In late Victorian south London a ‘lower-middle-class’ boy, Arthur Ward, is lingering over his copy of The Arabian Nights. The book falls open at a colour illustration of Scheherazade, mysteriously pictured with a white peacock. Twenty years later, she materialises as Kâramanèh, the dazzling female sidekick of Fu Manchu. Young Arthur, who by now had reinvented himself as Sax Rohmer, was the author of the Fu Manchu novels, and Arthur had faded so far into the background that it seems even Sax Rohmer forgot him. He conjured his pen name from the Saxon, ‘Sax’ for ‘blade’ and ‘rohmer’ which means ‘roamer’. He was in essence the original bladerunner. In this enchantingly playful collection of essays on Rohmer the facts of his life are as vaporous as the pea-soupers that informed his imaginings. As Antony Clayton reports, Arthur’s was a ‘strangely neglected childhood’.

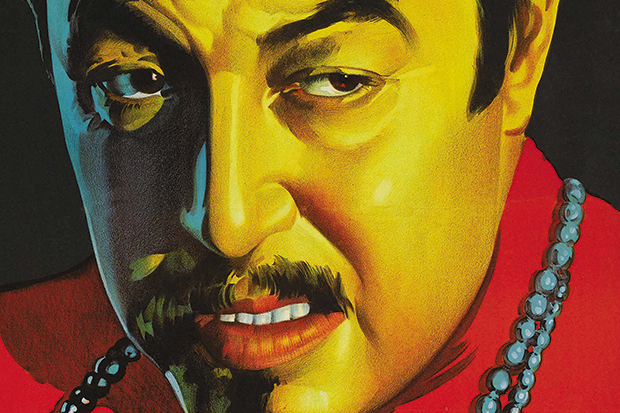

As a songwriter and music-hall sketch writer Rohmer hit the money lode with The Mystery of Doctor Fu-Manchu (1913). The moustachioed super-villain fed the Edwardian appetite for murderous plots involving dacoits and thuggees. He had ‘dragon ladies’ as glamorous assistants. He was an agent of the secret society Si-Fan, and the mastermind behind the assassinations of western imperialists.

In an essay luminous with detail, Ann Witchard describes the sulphurous city in which young Arthur began his plotting, depicted by Whistler swathed in a ghastly yellow, the colour of Wildean decadence. Other essayists provide historical context for Rohmer’s dabblings in the Orient. But what enlivens his fiction is his total disregard for empirical truth. Panics about immigration, a new journalism personified by W. T. Stead, best known for his investigation of child sex trafficking in Lisson Grove, alongside outbreaks of cholera in slums, fed the fears of the reading public. Of all the immigrants, the Chinese were regarded as particularly ‘unassimilable’. Despite the fact that the crime rate actually fell after Chinese families moved into Limehouse, the East End dock became notorious for lurid goings-on. Rohmer took his cue, blending aspects of Egyptomania with Sinophobia for the ‘rot-revellers and tosh-connoisseurs’. For the modern reader, Rohmer offers a ‘luresome’ view of ‘teemful’ early 20th-century London.

Racism is the real scourge of the metro-polis. Phil Baker argues that Rohmer’s ‘opportunistic bigotry’ was more culpable than genuine fear. Witchard says all this fuss about opium and yellow devils was actually Dickens’s fault — Edwin Drood, in particular. But the momentum was in full swing, boosted by a bohemian fascination with intoxication, and the moral majority’s fear of the enemy within.

Enter the Gaiety Girl clad in loose silk robes and warbling against a backdrop of wind chimes. Rohmer based Dope (1919) on the case of Billie Carleton, a starlet who was famously found dead in her Savoy suite the morning after the Armistice night Victory Ball. She had overdosed on drugs supplied by Ada Son Ping Yu, the Scottish wife of a Limehouse Chinese. Another newsworthy fatality involved a nightclub hostess, a stash of cocaine, and a West End playboy known as Brilliant Chang. He became Burma Chang, the evil genius of Rohmer’s Yellow Shadows (1919).

Imperial Gothic, found in writers such as Rider Haggard, and esoteric occultism, with its sinister rites from ‘abroad’, as opposed to a Christianity that could only rustle up a village fête, fed Rohmer’s bank balance throughout his lifetime. But what makes Fu Manchu so beguiling and so long-lived (apart from his elixir of youth, of course)? He is ingenious, agile, a master of disguise. But one of this criminal mastermind’s most distinguishing characteristics is that he keeps his word — the quintessential trait of the English gentleman.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Lilian Pizzichini is the author of Music Night at the Apollo.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in