Oh, the longueurs of aristocratic Georgian leisure. What on earth did they do all day, with no domestic chores, no Wi-Fi, no television, no telephones for chatting and the slowest of transports to move their lives from the sticks to the bright lights of London or Bath? Kate Felus has written a fascinating book which tells us how the 18th-century landed gentry whiled away their summers out of doors. On winter she does not dwell, because, as she says, summer was the time when all the great landowners were likely to be at their country estates.

Apart from Margaret Willes’s excellent Gardens of the British Working Class, the documented social history of gardens tends to concentrate on grand, rather than humble, establishments. As late as 1820, we learn that the nobility consisted of just 350 families out of a population of 18 million, so the activities recorded in The Secret Life of Georgian Gardens are admittedly exclusive. The book’s research draws on writing and painting of the period, although Felus does admit that ‘it is likely that more everyday goings-on were not the subject of artists. There was nothing out of the ordinary in a lady writing letters in her ornamental cottage, or a gentleman practising his flute in his summer house.’ Occasionally, the author alludes to ‘the genteel and middling sort’ — the clergymen, doctors and farmers who enjoyed a scaled-down version of the pleasures of the upper class — but these references are infrequent.

Jane Austen’s novels are often quoted, and these are central to the period dealt with in the book. In Sense and Sensibility, the morning at Whitwell Park was spent sailing on ‘a noble piece of water’. Most large gardens had lakes, and boating was often a diversion, where sometimes mock battles were fought. These, the author suggests, were patriotic gestures and celebrations of British naval supremacy, as well, perhaps, as a training ground for younger sons destined for naval careers. But boating excursions could end in disaster. At Grimsthorpe Castle the 22-year-old composer Thomas Linley, often known as the English Mozart, was drowned when a summer storm capsized his boat.

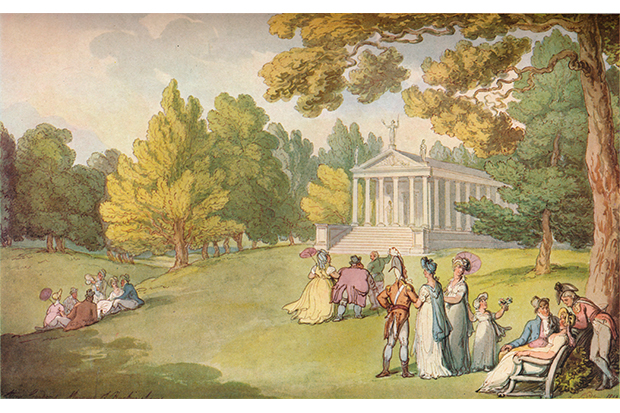

For a perfect summer day, like the one Jane Austen describes at Whitwell Park, cold provisions would be provided, which might be eaten at a summerhouse or temple, where they had been taken by servants in a wheelbarrow. As very few banqueting houses boasted kitchens, many journeys must have been made to carry all the china and plate needed, as well as the barrrowloads of food and drink.

Other estate staff might be deployed in the bushes to play musical instruments. But not perhaps near the privies, which were also hidden in shrubberies for the convenience of those enjoying the party. In the afternoon some people slept, or read or drew. The more active among them might garden. Lady Mary Coke wrote to her sister: ‘I am grown a great weeder. I am glad I like it better than my gardener. My garden would otherwise be in great disorder.’ But who, I wonder, cleared the weeds away? Even today, gardening ladies of the grander sort leave dead-headed roses on paths for their gardeners to remove.

Haymaking was also popular and a good way to keep children busy. Fishing, archery — very good for showing off the female form — croquet, bowls, cricket, quoits, battledore and shuttlecock were all occupations for killing time at country-house afternoons. Walpole admitted to his friend George Montagu that he feared boredom while staying for five days at Stowe, although for him this was not relieved by sport, but by the wealth and variety of garden buildings and the acting out of ‘a small Vauxhall’ at the Grotto.

The evenings were reserved for more lavish entertainments. Moonlit nights were especially chosen for the most important occasions, but lanterns (more work for the servants) must have made places far prettier than modern garden lighting can ever achieve. Dinner would be served any time between three and seven, and mostly took place in the pleasure grounds, rather than in the main house. Buildings, tents and rugs spread out on the ground were all possible settings, especially for dessert, which would be fresh fruit from the garden.

The standard ingredients of an evening’s entertainment, according to Felus, were ‘dinner, tea, syllabub, music and dancing’. At Parson Gilbert White’s modest four-acre place, they sang and dressed as shepherds and shepherdesses, as well as enjoying the extra diversion of the parson’s brother disguised as a hermit. Even modest meals outside needed elaborate execution by hidden hands. Why all of this Marie-Antoinette behaviour never resulted in a revolution is hard to fathom. But like the celebrity doings of our own day, these accounts of 18th-century douceur de vivre make for compulsive reading.

The post Playing at shepherdesses appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in