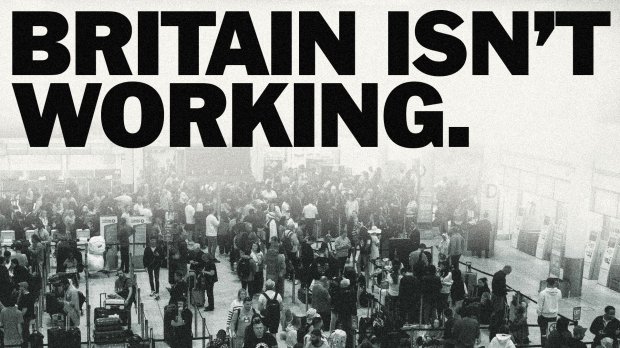

David Cameron’s attempt to renegotiate Britain’s EU membership has served as a powerful reminder of the case for leaving. The EU is designed in such a way that almost no sensible proposal can be passed. If one member state has a good idea, the other 27 members demand a price for approving it, or they demand concessions until it is completely watered down. If the leader of a country protests, the response is clear: What are you going to do? Walk away? You wouldn’t dare.

The EU’s power-mongering has a cost. The euro has hideously distorted the economies of the member states that adopted it, and the abolition of so many border controls has worsened the immigration crisis — which, in much of Europe, has fostered a political crisis. A new banking crisis may be under way, and all the edicts from Brussels about financial regulation will do little to prevent it. What should have been troubling EU leaders at their summit was not just Britain’s possible exit, but the question of whether the union itself will survive.

It is typical of the EU that the summit should get bogged down in finer points of detail without anyone being able to address the bigger picture. We have had hours and hours of debate over how much child benefit should be paid to the family of a Polish parent working in Britain whose children remain back home. Meanwhile, a more fundamental issue has not been addressed: that western Europe’s generous welfare policies are simply never going to be compatible with mass migration, whether from outside or inside the EU. Cameron sees this problem, and was offering a solution: to ban immigrants from all benefits for four years.

As the Prime Minister recognises, it is one thing for a frontier society like 19th-century America to absorb huge numbers of migrants. Americans had no welfare state and a voracious appetite for work. But the situation is very different when it comes to a continent where economic policy revolves around protecting existing jobs rather than creating new ones, and where there are social policies committing governments to high levels of support for the poor. As Sweden and Germany have shown, generous welfare policies and open borders inevitably end in a nasty collision. If you offer cradle-to-grave security and simultaneously invite the world in, you mustn’t be surprised when the world turns up and starts to drain your exchequer faster than your taxpayers can fill it.

David Cameron’s original proposal sent an important message: come to Britain to work, and don’t expect to be eligible for full social benefits until you have been contributing to the tax system for several years. It is a template which the EU should be adopting. This is the way to reconcile free movement of people with generous benefits: restrict their availability to newcomers. The EU’s failure to recognise this demonstrates that it is structurally unable to respond to such upheavals as the migration crisis.

The UK has been a vocal advocate of the ‘four freedoms’ that the EU purports to stand for: free movement of goods, services, workers and capital. The problem is that the EU itself actively opposes free trade, favouring a morally indefensible policy of overt protectionism. Nearly 60 years after it was founded from the European Coal and Steel Community, and more than 20 years after the foundation of the ‘single market’, the EU has made little progress in opening up cross-border trade in services such as banking and insurance. For an economy like Britain’s, which is heavily based on services, this is a serious failing.

Neither has the EU been particularly successful in opening up trade to the rest of the world. It still has no trade treaty with Japan, for instance. We are forever being told by the ‘in’ campaign that we have to be in the EU in order to gain the extra weight that it takes to negotiate international trade deals. Yet independent Switzerland has managed to sort out a treaty with Japan. Why can’t the EU?

The EU’s biggest problem is that its economic and social policies are unsustainable. It is ridiculous that taxpayers must subsidise farmers even when they are producing little food. The euro has been propped up for the time being, but the strain of imposing a single currency and a single interest rate on very different economies will start to tell again soon. As for migration, forget the lofty ideals — just look at what member states are doing: putting up fences as they comprehend the cost of open borders.

David Cameron once promised us a fundamental change in Britain’s relationship with the EU. Some hoped he would be able to reshape the EU as the simple free trade bloc which it should have been all along. But the events of the last few weeks and months have made it clear that fundamental reform is not on offer. The EU has again frustrated Britain.

And many in Brussels will be delighted that it has done so. Some may toast our departure, in the event that we decide to leave. Yet sooner or later the day will come when the EU will be forced to reinvent itself along these lines if it is to survive at all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in