It’s a little know fact that when French aristo Baron Pierre de Coubertin averred that ‘the important thing is not to win but to take part,’ people thought he was talking about la guerre, and trying to post-rationalise France’s dismal performance in every cross-border conflict since the Norman Conquest. When they realised he was talking about sport, and specifically the multinational quadrennial sporting jamboree he’d just founded, even his compatriots began to suspect he’d been at the absinthe. After all, nobody in their right mind would claim that elite level sport has ever been about anything but winning, and especially so when national pride is at stake. The good baron may have dreamed of a level playing field where individuals set aside ethnic and cultural differences to compete in a spirit of friendship. But two world wars and countless Western interventions later the reality is that for some of its most enthusiastic participants the Olympic Games will always be theatres of geo-political conflict and other countries’ athletes will always be enemies, not rivals. And while the suffering which results may be limited to popped shoulders and pulled hammies everyone sees the subtext: Impressed by that javelin throw? You should see how far our ICBM’s can go. Think our swimmers are synchronised? – take a look at our infantry parades. OK, we’re not much good at fencing – but you should see the wall we’re gonna build!

And these days It’s not enough for us to see our Olympians give it their best shot. What was acceptable to the viewing public twenty years ago falls well short of expectations in the era of reality TV and ‘closure’. The era when sponsorship and media contracts require athletes to have microphones and cameras shoved in their faces immediately after competing, too – preferably while they’re still coming to terms with their performance, however bad it was. Athletes who failed ‘to medal’ used to be allowed to process that failure in the seclusion of a team bus or hotel room. Now, because of the modern media consumer’s appetite for emotional pornography, that misery has value. So now the networks must show – in high definition – the quivering lip, the faltering voice and the welling tear as a teenager who has shouldered the hopes of millions for the past year realises (thanks to prompts from the interviewer) just how much he or she has let everyone back home down and how awful the rest of his or her life will be in consequence. From a ratings and social media perspective Cate Campbell’s failure to win a medal in the final of the 100m freestyle was less disappointing than her failure to burst into tears when she climbed out of the pool and her cheerful dignity at the post-race debrief.

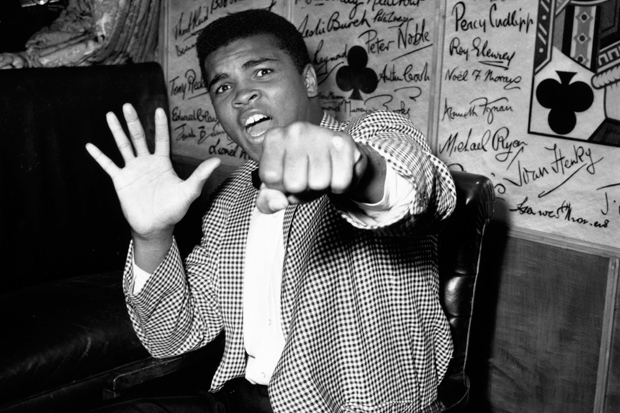

And if there’s anything that modern audiences hate their sporting heroes to display more than stoicism it’s modesty. Remember the gob-smacked ‘Did that really happen?’ expression on the face of Adelaide wunderkind Kyle ‘big tuna’ Chalmers when he realised he’d won the 100m freestyle final? He was still in such stunned mullet mode when channel 7 got to him that he could only mumble a few self-effacing comments about the quality of the rest of the field and what an honour it was to have been in the same water. Bo-ring. Compare that to any of the 500 Usain Bolt interviews you can find on Youtube. I say any because he covers pretty much the same ground in all of them; that he is the best at what he does and that nobody in the world has a chance of beating him. The well of Bolt’s self-confidence is so deep that he doesn’t even wait for victory to enjoy its spoils. ‘People will say I’m, like, a legend, like Pele and Ali,’ he mused about his Rio trifecta – the day before he achieved it. There was a time when boasting about your abilities, especially on the sports field, would not have endeared you to the general public. In Australia we took particular exception to sportsmen and women who had tickets on themselves. But somewhere along the line the world changed its mind about skiting. Do you remember when it was that boasting became acceptable? And do you remember who made it so? The man who killed sporting modesty died himself less than a year ago. And do you remember when he did it? When he first declared himself to be ‘the greatest’? After winning a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics, of course. The Baron must be spinning in his grave.

The post Simon Collins appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in