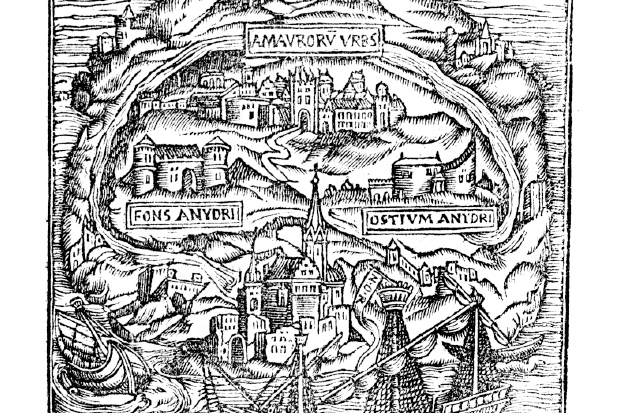

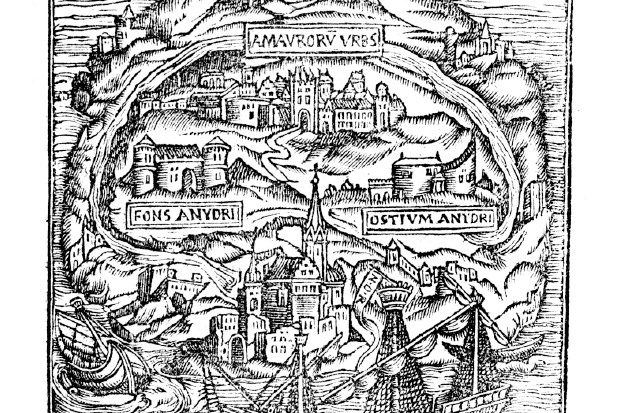

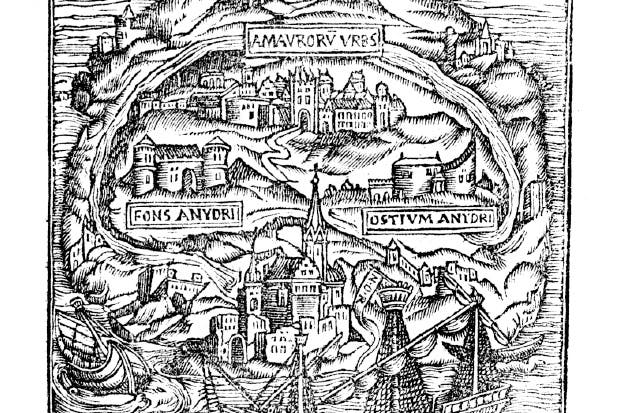

As anniversaries go, the timing could hardly be more apt. As Europe braces itself for the next Islamist attack, the next assault on our civilisation, a season of events marks the 500th birthday of a book that outlined an enlightened vision of the ideal society. Utopia 2016 is a year-long celebration of Thomas More’s Utopia at London’s Somerset House, where the Royal Society and the Royal Academy used to meet.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

Utopia 2016: A Year of Imagination & Possibility is at Somerset House, London WC2, from 25 January.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in