‘This happens to other people.’ The Guardian journalist Decca Aitkenhead says she had heard the phrase countless times, interviewing the survivors of random disasters, and the idea had always puzzled her: ‘Why would they think other people are any different from them?’ But when her partner of ten years drowned while rescuing their small son from the Jamaican sea on a family holiday in May 2014, she was startled to catch herself feeling exactly the same thing.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

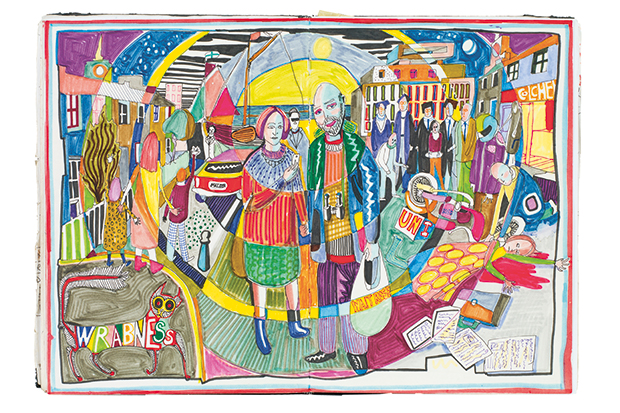

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.99 Tel: 08430 600033

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in