Helen Rappaport’s new book makes no claim to be a complete account of the Russian revolution. Instead it presents a highly readable and fluent description of the events of 1917 in the capital, Petrograd, as experienced by the city’s many foreign residents. Russia’s booming prewar economy had attracted every sort of business person and technical expert, as well as diplomats, journalists, adventurers and fleets of governesses. Their first-hand revolutionary experiences were too extraordinary not to record, and those who did not write contemporaneous accounts often produced memoirs later. Rappaport has unearthed striking new material from archives in Russia, the US, France and at the University of Leeds.

From the start of the year everyone from ambassadors to actresses seems to have been struck by the atmosphere in the city, ‘taut as a wire’. There were serious food shortages and people queued through the night for bread. Thousands of laid-off workers milled around the streets, while strikes and riots were put down viciously by Cossacks and the hated ‘Pharoahs’, mounted police armed with sabres. Meanwhile the opera was still crammed, and at the New Year’s Eve parties, Moët et Chandon Brut Imperial flowed in streams. When revolution finally broke out at the end of February, only the Tsar was taken by surprise, it seems; behind the front lines in Mogilev, he had ignored warnings from many in the foreign community.

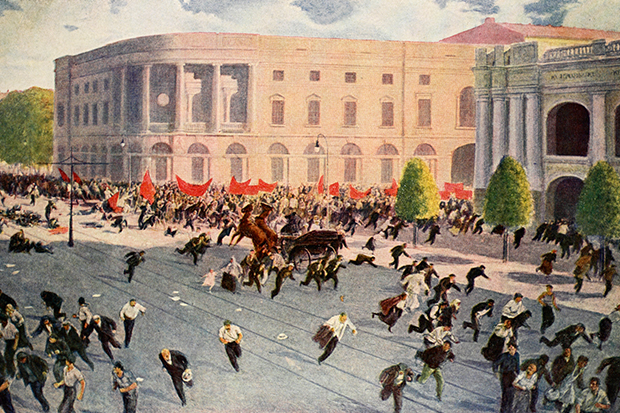

Histories have usually portrayed ‘the February days’ — the mass demonstrations and riots that cumulated in the Tsar’s abdication on 2 March — as a more or less peaceful revolution, an exhilarating moment of unity between Russians of all classes. Many of Rappaport’s witnesses did report on the air of celebration, the good humour of the crowds and the swiftness with which normal life returned. Others, for example the intrepid American journalist Florence Harper and her photographer Donald Thompson, who spent several days on Nevsky Prospect, had a different experience. They saw at close hand many casualties in the crowds, as well as victims of mob violence — above all the ‘Pharoahs’, who were hunted down, thrown off roofs, lynched and beaten to death. The official figure was 1,382 killed and wounded, yet diplomats and journalists at the time calculated the dead to number somewhere around 4,000 to 5,000, with some estimates as high as 10,000. In any case, ‘agreeable statements made as to the bloodlessness are much exaggerated’, as James Pollock, a British eyewitness, remarked.

Whether flavoured by the hindsight of memoirists or not, the period of provisional government (from the Tsar’s abdication to the Bolshevik coup in late October) comes across in these pages as an inevitable progression towards the next revolution. Soldiers at the front were abolishing ranks, beating up their officers and deserting, while life in Petrograd consisted of strike after strike, endemic robbery and street violence. British, French and American diplomats had one overriding concern —that Russia should remain in the war. Their stubborn insistence on this point, so clearly against the interests of their friends in the provisional government and the Russian people, suggests that the Allies played their own small role in bringing the Bolsheviks to power (their ineffectual military interventions during the civil war also contributed).

The coup, when it came, was no ‘heroic workers’ showdown’, Rappaport writes, but more an ‘exhausted capitulation of Kerensky’s moribund and virtually defenceless government’. On the night of 24 October, the Bolsheviks seized key points in the city and fired on the Winter Palace from the battleship Aurora. The palace, defended only by cadets, a bicycle squad and 135 members of the Petrograd Women’s Battalion, surrendered more or less instantly, despite the fact that the Aurora was firing blanks. The Bolsheviks’ taste for blood was not long in awakening, however; an uprising of cadets (children of 15 and 16) was put down brutally a couple of days later.

At the end of her book Rappaport wonders about the hundreds of other members of the Anglo-Russian community that do not figure in it. I was moved recently to come across one of them in Lena Mukhina’s diary of the siege of Leningrad — an elderly, unpaid housekeeper named Aka, once a governess and possibly an English-woman. She shared the fate of so many in her adoptive country and starved to death in the terrible winter of 1941.

The post Exit the Tsar appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in