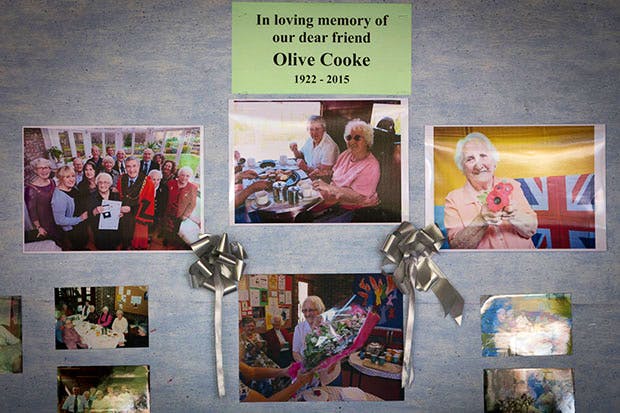

No good deed goes unpunished. This is a saying that applies with special poignancy to Olive Cooke, the 92-year-old poppy seller who jumped to her death in the Avon Gorge near Bristol after receiving something like 3,000 begging letters a year from charities. Mrs Cooke was a great believer in charity. She had sold poppies on behalf of the Royal British Legion since 1938, taking up position every November outside the entrance to Bristol Cathedral. She may have disposed of more than 30,000 poppies during her eight decades of selling them there.

She was, said her family, somebody of an ‘incredibly kind, generous and charitable nature’ who held 27 direct debits to charities. The word got about. Here, obviously, was a sucker. Charities started passing her contact details to each other until she was on the mailing lists of 99 organisations that bombarded her with begging letters. This may not have been the main cause of her suicide, but it nevertheless left her feeling ‘overwhelmed’, ‘upset’ and ‘depressed’, her family said.

The ruthlessness of charities, as recently exposed in the media, is really quite shocking. Not only do they persecute good people like Mrs Cooke; they also employ sleuths to inspect people’s wills for charitable bequests and then chase up the relatives of the dead for payment — behaviour condemned by bereavement counsellors as ‘indefensible’. At the same time, as the Times exposed, more than a thousand charity executives are paid six-figure salaries, and 277 of these more even than the Prime Minister, who earns £142,500 a year. It is hardly surprising that, as William Shawcross, the chairman of the Charity Commission, said, charities are in danger of losing the public’s trust.

The case of Mrs Cooke is extreme, but her treatment reflects a belief shared by all charities, however respectable, that the best people to pursue for money are those that give it away already. The generous are pursued; the miserly are left in peace. You don’t even have to be very generous to suffer. I have one or two small direct debits to charities, but they regularly write to ask me for more. This has the opposite of the desired effect; it makes me want to cancel the direct debits.

I can see that charities have a problem. There is no very nice way of asking for money, but good manners require that warm expressions of gratitude for a donation should be followed by a substantial period of time during which the giver is permitted to feel good about himself before being targeted for more. It should also be required that telephone fundraisers get to the point immediately rather than invent some other pretext for their call. My old college at university sometimes gets a student, normally a female one, to telephone me at home to tell me what an interesting fellow I must be and how sure she is that I would like to know about life in the college today. Minutes of agonising conversation then follow before she reveals the true purpose of her call.

All this makes one sceptical about charitable giving. How much of it goes on salaries to overpaid executives? How much on further fundraising? How much on advertising, newsletters and public relations? And how much on the cause one would like to support? These are questions that one cannot help asking oneself, even though one will never know the answers.

One is usually advised to be wary of giving money to beggars; better to entrust it to a reputable organisation that will spend it wisely on the people that most need it. But I remain to be convinced. Charities realise that it’s more normal in human nature to want to give to an individual than to an amorphous entity, which is why they advertise with, say, a harrowing photograph of a starving child. The person then feels that it’s that specific child he is helping when he gives the charity money. Safer still to give money directly to the person who will benefit from it, even at the risk of being ripped off. You know the beggar may be a fraud, but you also at least know that he will be genuinely grateful.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in