bureaucrooks of the EU.

No people in history venerated their heroes more than us Greeks, and we sure had plenty of them to look up to. Add one more: the name of Kostas Perrikos, born in Chios in 1905, died a hero in 1943. Next time you are in Athens, look up his statue on the corner of Patission and Gladstone. And remove your hat while doing it.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in