Initially it must have been a nasty surprise. On 16 August 1972 an amateur scuba diver named Stefano Mariottini was fishing in shallow waters just off the coast of Calabria. At about noon he was poking around some rocks when he saw part of an arm protruding from the sand. His first thought, a natural one, was that he had found a cadaver.

On closer examination, it became clear that there was not just one body but two — and that they were made not of flesh but of metal. Mariottini’s discoveries are world-famous now, taking their name — the Riace bronzes — from the little resort near which he was swimming. In terms of classical sculpture, he had hit the jackpot.

Bronze was the medium of choice for many of the most admired artists of the ancient world. But because it is also a useful material, which is easily melted and recycled, classical bronzes have — with extraordinarily rare exceptions — totally vanished. Furthermore, the works Mariottini had chanced upon were of self-evidently high quality and by and large in excellent condition. They seem to hold out a tantalising promise: a glimpse of what ancient Greek art at the highest level was truly like.

Not surprisingly — given that the only evidence is what can be deduced from the statues themselves and the place where they were found — there have been innumerable suggestions as to which sculptor (or sculptors) might have made them. They have been connected with many famous names, including Phidias, Polykleitos, Alkamenes and Myron (one difficulty being that no bronze by any of these survives for comparison). There has been a similar multiplicity of proposals for the characters from history or myth that they might represent.

Consequently, the bronzes have been dubbed just ‘Warrior A’ and ‘Warrior B’. There are differences between them —Warrior B seems older, more weary and more sympathetic — but both, though almost completely naked, were evidently armed and dangerous. Each originally carried a spear and shield; B once wore a helmet, long ago detached and disappeared.

Although inevitably there is disagreement about their exact dating, the bronzes may well come from the most admired period of all the epochs in Greek art. Many specialists place them in the mid 5th century BC, a little before the Parthenon sculptures were carved.

A classical archaeologist friend once suggested to me that these were the greatest sculptures of the male nude in existence, Michelangelo, Rodin and Bernini notwithstanding. Ever since he said those words I have wanted to see them and recently made the lengthy pilgrimage to do so on a slow Italian train.

For 35 years the bronzes have not left the regional capital closest to the place where they were found: Reggio di Calabria, which is right on the toe of Italy facing Sicily across the Strait of Messina. These are classical lands, but also turbulent ones. Reggio was settled by colonists from Greece in the 8th century BC, but little is now standing that predates the Edwardian era. Despite its rich history, the Italian deep south is short on monuments because just about everything — Greek temples, Byzantine churches, Norman castles — has been destroyed in war or fallen down in the constant earthquakes that plague this seismically active area.

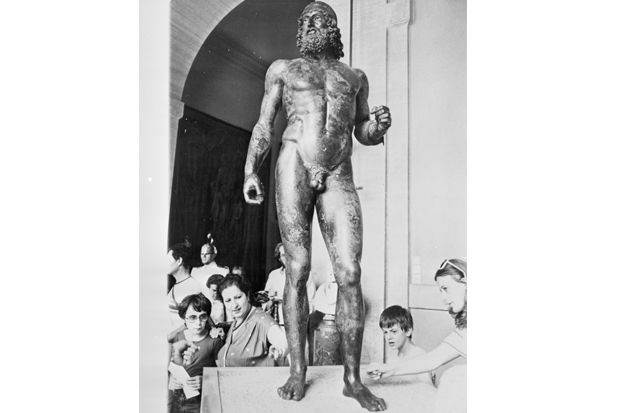

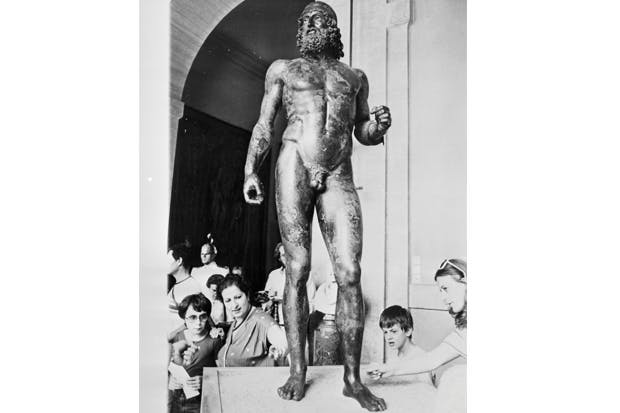

The bronzes are displayed at the Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia, devoted to the ancient cities of southern Italy, which reopened a year and a half ago after a lengthy and expensive refurbishment. Before you actually see them you have to spend some time in an airlock, from which you emerge to stand at close quarters to Warrior A, the younger, better preserved and more alarming of the two standing on his special earthquake-resistant plinth.

Although idealised and therefore anatomically inaccurate, the figures are compellingly real in presence — much more so than the battered surfaces of marbles of similar date. One of the qualities that gave bronze its appeal is that in colour it is close to sunburnt skin; the Riace figures were further embellished with copper lips and nipples. A couple of years ago, to the museum authorities’ consternation, a photographer surreptitiously shot one wearing a leopard-skin thong and pink feather boa.

This indignity, however, was not just a bad joke but contrary to the disquieting spirit of the bronzes. They are extraordinary examples of the rational ordering and redesign of the human body that was one of the great achievements of 5th-century Athens. But the effect is very far from the ‘noble simplicity and calm grandeur’ that the 18th-century art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann famously considered the defining qualities of Greek art. The British sculptor Elisabeth Frink, who was fascinated by the bronzes, got it right. They are, she noted, ‘very beautiful, but also very sinister’.

My instinctive reaction was alarm. Warrior A’s eyes, of white stone, give you a hard look; he opens his mouth revealing a set of sharp silver teeth. He looks like a killer, which is of course — whatever god or hero he represents — exactly what he was. Much more than calm or nobility, he has the quality, which interested Frink, of thuggishness. The two sculptures are an extraordinary intellectual and artistic accomplishment, but they visibly came from a violent and terrible world — which is what the Mediterranean has so often been.

The post Heavenly bodies appeared first on The Spectator.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in