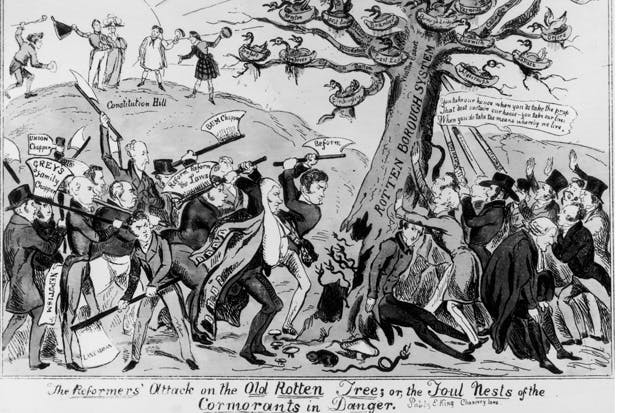

When The Spectator was founded 188 years ago, it became part of what would now be described as a populist insurgency. An out-of-touch Westminster elite, we said, was speaking a different language to the rest of London, let alone the rest of the country. Too many ‘of the bons mots vented in the House of Commons appear stale and flat by the time they have travelled as far as Wellington Street’. This would be remedied, we argued, by extending the franchise and granting the vote to the emerging middle class. Our Tory critics said any step towards democracy — a word which then caused a shudder — would start a descent into chaos. On the contrary, we said, the choice was between reform or a ‘revolution of the most sweeping character’.

After some struggle, the British political system’s sense of self-preservation kicked in and the Great Reform Act of 1832 was passed. That year was tumultuous, certainly, but less so than the revolutions that went on to sweep so much of unreformed Europe.

For all of its anachronisms, the British parliamentary system has proved itself to be the most responsive in the world. For almost two centuries, it has offered a lesson in how to handle what is too often called populism: if you respond to what is troubling people, the ‘populism’ tends to go away.

It might well be that 2016 will be remembered as a year when one decaying order finally collapsed and a new one took its place. New, of course, doesn’t necessarily mean better. What happens next in Britain remains an open question: Brexit is not (as some of its more naive cheerleaders suggest) a guarantee of a better future. It is merely the removal of a constraint. Whether we flourish or flounder will depend on how well, or badly, Theresa May and her successors handle the transition.

It will take a decade, possibly longer, before Brexit can be judged to be a success or a disaster. But the first signs are encouraging and populism, for now at least, is one problem Britain does not have.

On the continent, things are rather different. The state of Italian politics is tragic, and France is not much better. Serious questions are being asked about the merits of democracy; each coming national election seems to be viewed with trepidation in the chancelleries of Europe. The line in the Bertolt Brecht poem, ‘Would it not be easier … To dissolve the people/ And elect another?’, seems to sum up the attitude in various capitals. It’s easy to deplore leaders such as Marine Le Pen, Beppe Grillo and Donald Trump. But it’s harder to ask why so many support them, and whether those supporters might have legitimate grievances.

When intransigent politicians face a democratic challenge it is, overall, a healthy sign — even if it can be unedifying at times. Look beyond politics, and things are going rather well in the areas that matter most. Britain’s economic recovery may be slow, but household disposable income closes this year at a record high. As does the employment rate. Crime is at its lowest levels since surveys started in 1981 — a year when 61 per cent of Britons were living in what we would now call absolute poverty. Now the figure is 20 per cent: still too high, but lower than at any point in history.

Look up recent statistics for worldwide poverty, disease, hunger and ignorance and you see each of these giant evils in headlong retreat. Bill Gates speaks of being able to abolish poverty as we know it within our lifetime. He’s quite right. Since the Cold War ended, the global poverty rate has fallen by three quarters.

There is no doubt that the old rules of western politics are being rewritten, the clichés disproved and old electoral playbooks abandoned. But this is not in itself a reason to panic. There can be a tendency among politicians to confuse their own disorientation with the end of the world — when, in fact, the world is doing rather well. By most objective measures of human progress, this has been yet again the best year ever. It might go against our instincts and against much of the news agenda — but most of us have never had firmer grounds for expecting, or for wishing others, a happy new year.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in