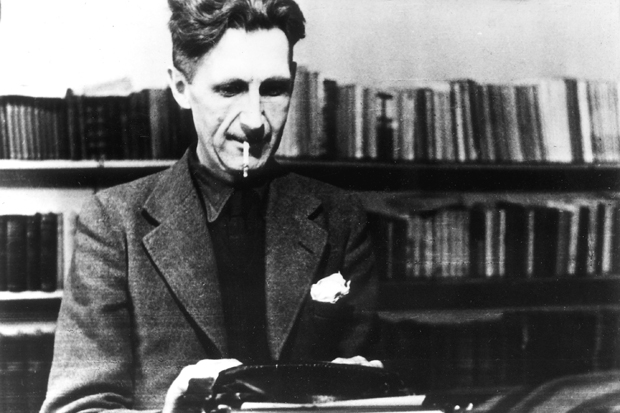

The Orwellian past is a foreign country; smells are different there. Pipe smoke and carbolic, side notes of horse dung and camphor — and that most inescapable odour, the ‘melancholy smell of boiled cabbage and dishwater’ seeping under a parishioner’s front door in A Clergyman’s Daughter. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, too, the hallway of Victory Mansions ‘smelt of boiled cabbage’. That was the quotidian stench of my childhood; long gone now, both the cabbage and the childhood.

When Professor John Sutherland began re-reading Orwell after losing his sense of smell three years ago, the old familiar writings seemed ‘interestingly different’, their olfactory obsessions suddenly more conspicuous. He isn’t the only critic to notice how whiffy Orwell’s work is, but certainly the first to muse about it at such length. ‘Orwell was born with a singularly diagnostic sense of smell,’ he writes. ‘He had the beagle’s rare ability to particularise and separate out the ingredients that go into any aroma.’

Constructing a ‘smell narrative’ for A Clergyman’s Daughter, Sutherland retells the story purely through its aromas. Dorothy comes downstairs to the chill morning smell of dust, damp plaster and the fried dabs from yesterday’s supper, goes to church (‘a scent of candle-wax and ancient dust’) and encounters the lone midweek communicant, Miss Mayfill, with her ‘ethereal scent, analysable as eau-de-cologne, mothballs and a sub-flavour of gin’. And we’re still in chapter one.

As a lifelong chain-smoker it’s remarkable that Orwell had any sense of smell at all, let alone such an acute one. But why was he so often led by the nose? Here Sutherland swaps his professorial chair for a psychiatrist’s couch, none too comfortably: ‘One suspects Blair/Orwell was of that sexual group of paraphiliacs for whom Freud could only devise a French term — renifleurisme; male erotic gratification from the covert sniff.’

Whence this suspicion? Guilt by association, partly: Orwell read James Joyce, who was a connoisseur of sexual smell. But here’s the clincher: Orwell was a keen angler. ‘The smell of fish is notoriously erotic for the renifleur-inclined, and there is a vague sexual gratification that one doesn’t like to dwell on too much.’ Coarse fishing, eh?

Some of Sutherland’s speculations sound more like trolling. ‘Joyce, an unashamed coprophiliac (as one can conjecture, was Orwell — hence his recurrent use of the word ‘faecal’)….’ Which prompts another conjecture: ‘Was he… a coprophage?’ And another: ‘Orwell was a flagellophile. He derived, that is, a fetishised sexual thrill from the whip and being whipped.’ After all that, one supposition seems almost otiose: ‘Orwell surely masturbated.’

Inside Orwell’s Nose a slim volume called ‘Orwell’s Dick’ is wildly signalling to be let out. Sutherland is more illuminating when his critical attention returns to the schnozzle, sniffing out every odour in the art and the life — tracing, for instance, a line of descent from an Orwell comment about his tramping days (‘I shall never forget the reek of dirty feet’) to Gordon Comstock’s adverts for foot deodorant in Keep the Aspidistra Flying.

The pongs and perfumes of Orwell’s work establish a mood as effectively as music in a film. After an exhaustive process of ‘naso-criticism’, Sutherland finds Coming Up For Air to be ‘the most aromatic of Orwell’s novels. There are passages that fairly caress the nostrils.’ Down and Out in Paris and London, by contrast, is so mephitic that ‘you could, you feel, contract bronchitis or worse from the miasma rising from the pages’.

In The Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell famously evoked middle-class attitudes in ‘four frightful words which people nowadays are chary of uttering, but which were bandied about quite freely in my childhood. The words were: The lower classes smell.’ But then who didn’t? William Empson, who occupied a neighbouring cubicle at the BBC during the war, said the only stink worse than Orwell’s black-shag tobacco was his suffocating BO. Sutherland makes much of this, but surprisingly omits to add that the author of The Structure of Complex Words was no less niffy than the creator of Newspeak: according to Empson’s biographer, ‘his unhygienic habits were the subject of remark’ at the University of Sheffield, where he once told a colleague: ‘I don’t think one needs a bath in winter, do you?’

Orwell often lived in places with no washing facilities, and in the company of chickens and goats. He loved farmyard smells: cows grazing in a meadow were scented ‘like a distillation of vanilla and fresh hay’. Sutherland thinks it significant that there are no animals in Nineteen Eighty-Four — apart from the rats, of which the author’s phobia was as intense as Winston Smith’s.

Orwell’s nightmare is a world from which wholesome smells have vanished, leaving only ‘the stenches of totalitarian oppression’: sweat, shit, rot-gut Victory Gin, tinny coffee — and boiled cabbage.

The post Gin and boiled cabbage with George Orwell appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in