When turbaned warriors from Daesh (or Isis) advanced on Raqqa in Syria two years ago, they whooped wildly about having ‘broken the Sykes-Picot Agreement’. They were celebrating athe destruction of national frontiers which had stood for nearly a century, since the fall of the Ottoman empire in 1918.

They were also venting their spleen against the two villains (as they saw it) of the piece — one British, Sir Mark Sykes, and the other French, François Georges-Picot, who, after months of diplomatic haggling, had drawn metaphorical lines in the desert sand to reach their secret 1916 agreement apportioning Ottoman lands and creating the modern Middle East.

In doing so, Sykes and Picot set aside promises of an Arab homeland made to Sharif Hussein of Mecca. Together with the Balfour Declaration, their pact not only perpetuated western influence in the region but advanced the cause of Zionism.

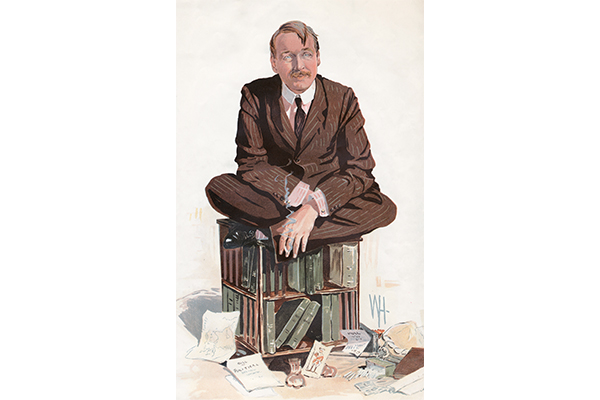

Christopher Simon Sykes, best known as a photographer of country houses, had long been curious about his reviled grandfather Mark who died, exhausted, in the Spanish flu epidemic of 1919. (I don’t know the author; Christian names are the easiest way of distinguishing the two men.)

By all accounts, Mark was remarkable, with his fierce curiosity, sense of humour and passion for the Arab world, which he vividly conveyed in hundreds of letters to his beloved wife Edith, many of them lavishly illustrated with line drawings or cartoons.

His father Tatton Sykes, the fifth baronet, was a neurotic who escaped the drudgery of running Sledmere, his large Yorkshire estate, by embarking on lengthy trips to the Middle East. Hearing of his own father’s death while in Egypt, his only comment was: ‘Oh, indeed. Oh, indeed.’

He often dragged along young Mark on his travels. The boy’s initial education had been among the books in the library at Sledmere, where the grounds fostered his love of military games and fortifications. At his father’s side in Ottoman lands, Mark became familiar from an early age with Arab hospitality and culture, as well as with musty British embassies.

Mark’s impulsive mother Jessie, née Cavendish-Bentinck, pulled in another direction, after finding consolation in Roman Catholicism. After a belated christening, where his godfather was the Duke of Norfolk, he attended Beaumont, the ‘Catholic Eton’, while Jessie looked to alternative panaceas — gambling, affairs and drink. When her husband absolved himself of responsibility for her debts, she resorted to money lenders, leading to a distressing court case in which ‘Lady Satin Tights’ (as she was derisively known) was found to have forged his name on promissory notes.

Jessie intended Mark to go to Trinity College, Cambridge. Arriving there late for an interview, she excused herself by saying she had been at the Cesarewitch. When the nervous Master replied, ‘Oh, and where may that be?’, she concluded he was a cretin, turned tail, and put her son down for Jesus.

Despite Mark’s own traumas (after he impregnated a servant girl, his father ordered his favourite dogs to be hanged), he continued his explorations of the Ottoman world. While an undergraduate he wrote his first book, Through Five Turkish Provinces (later trumped by Dar-ul-Islam: A Record of a Journey through Ten Asiatic Provinces of Turkey). A common theme was his scorn for Europeans’ dismissal of eastern customs.

During the Boer War, he excoriated dim-witted British officers and put his enthusiasm for ramparts to practical use. Wiling his time in the veldt, he also indulged his aptitude for drawing and storytelling, writing a spoof book about military training under the pseudonym Major General George D’Ordel, who featured in two further volumes on official ‘spin’ and the popular press, the last of which was described in a review as ‘probably some of the most brilliant nonsense ever written’.

After Cambridge, Mark followed a traditional career path for a young man of his caste as private secretary to George Wyndham, Chief Secretary to Ireland, and honorary attaché in the British embassy in Constantinople, where one intelligence-gathering expedition led to his Report on the Petroliferous Districts of the Vilayets of Baghdad, Mosul and Bitlis.

After becoming an MP, his fascination with Arab (really Ottoman) affairs propelled him through various committees about the future of the region to his negotiations with the fiercely nationalist Georges-Picot.

Turkey’s entry into the war on Germany’s side altered Mark’s inclination to preserve the integrity of the Ottoman empire. He began to support Arab aspirations for independence. But he realised a post-war accord in the Middle East required French involvement. As a Tory romantic who had admired Disraeli (and hated Gladstone, the scourge of Turkey’s ‘Bulgarian atrocities’), he succumbed to the attractions of Zionism and helped draw up the Balfour Declaration, which promised Jews a national home in Palestine.

Christopher tells this complex story with gusto, though he adds little to the existing literature. Judging from his bibliography, his material is dated: no mention of James Barr’s A Line in the Sand (2011), for example. A decent map would have been welcome. The reproduction of so many of Mark’s wispy cartoons, while evocative, seems a trifle haphazard, a first outing for a personal treasure trove.

But Christopher did not set out to write a history of the Middle East. (His editor once suggested an alternative title — ‘The Man Who Fucked Up the Middle East’.) He aims to put a human face on a imperialist adventurer, and in this he succeeds brilliantly. Mark’s fiercely independent spirit shines through. He meets all sorts of characters from Cecil Rhodes to Gertrude Bell, a potential rival whom he dismisses as a ‘silly chattering windbag of a conceited gushing flat-chested man-woman globetrotting rump-wagging blethering ass!’

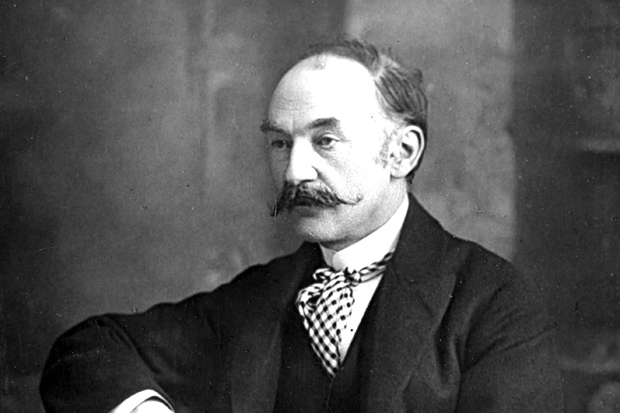

Looking back on Mark in Seven Pillars of Wisdom, T.E. Lawrence took a harsh line: ‘His instincts lay in parody: by choice he was a caricaturist rather than an artist, even in statesmanship.’ That’s a sad reflection on a man whose best known squiggle — that fateful line on the map ‘from the “e” in Acre to the last “k” in Kirkuk’ — did much to shape the modern world.

The post A fateful squiggle on the map appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in