It’s not unreasonable to expect that the anatomy syllabus for a medical degree should include breasts.

Last year I performed full-body dissection as part of my training to become a doctor. After timid first incisions to the arm, we students were entrusted with opening the chest cavity. Two obstacles blocked the way. I looked in the course manual for directions about how to cut — through? around? underneath? But there was no mention of these pleasure-giving, milk-yielding, cancer-visited organs.

One justification for the vast expense of cadaveric dissection is to develop a clinical understanding of the body in its supposed entirety. Omitting the breasts reflects a way of thinking — from which medicine has not yet matured — that still sees the female form as a detour from the human standard.

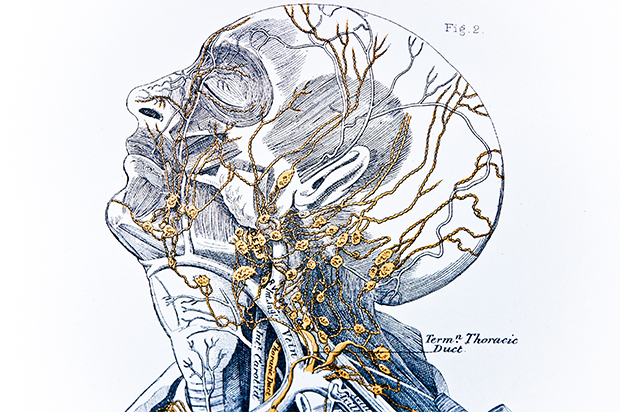

In This Mortal Coil, Fay Bound Alberti argues that the study of ‘anatomy is not merely a biomedical discipline, but also a philosophical endeavour’, to which I would add that it is also crucially political. The book’s central message is that mankind’s bony scaffolding, biochemical reactivity and nervous wirings have barely changed over millennia, but appreciation of how bodies work, whose bodies matter and the interplay between physiology and feeling has changed beyond recognition. We may look similar enough to Hamlet, but we don’t experience the world like him.

Each chapter focuses on a body part — the breast, the tongue, the spine — and traces a history of attitudes and oversights through the centuries. Alberti’s analysis at times leaves the people of the past feeling ‘remote from us because we know so much more than they did’, as T.S. Eliot said about his literary predecessors. Sperm and skeletal bone were once thought to be made of the same material; skin was considered a waste product excreted by the body; eating soap was believed to dissolve body fat. But, Eliot goes on, the people of the past ‘are that which we know’. It is humbling to remember that today’s medical textbooks are trusted temporarily, only to be scrutinised and corrected by posterity.

Alberti views secularisation as the force which led to the revision of our organ hierarchy. Until circulation was discovered by William Harvey in the 17th century, the heart was seen as the seat of the soul, where the material and immaterial met. Today, if you ask someone to point to where they feel love they might put their hand on their heart, but if asked where the ‘self’ resides, the brain usually wins. The head’s accepted supremacy relies on our understanding of electricity and computer logic, which rebranded the brain as a ‘motherboard’. This is not the end of the story: as knowledge grows about the intestine’s microbiome, with its 100 trillion-strong army of bacteria, scientists have upgraded its previous lowly status to a ‘second brain’. In her enthusiasm, Alberti blurs the profound differences between cerebral knowledge and the instincts of the digestive tract; we cannot trust our gut to solve a crossword, or cast a vote.

How we describe our body is important because words, particularly in the form of metaphor, come loaded with moral weight. Emotions can ‘boil over’; many of us will fight a ‘war against cancer’; women worry about the ticking ‘biological clock’, all of which contribute to a language of health and disease that powerfully influences behaviour. Despite Alberti’s sensitivity to figurative language, not even she is sufficiently careful when describing breasts as ‘stamped passports of women’s interactions with the world’.

This Mortal Coil hopes for a gender-sensitive medicine to ‘reinvigorate the body with the principles of holism that underpinned humoralism’. Alberti is critical of how patients’ bodies are currently divvied up between cardiologists, gynaecologists and dermatologists, while emotions are left at the hospital entrance. She overstates this fragmentation in her nostalgia for a medicine of the past. Many clinicians feel the humanist ideals of their vocation. The neurosurgeon Henry Marsh describes in his memoir, Do No Harm, how in the operating theatre his thoughts often turn to the significance of his scalpel’s path ‘through thought itself, through emotion and reason… memories, dreams and reflections’. Doctors must be encouraged to develop the mental agility to move between a mechanical and metaphysical view of the body. This process begins in the dissection room.

Even in anatomy, the most complete of the medical disciplines, things change. Two friends and I spoke up for the missing breasts. As of this year, the complete female body will be examined under the dissection room’s white lights. Future students will be delighted that there are yet more facts for them to learn.

The post Stiffen the sinews appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in