Brahms’s Clarinet Quintet begins, writes his biographer Jan Swafford, with ‘a gentle, dying-away roulade that raises a veil of autumnal melancholy over the whole piece: the evanescent sweet-sadness of autumn, beautiful in its dying’.

This being late autumn, I listened to the quintet on Sunday to see if its ‘distillation of Brahmsian yearning’ still made an overwhelming impression on me. It did. I swear these are the most miserable 35 minutes in classical music.

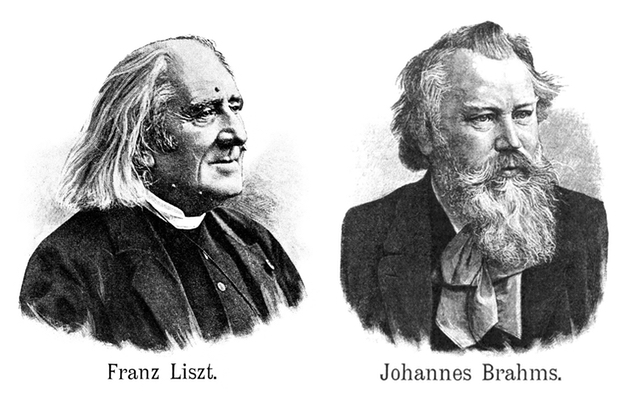

One critic refers admiringly to the display of ‘every super-refined shade of silver-grey regret’. But that’s the problem. The ageing Brahms — obese, cantankerous, his spirits lowered by the deaths of friends and undiagnosed cancer — sets about depressing his audience with the precision of a genius (which he was). No sooner has the clarinet soared than it finds a clever way to snake down the stave, slithering through the elegant droopy twiddling of the strings. Every movement sounds much the same to me, but that’s a heresy that lovers of the work — and they are countless — think they can refute just by pointing at the score, where Brahms tweaks the counterpoint and crops the phrases so that there’s always something new happening.

And so the old boy gets away with forcing his mood on us, whereas when Mahler does it we wince at his self-pity. That’s fine if you’re into the heavy wistfulness of late Brahms chamber music. I loathe it, not just because it strikes me as spiritually empty but because the composer’s superlative craftsmanship ensures that every bar is drenched in despair. Nobody could describe the Clarinet Quintet as an uneven work.

Craftsmanship can be dangerous for musicians. Its relationship to inspiration is complicated. There are composers — Telemann, Rimsky-Korsakov, perhaps Richard Strauss — whose contrapuntal fluency or mastery of the orchestra fails to disguise thin material. There’s the sad case of Mendelssohn, of whom it’s been said that he was born a genius and died a fine composer. He was 16 when he wrote his incomparable Octet, after which his inspiration faded but his technical facility didn’t; the late Violin Concerto marks a return to form, but not to the form of the Octet — to my ears it’s tainted by that close relation of craftsmanship, good taste.

With Brahms, you’re venturing into difficult territory, not least because his devotees think anyone who criticises him must be tone-deaf or a secret fan of Karl Jenkins. They’re ruder in my experience than Wagnerians, who are used to hearing their idol being trashed. They insist that Brahms’s craftsmanship reached wondrous levels but was always at the service of increasingly subtle ideas. Moreover, he was a visionary — Schoenberg, no less, said his asymmetrical phrases made him ‘progressive’.

Maybe so, but it’s not the whole picture. The Second Piano Concerto is certainly innovative (e.g., four movements instead of three) but its close-knit subtlety makes it —heresy alert — more boring than its predecessor. The finale of the Fourth Symphony is a tightly argued passacaglia, a fact that surprises musicologists far more than it does audiences; I listen to it dutifully, whereas the blazing finale of the First has me on the edge of my seat. The craftsmanship of the Fourth never lets up, and the result is a work that — like the Clarinet Quintet — verges on monotony.

There’s a supremely professional evenness about late Brahms that, alas, really is prophetic. The cult of craftsmanship is the curse of modern classical music. Brahms can’t take all the blame for it; 20th-century composers didn’t want to ape his unsexy mannerisms — yet, without realising it, they inherited his cast of mind.

Schoenberg, who thought Brahms was such a pioneer, turned evenness into doctrine with his 12-tone technique. Tonal composers achieved dreary consistency by different means: there are symphonies by Sibelius, Vaughan Williams, Prokofiev, Shostakovich and dozens of lesser contemporaries in which uniformity of style can make you lose track of which movement you’re in. Minimalism? Don’t get me started. And nine out of ten 21st-century chamber and symphonic works are so ‘subtle’, however extreme their dynamics, that they’re unmemorable even if you’ve followed the composer’s conceited programme notes.

It’s at times like this that I yearn for Schumann or early Bruckner, who were so carried away by their ideas that they can sound like self-taught amateurs. They’d never get away with it today. Rough-hewn or untidy music is ‘unprofessional’ and might lose you a commission. And so concertgoers are condemned to yet more intricate ‘soundscapes’ that, for all their craftsmanship, are little more than management jargon set to music.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in