Listen

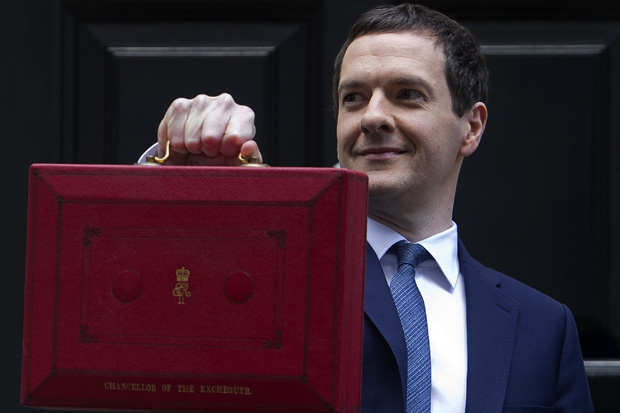

George Osborne used to tell his aides to prepare every budget as if it were their last: to throw in all of their best and boldest ideas. But this week, the Chancellor has opted for political as well as fiscal retrenchment. This was a cautious budget. Its emphasis on infrastructure was as laudable as it was uncontroversial. There were few hostages to parliamentary fortune, which is sensible given the Tories’ small majority and the way in which the EU referendum is challenging party discipline.

British government is on hold. Ever since Cameron struck his EU deal he has done little else but make the case for it. Even pro-EU ministers complain how difficult it has been to claim a spot on the government grid for anything unrelated to the referendum. Loyalist Tory MPs have urged No. 10 to put some other issues on the agenda and give the party something — anything — else to talk about. This problem has been compounded by the PM’s many trips to Brussels to deal with fallout from the migration crisis.

That Cameron’s domestic agenda has been superseded is particularly depressing, as he had been hitting his stride. His one-nation social agenda had given him a defining purpose as Prime Minister and was moving the Tories into new and electorally fertile intellectual territory. At its best, Tory modernisation is about achieving progressive ends by conservative means, and he had begun to do that on a host of issues, from addiction to prisoner rehabilitation.

Osborne’s Budget sought to bring some of these themes back to centre-stage. The government’s plan to make every school an academy is a sign that the domestic reform agenda continues. Cleverly, it also reminds Conservative MPs that they are on the same side against the vested interests of the educational establishment.

To some in government, the way the referendum is draining energy from the domestic reform agenda is a reason to vote ‘in’. At the Saturday cabinet meeting that discussed the EU renegotiation, Environment Secretary Liz Truss argued that if Britain left the EU this would take up all the government’s time and nothing else would get done. Her point was that the Tories would miss a golden opportunity to get on with their domestic reform agenda. They cannot be certain that the opposition will remain as weak and as divided as Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, which only added potency to her argument.

But set against this, it is impossible to pretend that Britain’s position in the EU would not change after an ‘in’ vote. Much of our negotiating leverage in Brussels has stemmed from the sense that this country’s Eurosceptic electorate can only be pushed so far. That threat will lose much, if not all, of its force if Britain votes to stay in and essentially ratifies all the ways in which the EU has changed since the last vote in 1975.

This is, perhaps, why so many Tories now wish the referendum were not happening at all. (When I asked a friend of both Osborne and Gove how they could have dinner at Dorneywood after the Saturday cabinet meeting despite being on opposite sides, I was told: ‘This mess isn’t either of their faults.’) It was intended as a way of keeping the party together during the last parliament, and limiting Ukip’s appeal. When Cameron committed to the referendum, it seemed likely that there would be EU treaty change before 2017, which would have given him a stronger negotiating position and may well have triggered his ‘referendum lock’, prompting an in-out vote regardless.

Cameron’s approach to leadership has always been to take decisions then deal with the consequences later. This makes him less prone to the indecision that afflicts so many politicians. And his fluid approach steered him to a second term with a Conservative majority, which seemed a distant prospect at this time last year.

But Cameron’s referendum was a Faustian pact: it got him though the coalition years — but now the price must be paid. His doomsday warnings about what leaving the EU would mean have been undermined by the fact that he offered the referendum in the first place and claimed to have an open mind about the question.

Downing Street is furious that the Queen has ended up embroiled in the EU debate. But this was, perhaps, inevitable after the extent to which it was briefed that Jeremy Heywood, the Cabinet Secretary, and Christopher Geidt, the Queen’s private secretary, had collaborated on the monarch’s intervention days before the 2014 Scottish referendum. (Although the Queen acted at the behest of other members of her family, rather than aides.) When her view, however coded, becomes known on one constitutional question, it is inevitable that journalists will try to find out what she thinks about others. If the Queen is to be truly above politics, then she cannot be selective about it.

The Scottish vote brings up another fascinating question: what will Cameron do if ‘out’ is ahead in the days before 23 June? In Scotland, the Unionist parties responded to a YouGov poll suggesting the Scots would vote for independence with ‘The Vow’, which promised more devolution. Alex Salmond believes this was crucial to his side’s defeat. But given that Cameron has to negotiate any EU deal with every other member, no extra powers can be credibly promised mid-campaign. One thing the government could do, though, is commit to a referendum on Turkish EU member-ship. The rhetoric on Turkish accession has already changed dramatically. George Osborne now emphasises that Britain can veto it and government insiders point out in private that the Greek, Cypriot and French attitudes to Turkey joining mean that it just isn’t going to happen. Sceptical voters may be won over by a promise that they would get a referendum on whether Turkey can join and whether free movement rights are extended to another 75 million people.

This might be the closest Cameron can get to a Scottish-style ‘vow’, a last-minute concession. It would be a volte face: Britain has traditionally been a great enthusiast for Turkish accession. Promising a referendum would alienate a country of great strategic importance. But if the choice were between that and losing the vote, Cameron would not see much of a dilemma.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in