Helen Gurley Brown’s internationally influential career, as the author of Sex and the Single Girl and editor of Cosmopolitan, is revealed in this intimate biography in 50 shades of pink. ‘Let it be understood at the outset,’ writes Gerri Hirshey, an American freelance journalist for many upmarket periodicals:

Sex has imbued the soft core, hard times and glory days of this story — sex surrendered, sex wielded, lavished and revelled in, sex merely endured and sometimes coolly transactional, sex reimagined, promised and packaged on glossy magazine covers for global dissemination…

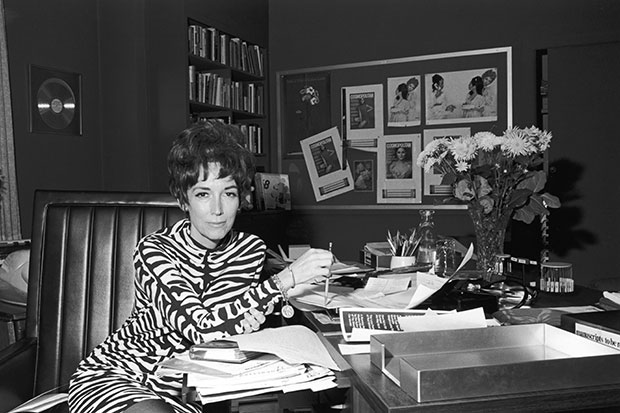

Hirshey tells all about Helen’s life, every nook and cranny, from her childhood poverty in hillbilly Arkansas, steeply ascendant to the pizzazz of A-list Manhattan. She is a connoisseur of pizzazz, and her style is suitably ornate.

Helen’s father Ira was a brutal misogynist, nicknamed ‘Caveman Gurley’. Her mother, Cleo, experienced agonising obstetrical difficulties giving birth to Helen and her older sister Mary, was later crippled by polio, and was depressed and pessimistic ever after. When Helen was only ten, Ira died while attempting to get into a lift already moving. Helen inherited financial anxiety and remained parsimonious even when she made lots of money. ‘By the time Mary and Helen were school age,’ Hirshey relates, ‘Cleo had begun her steady warnings that pretty girls got the best in life, and her daughters had better learn to use their brains and wits.’ Helen was made to believe she was not at all pretty, and in adolescence was further handicapped by chronic acne, hence the book’s title. As a young woman she lived according to the creed she would proclaim always: to have and to hold men, the single girl must exert inner charm above the neck and below the waist. Helen also persuaded generations of girls that there was nothing morally wrong about heterosexual intercourse before marriage. She campaigned for women’s rights in the bedroom and the boardroom, for the contraceptive pill and, in the event of carelessness, for abortion.

In a series of secretarial jobs and as a smart advertising copywriter, Helen found that the single life, if sufficiently promiscuous, could be satisfying more often than not. She later recalled that she ‘made love’ with 178 men before, at the age of 37, she decided to settle down. The years of research and rehearsal enabled her eventually to find a perfectly compatible Mr Right.

In 1959, she married David Brown, a divorcé six years her senior, the producer who conceived Cleopatra, perhaps the most spectacular commercial flop in the history of cinema, and then several great hits, including Jaws and The Sting, which made him rich for the rest of his life. He increased the couple’s prosperity by shrewdly guiding the composition and marketing of Sex and the Single Girl, based on the irrefutable theory that literary works sell best with the highest possible erotic content. ‘This is not a study on how to get married,’ she wrote, ‘but how to stay single — in superlative style.’ She offered young womanhood ‘lubricious operating instructions’. The book sold like diaphragms, more than two million copies in the United States, was a bestseller in 28 foreign editions, in 14 languages, and is still in print almost everywhere.

There was a certain inevitability that such a talent should be recruited to save Hearst’s Cosmopolitan from ignominious failure. Under Helen’s editorship, with her husband whispering salacious suggestions in her ear, Cosmo, as the magazine was affectionately known in 35 languages, in 100 countries by 68 million readers, became, Hirshey notes, ‘the largest young women’s magazine in the world’. Its dominance was maintained by Helen’s fearless pioneer spirit, constantly devising new ways of promulgating the most important Lessons in Love of her popular LP record: ‘Capturing a Man if You Aren’t Pretty’ and ‘How to Talk to a Man in Bed’.

It was Helen who exhibited the word penis in Cosmo for the first time, in November, 1970. It was Helen who presented Cosmo’s first nude male centrefold, in April, 1972, with a portrait of Burt Reynolds, naked on a bearskin rug. That issue sold 1.55 million copies. From 1965 to 1972, Helen doubled the magazine’s circulation and advertising revenue.

While making publishing history, Helen did all she could to improve her appearance with cosmetic surgery, for David’s sake. When she died, in 2012, only two years after him, a line in the opening paragraph of her New York Times obituary was accurate but rather bitchy: ‘She was 90, though parts of her were considerably younger.’ If only Helen and David had been able to read that, wherever they were, how they would have laughed.

The post Lessons in sex appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in