I was not quite sure whether to be annoyed or relieved about the recent High Court decision not to recognise bridge as a sport. On the one hand, it’s a comfort to know that there is now little danger of British bridge and, pari passu, chess being classified alongside activities that feature perspiring individuals running around in underwear. Chess should, in my opinion, be dignified by elegant surroundings, with the players in formal attire, as in the fictional sequence of the James Bond movie From Russia with Love, or the encounters between Nigel Short and Garry Kasparov that were screened by Channel 4 in 1987.

However, with established chess championships going back for well over 100 years, competitions carried out under strict conditions, a stratified title system, millions in prizes for world matches, and recognition by the International Olympic Committee, I think high-level competitive chess should certainly be granted the status of a mind sport. Indeed, it is a sport where male and female, young and old, even the deaf, blind and physically disabled can compete with equal prospects.

What’s more, chess is recognised as a sport in all the former eastern bloc countries, as well as in China and almost all of the European Union, the exceptions being the UK, the Republic of Ireland, Belgium and Sweden. Sweden plans to rectify this next year. And Russia is trying to have chess included in the Winter Olympics, while chess and bridge have been invited to apply for inclusion in the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

This week’s game was the real-life model for the combination in the fictional game between Kronsteen and McAdams from the film From Russia with Love. Notes are based on those from Spassky Move by Move by Zenon Franco (Everyman Chess).

Spassky-Bronstein: Leningrad 1960; King’s Gambit

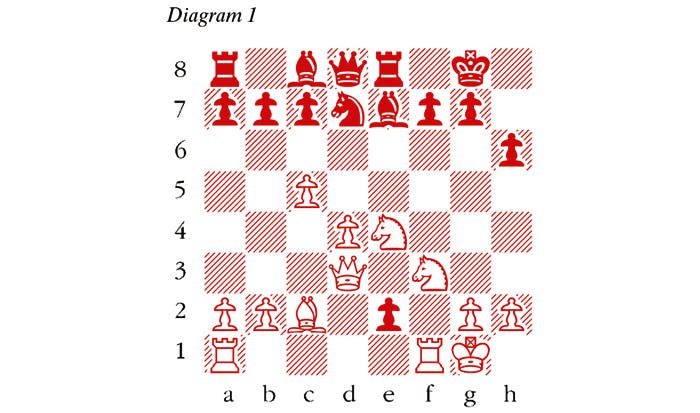

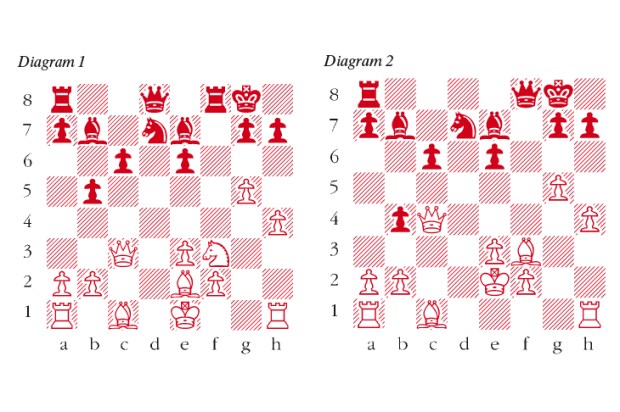

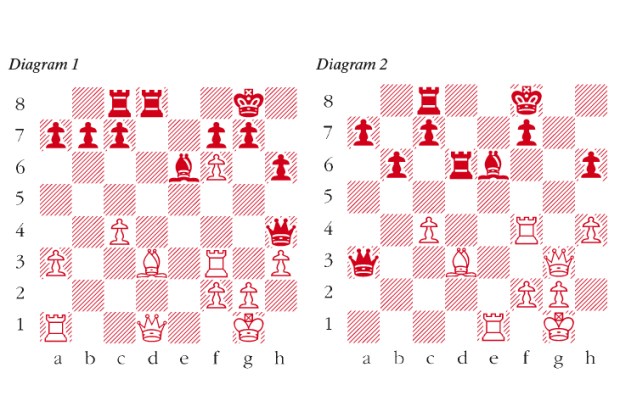

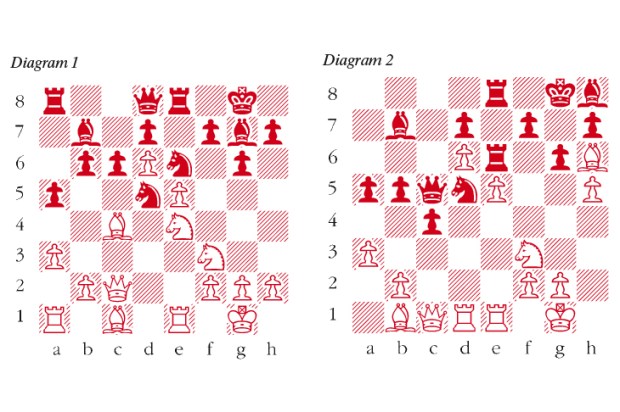

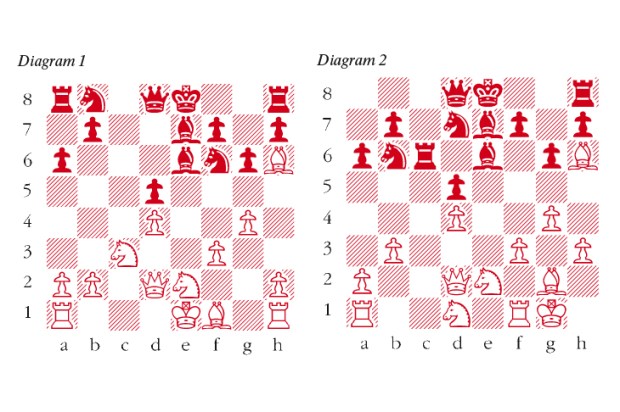

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 d5 4 exd5 Bd6 5 Nc3 Ne7 6 d4 0-0 7 Bd3 Nd7 8 0-0 h6 9 Ne4 White sacrifices his d5-pawn in order to launch a strong offensive. 9 … Nxd5 10 c4 Ne3 11 Bxe3 fxe3 12 c5 Be7 13 Bc2 Spassky wrote that this was the most difficult move of the game. It is sharper than 13 Qe2 Nf6 14 Qxe3 Be6, which leads to a rather unclear position. 13 … Re8 14 Qd3 e2 (see diagram 1) 15 Nd6!! Objectively this is not the best continuation but it is certainly one of the most spectacular moves in the history of chess, and also one of the most surprising decisions, because the quiet 15 Rf2! (or even 15 Qxe2) would have given White the advantage. 15 … Nf8 Black’s had to try the calm 15 … exf1Q+ 16 Rxf1 Bxd6 17 Qh7+ Kf8 18 cxd6 cxd6 19 Qh8+ Ke7 20 Re1+ Ne5! 21 Qxg7 Rg8! 22 Qxh6 Qb6! 23 Kh1 Be6 24 dxe5 with an unclear position. 16 Nxf7 exf1Q+ 17 Rxf1 Despite the fact that Black is a rook ahead and has several pieces close to his king, he cannot defend against White’s domination of the light-squares. If 17 … Qd5 18 Bb3 Qxf7 19 Bxf7+ Kxf7 20 Qc4+ Kg6 21 Qg8 Bf6 22 Nh4+ Bxh4 23 Qf7+ Kh7 24 Qxe8 and wins. Finally 17 … Kxf7 loses to 18 Ne5+ Kg8 19 Qh7+! Nxh7 20 Bb3+ Kh8 21 Ng6++. 17 … Bf5 18 Qxf5 With two pawns for the exchange and an attack on the king, the result is no longer in doubt. 18 … Qd7 19 Qf4 Bf6 20 N3e5 Qe7 21 Bb3 Bxe5 22 Nxe5+ Kh7 23 Qe4+ Black resigns

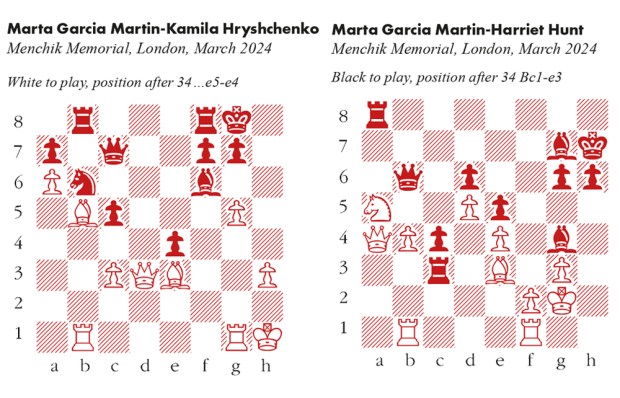

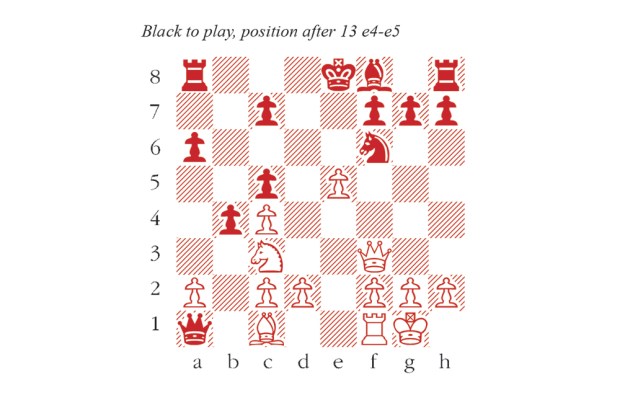

This week’s puzzle is from the women’s grand prix in Monaco, won by Hou Yifan.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in