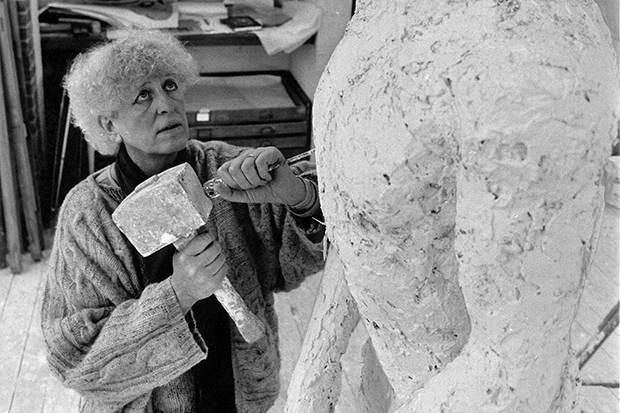

In a converted barn in Dorset, not far from the rural studio where she made many of her greatest sculptures, Elisabeth Frink’s son Lin is showing me his incredible collection of his mother’s work. More than 20 years since his mother died, he’s kept the vast bulk of it together.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in