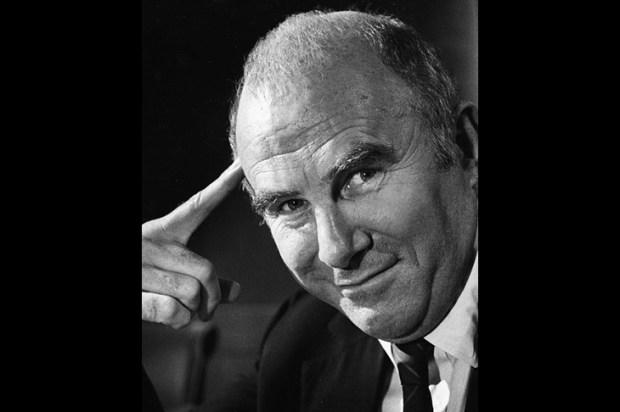

Richard Dorment doesn’t do whimsy. Or Stanley Spencer. He’s a fan of Cy Twombly and Brice Marden, Gilbert and George and Mark Wallinger, Rachel Whiteread and Susan Hiller. He loves writing about contemporary art. And he worked as art critic of the Daily Telegraph for 25 years. Like the grit in the oyster he irritated the establishment, producing pearl after pearl that occasionally had even his own paper distancing itself from his opinions.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £21.00. Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in