The other day, some anti-imperialist students were questioning the presence in their institutions of statues of Cecil Rhodes, a West African cockerel and, very strangely in view of her conspicuously anti-racist convictions, Queen Victoria. In response, a Guardian columnist, who has probably made less effort to learn Hindi than Queen Victoria did, amusingly said that it was time to ‘start a debate’ about the British empire.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

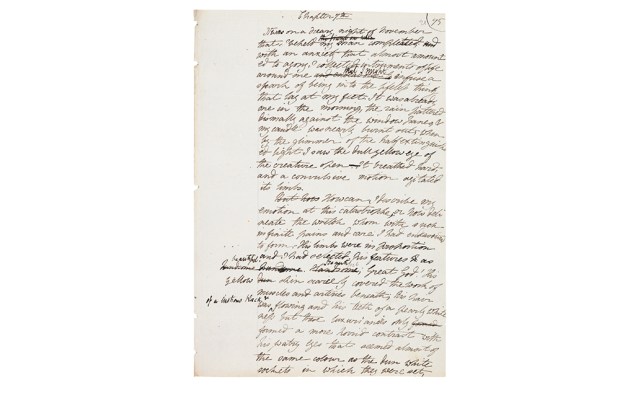

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £25.00. Tel: 08430 600033. Philip Hensher’s novels include The Mulberry Empire, about Afghanistan in the 1830s.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in