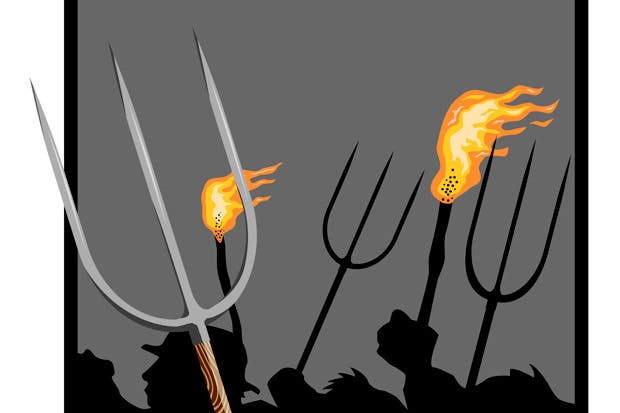

In a way the headline to my fellow columnist Dominic Lawson’s Sunday Times commentary on 12 April said it all. ‘Join the pitchfork wavers on tax, Mr Cameron, and you end up skewered.’ The column had something of an 18th-century ring to it, conjuring in my mind’s eye an elegant London dinner party, with men-about-town in powdered wigs twitching back the heavy damask curtains to sneak worried glances at a riot outside: an unruly and enraged mob rampaging up the street.

But Dominic had a powerful argument. It was, he suggested, noblemen like David Cameron and George Osborne who had unwittingly energised the rabble. Dominic had warned his readers of this four years ago, when the Prime Minister and Chancellor had trumpeted their moral repugnance at the comedian Jimmy Carr’s use of a legally approved scheme to minimise tax. I don’t myself think there is moral equivalence between Mr Carr’s elaborate arrangements and Mr Cameron’s father’s use of a common and straightforward investment vehicle, but Dominic’s point was that if you encourage people to ask not only ‘Is it legal?’ but ‘Is it moral?’, you’re on a slippery slope.

And so you are. So we all are this week; slithering around in ambiguous territory with few footholds. We’re all pretty clear that choosing e-cigarettes in place of tobacco for our nicotine hit is tax avoidance of an unimpeachable kind, while investment vehicles that hide the real beneficiary’s identity are morally dubious. But in the territory between those two, we struggle to draw the boundary — and always will.

I wish, however, to issue a hesitant peep on behalf of the pitchfork brigade. Should we be unwaveringly hostile to the British public’s ‘periodic fits of morality’ that Macaulay so memorably mocked? Fits of popular morality have helped spur on reforms in our history that we hardly regret. Public opinion was used to good effect in the campaign against slavery; and again by Dr David Living-stone in his campaign against slave trading in British possessions toward the end of the 19th century. The treatment of women in prisons, the use of child labour, successive reforms of our electoral franchise… in every case reform came in part as a result of public anger whipped up against practices that were perfectly legal but increasingly felt to be immoral — the distinction that Mr Lawson seems to deplore in the case of taxation.

Politicians need kicking on sometimes. Charles Dickens’s grasp of law and politics was crude, but he understood this truth. Fierce competition between rival politicians for public approval may be unedifying to watch, may be cynically calculated, and may risk the operation of the law of unintended consequences, but isn’t that what democracy is supposed to do: make those who govern us respond to our beliefs, our opinions and our feelings? Some media commentary on the right this week has seemed to hint that this would be a bad thing.

And sometimes it might. Especially this is true when a great wave of public indignation temporarily swamps reason. Such frenzies can be as evanescent as they seem at the time to be unstoppable; and the modern news cycle in tandem with the social media has increased the speed and ferocity with which they can arise — and subside. Some of the opinions now sloshing around on tax do seem to be of this frenzied and silly kind, and commentators like Lawson are right to warn of the dangers.

But pause to remind yourself why it is that this national anger about tax avoidance has proved so easy to fuel. We’re not talking here about a sudden or capricious opinion that has only recently and probably temporarily tipped the public mood. The feeling is long-standing and deep-seated that there’s something very unfair about the rich being able to afford schemes that greatly reduce the tax they pay, while middle- and low-income people have to pay their full whack. Is this moral sentiment wrong? I think not. People genuinely don’t mind pulling their weight if they’re confident that other people are too. The thought that one is oneself paying dues that citizens much richer than oneself are managing to duck enrages people, enrages me, and should. If, as Dominic suspects, people like Cameron are ‘pandering’ to that, then I say, ‘Pander on. You should.’

Much of my family live in Spain. There has arisen there the widespread view that everyone with power, titles, money or connections is on the take in some way. This gives rise to an enervating national cynicism in which until recently people hardly bothered to protest or try to change the system, but instead resigned themselves to cheating too, just like everyone else. In Britain we have yet to come to that. Not only do people not accept that ducking your taxes is right — they believe that we, the people, are in the position to combat these practices. Rage is not impotent but constructive, directed. Is that unhealthy?

Cynics and impossiblists point out that as long as tax havens exist, people will use them. Pressed harder, they would advise (as Lawson does) that we stop blaming those who take advantage of loopholes and instead work to close them. But why has it proved so hard to close them? Many believe (I do) that too many world leaders and their friends have a direct or indirect interest in the existence of jurisdictions like Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Panama or the Cayman Islands for it to be easy to get the international consensus required.

In which case, maybe we need the tumbrils? Maybe we need the enraged mob. Maybe we need large bodies of fairly ignorant voters, hazy about the details and often wrong in the targets they choose, but united by the feeling that it isn’t fair that money can buy you exemption from the tax liabilities that poorer citizens are unable to avoid?

There is a place for pitchforks in democratic politics. Dominic thinks that by egging their bearers on, our leaders may be skewered. Perhaps. But turning away in fastidious distaste can get you skewered too.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in